A letter doesn’t communicate by words alone. A letter, just like a book, can be read by smelling it, touching it and fondling it. Thereby, intelligent folk will say, “Go on then, read what the letter tells you!” whereas the dull-witted will say, “Go on then, read what he’s written!”

– My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk (p. 37)

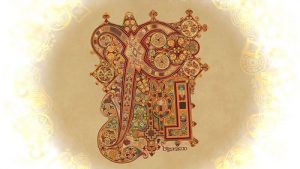

For many of us, illiteracy is often associated with a lack of intelligence. From an early age we are preached about the importance of reading and writing, and how reading and writing are tools that help us grow and better understand the world. However, from the very first day of class this “truth” has been questioned. For example, when “reading” The Book of Hours we rely not on words, but on pictures to understand a story. As I flipped through the book’s images, I often found myself struggling to understand the story being told. I felt handicapped without words to help guide me. My inability to understand a story got me thinking about a different kind of illiteracy – I am “ilvisual” if you will. My difficulty with interpretation does not mean that I am unintelligent. Instead, my difficulty to interpret certain pictures in The Book of Hours speaks to my educational background. My education has emphasized words over image. The opposite appears to be true for the original readers of The Book of Hours. Image was valued over text. Though I may be more skilled at reading, the original readers were more skilled at visual translation.

I came across a passage while reading My Name is Red (written above) that I think speaks to the debate of what it means to be intelligent. According to My Name is Red, I am dull-witted. I must learn to look beyond words. Words are easy. What is written is all you get and what you get is accepted as fact. But with a picture, I need to look for details and symbols that reveal the story. Reading pictures requires more effort than reading a text, and with more effort I believe the story becomes more meaningful.