My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk is definitely a challenging read. It is a book that requires the reader to critically think throughout. With all of the different characters that tell their story, it can be difficult to know when to take the words in the book literally, and when to use critical thinking to make sense of the story.

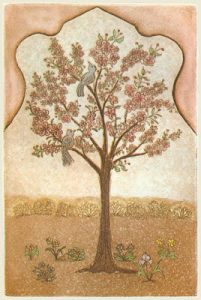

The chapter “I am a Tree,” requires the reader to think a little harder to understand what is going on. I had many questions at the beginning of the chapter. Why does a tree have a chapter to itself? How can a tree even speak? What is the importance of this tree to the story as a whole? It seemed like a completely random decision by Pamuk, but the more I am reading, the more I am realizing how deliberate Pamuk is with every word choice he makes in this book. I became aware of the connection of the tree to the book in the very last paragraph of the chapter.

“I the humble tree before you, have not been drawn with such intent. And not because I fear that if I’d been thus depicted all the dogs in Istanbul would assume I was a real tree and piss on me: I don’t want to be a tree, I want to be its meaning.” (Pamuk, 51)

After reading this, I realized that that tree was a picture all along. This explains why it belongs in a book about illuminations. The tree had actually simultaneously given the perfect description as well as an example of a meta picture, which is a picture about itself.

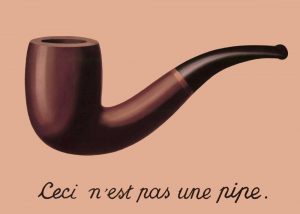

This reminded me of the image above. The caption translates to, “This is not a pipe.” Scott McCloud explained in his book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art that the image means to say that is a picture of a pipe and not a real, tangible pipe itself. Yet another meta picture.