In class this week, we looked at different covers for a work– The Iliad, in this case– and speculated on what the different choices chose to emphasize about the work they were representing to the reader. This got me thinking about the different people such paratext serves.

The first party the paratext can serve is the author. If a cover gives a reader or buyer an accurate reflection of the author’s vision, then I’d say it’s furthering their artistic expression by spreading it, (illuminating it, even) and hopefully appealing to the kinds of people who they hope will experience their work. Today, authors don’t usually have a hand in the paratext of their book, so this end isn’t always served at all.

Publishers are in charge of making as much of a profit as possible, and they choose whatever images and text appear on the cover. Their goal is not to highlight the author’s intent, but to make the contents marketable. I’m not saying it doesn’t still serve the author by getting their work to as many people as possible, but even if the resulting paratext is what the author would have chosen, it was arrived at by a different intent.

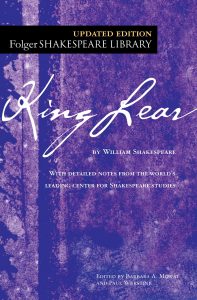

Finally, the paratext serves the reader by coloring their opinion of the work. It helps us choose what we want to read, of course, but it also gives us a sense to view the work through once we’ve begun. I think of the difference between the copies of a book my high school had, for example, vs. the one I might find at a book store. I’ll use King Lear as an example, just because I remember the edition I read in high school as stunningly nondescript:

There it is. Other than the title, it tells us nothing. If anything, I would say it tells us that this is going to be a pretty dry read, in a pretty dry, academic setting. This may as well be the cover of a computer science textbook. The designer of this school edition, I’d assume, knew that they didn’t need to market this to the public: they just needed a cheap cover for a volume that schools would buy in bulk and that students would read whether they liked it or not. So I think that’s the opinion most high school students have of King Lear. It was boring, and they had to read it for class.

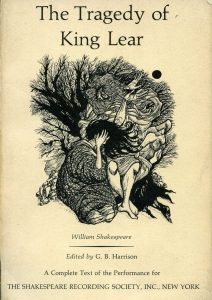

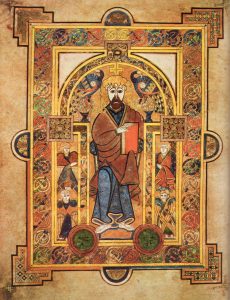

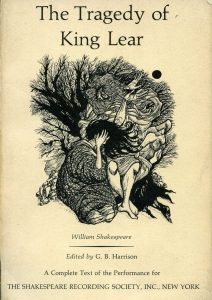

In contrast, take this one:

This draws a much more intriguing picture. It tells us that it’s a tragic story, for one thing. The style of the artwork reminds me of medieval art, but I don’t think it is. I think it’s implying that the story takes place in the distant past. I can even extrapolate that there’s an old man who suffers, and causes others to suffer too, based on the figures. At the very least, I could conceivably be intrigued by what’s inside. It’s an interesting enough story to have an interesting cover, and I might approach it differently as a reader if that was my first impression of it.

So I guess paratext serves the company first and the author last, while the reader either is or isn’t depending on the publisher’s approach. What do you guys think?