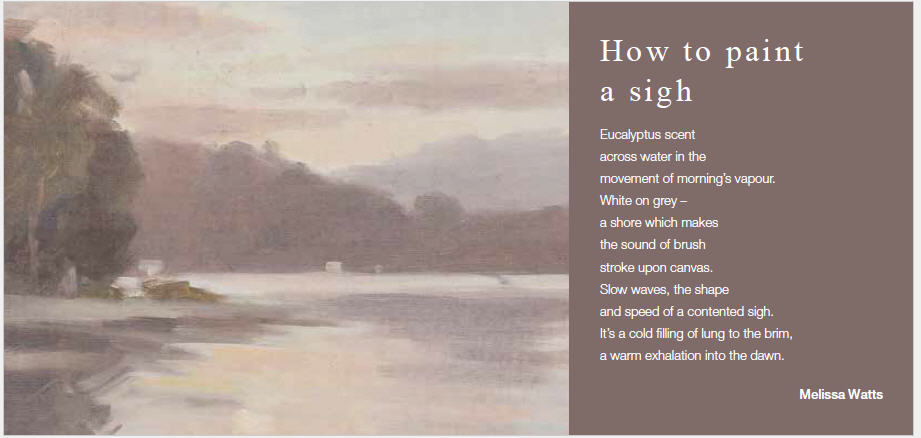

If nonfiction is considered a genre of “truth,” how do these authors understand and approach the issue of paratext when their works are published? Paratext sets the authors at a disadvantage, placing the interpretation of their words one step further beyond their control. And in particular with nonfiction, I wonder if the danger of including some elements of paratext, particularly cover art. The truth and meaning of the text belongs, in disparate moments, to the author, and to each reader. Yet the design of any book cover inevitably influences the reader’s understanding—you see before you read.

Joan Didion, one of my favorite authors, is something of an icon in the writing world. At once, a widespread reverence for her talent as a prose writer has given way in recent years to a commercialization of her image and brand. Her crisp taste, her minimalist aesthetic, and ability to simultaneously reflect upon and dismiss the blundesr of her youth are the envy of many a twenty something woman today. The cover of The Everyman’s Library anthology of Joan Didion’s nonfiction, We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live, is plastered with the now cliché image of a young Joan leaning out the window of a convertible, looking ill-amused, cigarette dangling loosely from her right hand. This image fails to encompass Didion’s language, narrows her persona, and freezes her in youth. It does not do justice to the full scope of her prose—the breadth and depth of each essay, the deftness of her syntax.

So I wonder whether, for the sake of a genre that is, by definition, grounded in the real, nonfiction books might do better without cover art. If book covers were blank, would people still read? Without titles and cover art? With only words? And yet our visually oversaturated society calls, always, for images. Sometimes, it seems, for pictures before language in a world where the written word is increasingly phasing out of fashion. We cannot realistically afford to eliminate the visual. The connection between images and text and the space between them is flush with meaning. Yet as readers of nonfiction, it seems we are obligated to attempt to access the author’s story in its purest from. We owe it to them not to fictionalize fact. At root, then, does paratext cheapen nonfiction text?