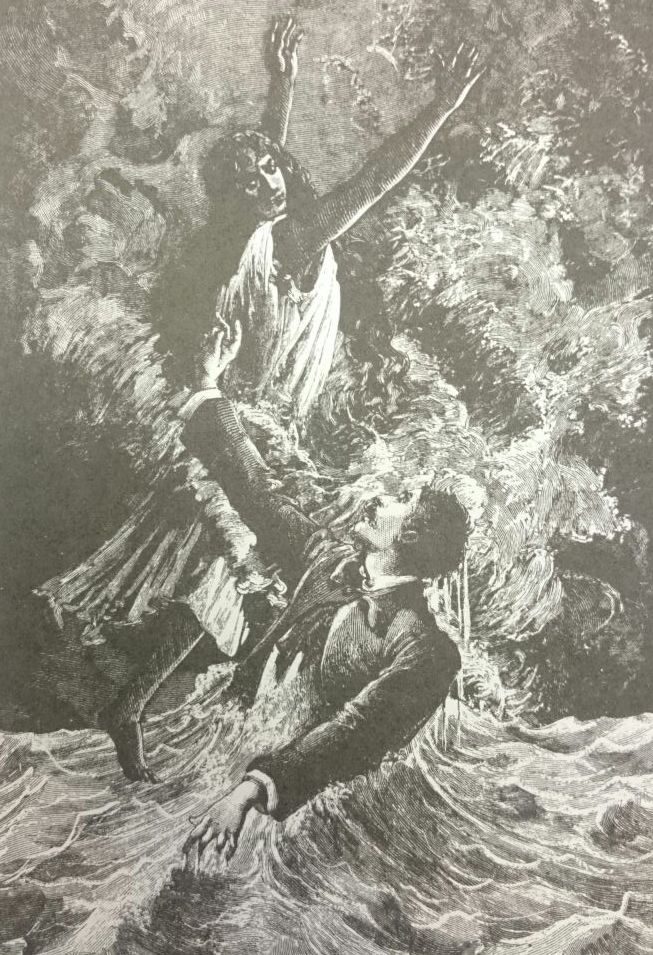

Une Semaine de Bonté… It’s taken me a long while to decide what to blog about this week because of the question mark that is this book by Max Ernst (if it should even be considered a book?).

As a kid, I always gravitated towards darker stories, ones with black and white illustrations and not so friendly looking faces (think Stories to Tell in the Dark and The Series of Unfortunate Events). If I were to lump Une Semaine de Bonté into a category, I would lump it with what I like to call my “creepy books meant for kids.” However, I doubt Ernst had children in mind when he created his five part collection.

So with that I ask my main question, the theme of this blog post: could Une Semaine de Bonté be read by children?

My answer (and I’d love to hear yours too… whether you agree or disagree) is yes. I’ll even go further: I believe this book would be even better in the mind of a child.

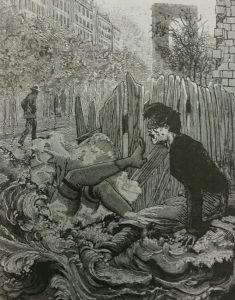

Let me explain. When I first starting flipping through Une Semaine de Bonté, before we got any background information from class, I had no clue what was going on. I concluded that this book was simply a collection of dark collages representing nightmares. No overarching story, just pictures of the same theme. In no way would I have been able to understand that the figures in the pictures were recurring figures. I never would have guessed that each day had a protagonist. Yes, there was a man who always had some sort of mammal for a head, but how was I to know that this mammal-headed human was the same person throughout?

As an adult reader, I have enough knowledge to discern one animal print from another. My ability to distinguish between to images of animals is something learned. However, I believe that a child, someone younger who maybe is not as well trained at distinguishing the different details between mammal-headed figures, would see the mammal-human as the same character. If that person has an animal head, whether it be a bear or a lion or a cat, it must be the same character.

As we age, we lose our sense of imagination and grow more and more logical. It is hard to except these strange images and connect them into a coherent story. But a child, I think would be able to come up with connecting dots to make the seemingly disconnected images of Une Semaine de Bonte whole.