“I don’t want to be a tree, I want to be its meaning.” – I Am A Tree, p. 51

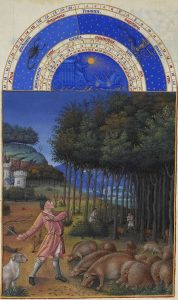

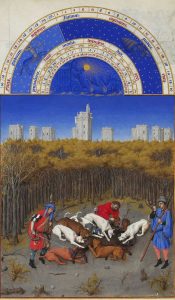

This chapter is written from the perspective of a tree, which was drawn on a sheet of paper that was meant to be included in a manuscript, but never made it into the final product. Immediately before this quote, the narrative voice of the tree states that they are glad they are not drawn in the new style, in which a tree would be drawn in such detail that anyone looking at the picture could select that particular tree out of all the trees in a forest.

This quote leads me to question how it is possible to depict the meaning of a tree. Can the meaning of a tree be conveyed without drawing the tree in great detail? When creating an illumination, an artist strives to uncover the meaning of a scene or object. But as the audience views the illumination, they are left with their interpretation of what they see. The meaning of the tree will first be filtered through the mind of the artist and then through the mind of the audience.

This quote, when taken with the text before it, seems to suggest that the new style of of painting involves the addition of great detail, but the loss of the meaning behind the painting. This thought was counterintuitive to me, because I would normally think that the addition of detail expresses the meaning of an illumination more fully. Perhaps this tree was meant to be a symbol of something greater and by adding detail to the tree, the audience is distracted from that symbolism.