It’s no secret that feelings of oppression and exclusion on the basis of race have been manifesting themselves in unprecedented ways across the country. The other day I came across a post in the Columbia University Class of 2018 Facebook group that did not receive national attention, but perhaps warranted the attention because the way in which it represented conversations about racial relations within the US. The issue began when a student of color asked her class’s Facebook group if anyone knew of any Contemporary Civilization sections that were taught by a professor of color. After receiving no help, the student specifically asked if any white students wanted to give up their seat in a section taught by professor of color:

The post sparked a heated discussion about the student of color’s right to be taught by professor of color and the role white students should play in responding to requests like this.

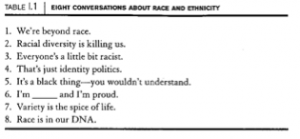

In the book Doing Race by Hazel Markus and Paula Moya, the two authors assert that conversations like these about race and ethnicity can be divided into eight themes:

Among the eight different way of talking about race, there are two racial schemas that are particularly prominent in this Facebook post and the subsequent discussion. The first of the two viewpoints, “that’s just identity politics,” is predicated on the idea that race and ethnicity are “irrelevant to, or a distraction from” more important universal concerns. Those who share this opinion often express frustration that those who “have” race or ethnicity receive special privileges that are unfairly denied to those who do not.

The first student to respond to the post expressed these sentiments when he argued that such a request was symptomatic of a sense of entitlement and added that it was an “unnecessary step to specifically call on white people.” Other students questioned the importance of sharing an identity with one’s professor: “Could someone please explain to me why it’s acceptable to refuse to be taught by a highly educated, highly trained professor because they’re white?” Yet another student expanded upon this argument by asserting that a professor’s pigment does not define their teaching methods, subjects of interest, or their beliefs. Therefore these students suggested that grouping professors of color into one category seems racist. This student was essentially making a cry of “reverse racism.” Doing so disregards the systems of racial disadvantages that permeate higher education and therefore such a request is inherently not racist. Instead, what the student of color was seeking was a professor likely to be more sensitive to how white scholars’ perspectives shape interpretations of Classic Civilizations.

A student responding to these two comments vehemently disagreed with assertion that being able to identify with a professor does little or next to nothing for a student. She asserted, “this is easy for you to say when America looks at you, affirms your humanity, and teaches you your experiences are normative, while those of others are deviant from it and their own faults.” She then added that many of the texts in the class inspired the racism that her and other students of color were forced to deal with daily. Therefore, having a professor with a deeper and more personal understanding of what these documents mean for people of color can be an invaluable experience for students of color.

This school of thought falls under the category of “It’s a black thing – you wouldn’t understand” in Doing Race. The main idea behind this viewpoint is that, as a result of one’s racial identity, one’s life is so different that it cannot be completely understood by others who do not have such identity-related experiences.

Although it is not fair to expect minority students to explain their points of view to white students whose experiences are better integrated into the educational institutions they are a part of, it is important to analyze and unpack dialogues like this. In the conclusion of their essay on “Doing Race,” authors Paula Moya and Hazel Rose Markus assert that though “it may not be easy, and it may not be total, humans are able to communicate across [their] differences.” Though often times, ignorance and a lack of desire to find a middle ground precludes this possibility, this assertion certainly can be true. As a white male, I cannot reasonably say that my review of this incident has made it entirely clear to me what this student of color is going through. However, I can say reading the conversation and thinking about all the systems of power that underlie it, shed a great deal of light on the issues for me. I am now more understanding of the request and more sympathetic towards students who are forced to learn about sensitive historical topics from someone whose own struggles are quite different from their own.