Hillary Clinton might lose the presidency, and even the nomination, because she is a woman. Among Sanders’ fans who support him with militant millennialism, or Trump supporters who talk about women as if they were dogs, this statement will likely be written off. I might be seen as another worried supporter crying sexism to distract from the actual shortcomings and missteps of Clinton’s campaign. But call off the Berniebots and silence the Trumpeters, because I aim not to qualify my decision to vote for Hillary nor to challenge yours not to. Pointing to professional gender norms and the role of sexism in the media, I aim instead to trace Hillary’s backlash to her gender performance, illustrating the double binds that obstruct paths to success by holding professional women at higher standards than their male counterparts.

Performing gender doesn’t happen in a social vacuum. It happens, rather, in a world of social hierarchies and pressures that enforce expectations and consequences of performance. Women and men are held to different standards of self-presentation, with male-associated behavior more suited for professional success. Tyler Okimoto and Victoria Brescoll’s (2010) study of women in power shows that ambitious women tend to engender feelings of anger and contempt from their male counterparts. These feelings likely come from the cultural understanding of women as “communal”- kind, sensitive and caring, and men as “agentic”-aggressive, competitive, and assertive. Women in public leadership positions who exhibit behaviors not traditionally associated with their gender often risk backlash, even if these behaviors are necessary for their job or position. This theory gains credence from a 2008 study in which male and female participants both “assigned less status” to women who exhibited competitiveness, strong leadership styles, authoritative rhetoric, and ambition (note that each of these characteristics are intrinsic to the demeanor of a president).

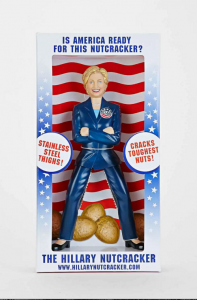

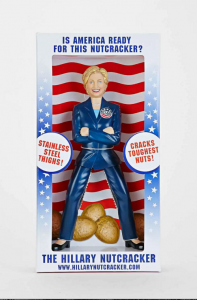

Gendered expectations force women to do intense identity work to prove their qualifications and capabilities both as a woman and as a professional. As a result, women can “easily cross the line and appear to be insufficiently feminine- that is, not “nice” enough” (Carroll 2009, 6). Sociologist Rosabeth Moss Kanter comments on this dynamic in her work on gender and tokenism, laying out four common stereotypes and associated identities forced upon professional women. Three of these four identities are markedly feminine (the seductress, mother, and pet), while one bares masculine undertones (the iron maiden). The latter is implicitly critical, using masculine imagery to shame strong women. This unfairly places women into roles they may or may not identity with, since “women inducted into the iron maiden role are stereotyped as tougher than they are (hence the name) and trapped in a more militant stance than they might otherwise take” (Kanter 984, 1977).

Viewed by many as an iron maiden, Clinton bears harsh attacks for her perceived lack of femininity. As articulated by Diana B. Carlin and Kelly Winfrey, in the 2008 race, “both Clinton’s physical appearance and her choice of pantsuits over skirts and dresses were the source of considerable derision.” Public figures speak often and sharply of Clinton’s appearance. Rush Limbaugh in 2008 contrasted Clinton with Sarah Palin by saying that Clinton is “not going to remind anybody of their ex-wife, she’s going to remind men, ‘Gee, I wish she was single’’ (Carlin and Winfrey 2009, 331, 338). The double standard therefore extends to the media by creating a platform to judge men on a basis of merit while women, as illustrated by Limbaugh’s statement, are judged by personality, physical attractiveness, and gender performance. FOX news contributor Tucker Carlson once said of Hillary: “when she comes on television, I involuntarily cross my legs.” This statement directly paints Clinton as a danger to men everywhere, reinforcing the harmful characterization of powerful women as threats to male-dominated institutions.

Journalists bear equal blame for negatively reporting on Clinton’s gender performance. Prominent amongst these pen-yielding mudslingers is New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, whose scathing columns boil to the brim with sexist sentiment. In a 2015 column, Dowd described Clinton as a “granny” who should learn to “campaign as a woman.” Dowd, who once called Clinton “the manliest candidate,” later criticized her as over-feminizing, stating that she “should have run as a man this time.” From these wildly offensive (and contradictory) statements to the claim the Hillary “killed feminism,” Dowd and reporters like her use Hillary’s sex as a weapon of slander and hate, harming public perception by shaming her non-hegemonic gender performance.

Some media sexism comes in abrasive and obvious forms, like calling Hillary “shrill” or “bitchy,” but the majority of it comes by subtly addressing female candidates with less respect than their male opponents. As discovered in Joseph Uscinski and Lilly Goren’s 2010 study of the 2008 Democratic Primary, both sexes tend to call men by their titles and women by their first names. In the 2008 primaries, Clinton was referenced in newspaper coverage “by first name 3 percent more [than opponent Barack Obama) and her title of Senator was omitted 15 percent more.” On television, Clinton was referenced by first name four times more than Obama was. These seemingly minute and peripheral statistics actually resonate deeply within the dynamics of a campaign. As Uscinsi and Goren (2010) found, “referencing a woman by a first name may project an image of inferiority to the audience.” The media therefore disadvantages Clinton not only through overt sexism, but by subtly painting her as a less viable candidate.

Hillary Clinton is, and always has been, a polarizing figure. Her long career of spotlight scrutiny left her seasoned with scars, dividing the American public sharply between champions and critics. As a fellow on Clinton’s campaign who spent months canvassing door-to-door, I heard time and time again that people like her policies but not her personality, her vision but not her voice, her ideas but not her identity. These criticisms come largely from those who see Hillary as a threat to hegemonic gender norms, and who watch, unsettled, as she every day cuts cracks in the glass ceiling not with a stiletto or kitchen knife, but with her own two hands. We need to stop pretending that the playing field is level. Like it or not, Hillary Clinton is not a man. She’s a woman (a strong woman), and it’s time we stopped punishing her for it.