I went over to the Kennedy Center after class to look at everyone’s collaborative visual narratives, and was amazed at how beautiful they turned out. Will and I are not the most artistic pair, so looking at all the others really amazed me. I especially liked the Orhan Pamuk ones because Will and I thought Don Quixote would be easier for us to illustrate, so tackling that task was very impressive. It was also nice to see what classmates created for Don Quixote, to compare symbolism and see what messages people grasped the most.

“The Fatal Lozenge” : Alphabetizing Sin, Understanding Irrevocable Acts

“The Fatal Lozenge” is a dark alphabet that chronicles twenty-six different figures committing grave, largely irreversible sins. The characters that meet their doom down the alphabet are by turns ignorant and helpless. Gorey scratches at the surface of acts that are not entirely unconscious, but certainly rooted in hardwired impulses.

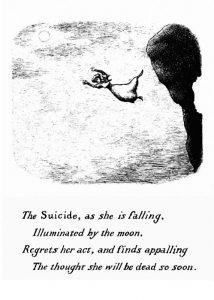

Like we discussed in class, the story seems to offer a comment on natural sin. Though some of the examples in this story are explicit instances of “sin” or even crimes, enacted, there is a psychological root to other examples. People driven to suicide give in to the psychosis of severe depression in any attempt to end their lives. Soldiers (the Zouave) returning from war wrestle with residual violent impulses because of PTSD. Though this is definitely a story about sin, Gorey doesn’t seem to place a heavy-handed blame on every character for the situations they end up in. He intermingles figures acting and being acted upon: the uncle who beats his young nieces and nephews versus the orphan child who perishes in the street. Yet the most troubling examples are those figures who meet failure or doom by their own design, yet as a result of [psychic] forces somewhat beyond their control. I was particularly struck by:

“The Suicide as she is falling/ Illuminated by the moon/ Regrets her act”

Gorey is circling back to acts of impulse and ignorance here, reminding us that they are irrevocable, and often, not without dire consequence. This moment reminded me that despite the macabre trappings of Gorey’s work, he taps into issues that are quite universal, or at least accessible. Statistically, most people who attempt suicide and survive admit that they did indeed instantly regret this act of seeking death. The Wanton, in making herself up with “dangerous” kohl, gives in to not only individual impulse, but also societal pressure for women to achieve beauty through artificial means. The Invalid suffers further because of the mystery of illness, and also because of the failures of his doctors: he is acted upon.

The common thread between every image in this story is the irrevocable nature of each act depicted. The Zouave, conditioned for war, stabs the baby because violence is second nature, and in a single motion, he becomes a child murderer. The suicide gives in to a psychological state that tells her death will relieve the pain of her existence, recovering her will to live only in the moment of limbo before fatal impact. Gorey strikes no middle ground-he draws these figures either right before or right after each one meets his doom or commits his crime. No fates can be reversed in the world or mistakes undone he has created, and though “The Fatal Lozenge” is full of hyperbolic examples, this seems a lesson worth holding on to. A hardened and moderated version of “think before you speak,” Gorey, in a most grim manner, is counseling the reader (supposedly, the child), to also think before acting.

Amphigorey

I thoroughly enjoyed the work of Edward Gorey’s that we looked at in class this week. I found the way that he juxtaposes such morbidity with playful verse and rhymes to be incredibly interesting. The artwork is stunning and the collection of verses that go along with the images in many ways add depth and perspective. His twisted and creepy sense of humor is right up my alley, and while I understand that it isn’t for everyone, I’m sure anyone that reads it can at the very least appreciate the way he addresses such dark and morbid topics while maintaining a comical undertone.

Reading it made me analyze more intensely the ways in which children’s books address topics such as death. Books such as Goodnight Mister Tom or Goodbye Mog often times introduce children to the concepts of death, and helps them begin to internalize the fragility of life, and the implications that death carries for the living. I would imagine tackling such subjects with children is difficult, as the questions would be boundless and the concepts would almost certainly not be grasped immediately, but it’s interesting to think about how literature assists in the process of helping children learn about such things.

Gorey certainly chose to take a different creative direction than the authors of the books mentioned above, as he deals with the topic in a more direct and brutal way. The way that he illustrates and writes about the gruesome ends that children meet, or the way in which he speaks about race and murder probably aren’t what most parents are looking for their kids to read. The stories are inherently dark and quite funny (in my opinion at least), but Gorey addresses head on the dark reality that exists beyond the pages, outside of the book. It certainly isn’t a collection of stories I’d recommend for children, as it deals with issues in much more direct and brutal manner than other literature does.

A Gorey Kind of Funny

While reading through Edward Gorey’s “Amphigorey”, I found that most of the stories were characterized by either gloomy subject matter or satirical commentary. What results from this, I think, is the communication of frequently used story lines and narratives in a completely new form and sometimes, with a dissimilar ending. For example, the Bug Book tells a story dominated by social stratification of groups with the exclusion of those who do not conform. But instead of ending the story with this morality or somehow allowing justice to be had for the ostracized bug, the story ends with the it being killed by the others. Consequently, they are able to continue acting the way they do at the expense of and with the exclusion of others. This is also displayed in the alphabet section entitled, “The Gashlycrumb Tinies” , which categorizes each letter by something somber in nature. One example is, “C is for Clara who wasted away”, another one being, “I is for Ida who drowned in a lake”. Gorey uses format of a child’s learning tool – the alphabet, the very basis of our language – and characterizes it by different forms of death. What are the implications of this choice? Is this simply a stylistic choice, or is Gorey trying to communicate something specific to the reader?

Ghastlycrumb Tinies and Postmortem Photography

I’d read Gorey’s The Ghastlycrumb Tinies before– I knew a girl in elementary school who used to recite it a lot too, how’d you like to be her first grade teacher– but I’d never been able to put a really solid meaning behind. I felt compelled to either understand it as a statement or accept it as just a kind of morbid nursery-rhyme wordplay, and I always chose the second one, because it was just easier that way.

Our discussion in class has helped me put a meaning to it, though, and now I can actually say I like it. It really works for me as a story of neglect, of children left alone to tragic ends. To take this a step further, I like the thought of it as a memorial. So much of Gorey’s style is in homage to the Victorian era, which was one of grimness and high mortality as much, maybe more, as it was one of formality and grandeur. It was the era of post-mortem photography, particularly of children, which the illustrations here remind me a bit of. I won’t put any in this post, because they are disturbing and sensitive things, but I’ve seen some before in museums and I think they share a sense of memoriam, not to mention an astonishing morbidity. Most of the illustrations are, of course, slightly pre-mortem. But the whole goal of photographs like that anyway are to remember the child as they were, in an era where that could likely be the only image of them ever captured.

I’m not denying the elements of humor, obviously. But I think the work can also stand as as an homage to the neglected children of history, especially in the dark and newly-industrialized landscape of Victorian times that Gorey so often portrays the melodrama and tragedy of.

The Scary Children’s Book

The other day in class, we were discussing the differences between the story and the illustration in Edward Gorey’s short stories. I could not help but recount famous stories that we have heard throughout our childhood that had much darker meanings than we associate the childish images with. Looking at the images within Gorey’s book, his playful use of color and animation with his cartoonish drawings offer a sense of childish play in his illustrations. However, further reading of his witty and short writing, open up a whole new world of darkness that we wouldn’t necessarily associate with our version of the modern day children’s books.

As a child I grew up in the magical world of Disney, and it’s princesses and cartoons. Even though I am now 21, I still am obsessed with this portion of my childhood, and can recount any Disney song (with my 24 year-old sister for backup) at any moment. However, what is often ignored is the darker origins of these stories that we hold near and dear to our hearts.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is the first Disney princess classic, and the movie was released in 1937. What is forgotten, is that the origin of this story comes from the 1812 publication of folk tales by the Brothers Grimm. These were fairy tales that had been told for centuries, and they do not fit the definition of “fairy tale” as we know it today. The Evil Queen sends a hunter to kill the fair Snow White, and he can’t so he brings back parts of a dead bear in order to “prove” he had killed her. The Queen then eats these in order to be the fairest of them all. (This part is definitely not included in the Disney version. Finally the story ends at wedding where the Queen is forced to wear burning-hot iron shoes until she drops dead. (Also excluded from the cartoon magical fairy tale by Disney).¹

Snow White is not the only example of this: in Pinocchio Jiminy is killed by Pinocchio and in the Little Mermaid Ariel is killed if she cannot get true love’s kiss. Disney managed to take these dark and intricate stories and turn them into these fabulously bright and happy cartoons kids have been watching for decades. So who knows, maybe in a few years well be watching the newest Disney installment of Gorey’s short stories. It is true that our modern version of the children’s book is very different than the fairytales of the past, and maybe that is what Gorey was inspired by in his stories.

(I had some interesting illustrations of the Brothers Grimm versions of the stories, but I was not allowed to upload them for some reason so if you’re interested just google the stories with Brother’s Grimm!)

- Triska, Zoë. “The REAL Stories Behind These Disney Movies Will Ruin Your Childhood.” The Huffington Post. November 12, 2013. Accessed April 05, 2017. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/11/12/the-real-story-behind-eve_n_4239730.html.

Comments on The Gashlycrumb Tinies

The first thing I find interesting is about the use of times. The ‘tinies’ are all experiencing near-death, but Edward Gorey uses past times to suggest that, they would not be rescued and that they are meant to die. Also, in some of the 26-letter story, the children are not dying, but seem to play for fun without the illustration of the texts below, but for others, it is clear that, they are died in a tragic way.

I think, the use of 26 letters symbols the situation of the whole society which includes everyone. The names after each letter further support his idea. Also, the magic of this story is that, without the texts below, the image cannot be fully understood. For example, for letter Y, it says, ‘Y is for Yorick whose head was knocked in.’ The question raised here is who knocks Yorick in and where, because in this image, it is only Yorick standing in front of the wooden-like cylinder, constantly starring at it with curiosity. I guess Gorey here wants to illustrate something that is between children’s book and the adult’s book. Because when it is children who are reading this, they only look at the image, but for adults, because we are always told to read and analysis in class, we will look at the texts first. This difference gives children and adults a completely opposite view of this single image.

One last thing about his story is that, the children only contain one really tiny part of each image, which sends the messages that, humans are only small parts of the world, but they think of themselves as the ruler. And this is an obvious difference from Gorey’s work and typical children’s books– children’s books are all about the characters’ stories, but Gorey’s work is about the environment that contains the characters.

Gorey- The Vinegar Works

The cover page for The Vinegar Works says that the stories contained inside are “Three Volumes of Moral Instruction”. When thinking about children’s books, many stories have a moral and aim to teach children a specific life lesson. Usually, these morals are constructive, such as the one found at the end of The Tortoise and the Hare or The Boy Who Cried Wolf. In The Gashlycrumb Tinies, instead of outlining a story and ending with a lesson, Gorey goes through the alphabet and describes how different children died. While one could argue that children need to be aware of dangerous objects in the environment, people generally do not alert children to these dangers by describing how deadly they are. Instead of giving a gentle warning, Gorey uses the worst case scenario of death as a guide for what can happen to unsuspecting children.

The Insect God plays with the idea of child abduction and although it isn’t a story that is necessarily fit to read to children, it does address a topic that is often discussed with children. Children are taught from an early age not to get into the car of a stranger. In the story, young Millicent makes this mistake and ends up being sacrificed by insects. This story follows the more traditional outline used to teach children lessons, but it does so in a very dark manner.

Nationality Confusion

Throughout are entire section on Gorey, a question stayed stuck in the back of my mind: why did he insist on making his stories so British?

Yes, I understand that Gorey is attempting to evoke the Victorian Gothic, but why not do so with an American lens?

Was anyone else a little frustrated by the little ploy Gorey was trying to play? Anyone else feel a little slighted by Gorey’s attempt to be British? Or was that only me?

When you think to some of the greatest examples of children’s literature, so many of them are written by British authors. Peter Pan, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Winnie the Pooh, The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe etc. etc. Is this why Gorey wanted to give his books a British flavor?

For me, my frustration stems from the fact that I want Gorey to be understood as one of the great American authors of the children’s genre, and I’m afraid because of his British language and themes, that will not be so.

The Purpose of Illustration

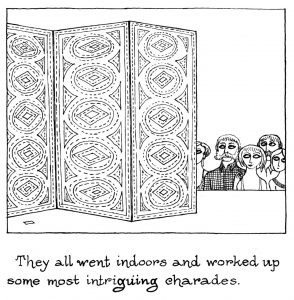

I usually think of illustrations in books as meant to depict the action in the story through a visual representation of what is being read. They add to the story by showing the reader exactly what the words on the page are describing. However, Edward Gorey subverts this convention through The Curious Sofa.

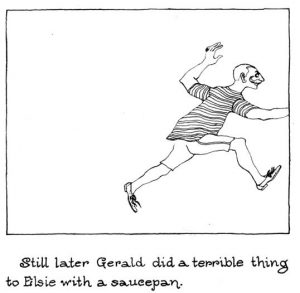

Rather than having his pictures show what the sentences underneath describe, he leaves the main action hidden from the reader, only accessible to the characters themselves. For example, the guests in the picture above get to see what is being acted out in charades while we do not.

Gorey further makes clear his deliberate severance of the reader from the action with panels like the one above, which shows Gerald cut off from our view with part of his arm outside the frame and Elsie not visible at all. What do you think Gorey’s intention is in using his illustrations to cut the reader off from the action rather than to give a clearer picture of what is going on? Is he trying to leave more room for the imagination or is there another explanation?