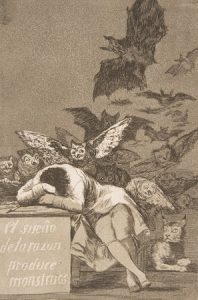

“The Fatal Lozenge” is a dark alphabet that chronicles twenty-six different figures committing grave, largely irreversible sins. The characters that meet their doom down the alphabet are by turns ignorant and helpless. Gorey scratches at the surface of acts that are not entirely unconscious, but certainly rooted in hardwired impulses.

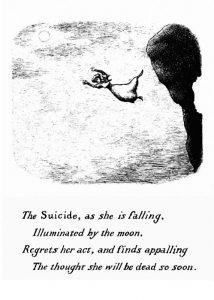

Like we discussed in class, the story seems to offer a comment on natural sin. Though some of the examples in this story are explicit instances of “sin” or even crimes, enacted, there is a psychological root to other examples. People driven to suicide give in to the psychosis of severe depression in any attempt to end their lives. Soldiers (the Zouave) returning from war wrestle with residual violent impulses because of PTSD. Though this is definitely a story about sin, Gorey doesn’t seem to place a heavy-handed blame on every character for the situations they end up in. He intermingles figures acting and being acted upon: the uncle who beats his young nieces and nephews versus the orphan child who perishes in the street. Yet the most troubling examples are those figures who meet failure or doom by their own design, yet as a result of [psychic] forces somewhat beyond their control. I was particularly struck by:

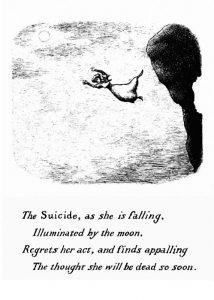

“The Suicide as she is falling/ Illuminated by the moon/ Regrets her act”

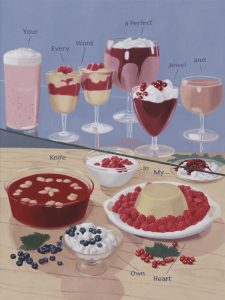

Gorey is circling back to acts of impulse and ignorance here, reminding us that they are irrevocable, and often, not without dire consequence. This moment reminded me that despite the macabre trappings of Gorey’s work, he taps into issues that are quite universal, or at least accessible. Statistically, most people who attempt suicide and survive admit that they did indeed instantly regret this act of seeking death. The Wanton, in making herself up with “dangerous” kohl, gives in to not only individual impulse, but also societal pressure for women to achieve beauty through artificial means. The Invalid suffers further because of the mystery of illness, and also because of the failures of his doctors: he is acted upon.

The common thread between every image in this story is the irrevocable nature of each act depicted. The Zouave, conditioned for war, stabs the baby because violence is second nature, and in a single motion, he becomes a child murderer. The suicide gives in to a psychological state that tells her death will relieve the pain of her existence, recovering her will to live only in the moment of limbo before fatal impact. Gorey strikes no middle ground-he draws these figures either right before or right after each one meets his doom or commits his crime. No fates can be reversed in the world or mistakes undone he has created, and though “The Fatal Lozenge” is full of hyperbolic examples, this seems a lesson worth holding on to. A hardened and moderated version of “think before you speak,” Gorey, in a most grim manner, is counseling the reader (supposedly, the child), to also think before acting.