Abstract: The 1960s and 70s were a tumultuous time for Hamilton. The Hill witnessed many changes, from the Civil Rights Movement to the Vietnam War to the Hamilton-Kirkland merger. The bubble that protected the College from the nation’s larger political events was, proverbially, popped. Students started protests, sit-ins and petitions on campus, and some even went off the Hill to march with others in Washington. However, by the 80s, the “Hamilton cool,” a epithet from the 60s for the quintessential, disengaged Hamilton student who didn’t care about classes, politics or anything else, had settled back into place with frequent vandalism, fraternity domination of campus culture, and virulent racism. Simultaneously, the growing issue of apartheid in South Africa mobilized students to fight for Hamilton to divest from its corporate holdings in South Africa and to think about issues of diversity and racism on campus. Tensions between administration and students reached an all time high and ended with twelve students who were suspended and who subsequently sued the College. By 1989, things seemed to have largely quieted down, and it wasn’t until September 11, 2001 that the Hill saw again a concerted, campus-wide effort to engage politically with the nation again and hold peace protests.

In addition to looking at how the Hamilton community responded to some of these events, we will address some of the ways in which Asians and Asian Americans have, and have not, been involved on campus. While Asian cultural clubs have existed at Hamilton since 1987 (ACS, ASA and then, finally, ASU), they have never been part of the Days-Massolo Center. One reason the DMC gave was that ASU had traditionally been centered around Asian culture and festivities rather than more “serious” and educational initiatives that strive to amplify marginalized voices. With the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes during the COVID-19 epidemic, ASU became more politically engaged and partnered with the DMC for events such as Cafecito Friday.

Click on any of the links below if there is a section you would like to go directly to.

- Shifting Tides: A Change in Tone to the Vietnam War

- The Kirkland Factor

- Welcome to the Animal House: Hamilton in the Eighties

- “Before We Assume”: The Effect of 9/11 on Hamilton’s Campus

- Asian Americans in the Present Day: A Personal Take

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

Shifting Tides: A Change in Tone to the Vietnam War

By Rachel Lu and Maya Nguyen-Haberneski

“I don’t remember Asian American students on campus, but there may have been some anti-Asian racist pronouncement having to do with the Vietnam War. Partly it was half-joking, the way Trump would half-joke, where it was really serious but it also was said in a half-joking manner and it wasn’t directed against anyone personally. It was about the Vietnamese, I guess you would say.”

– Randolph Splitter, Class of 19681

The jump from 1846 to 1960, over a hundred years, is significant but necessary. After Zeng Laishun’s matriculation and subsequent departure, the next major event that affected campus and the history of Asian/Asian Americans at Hamilton was the Vietnam War, which, because of racial challenges, forced Asian Americans to confront their racial identity.2 The campus was affected because of the question of the draft, which many Hamilton students fought against late in the war either on the basis of moral grounds or on what they felt to be a clear lack of objectives.3

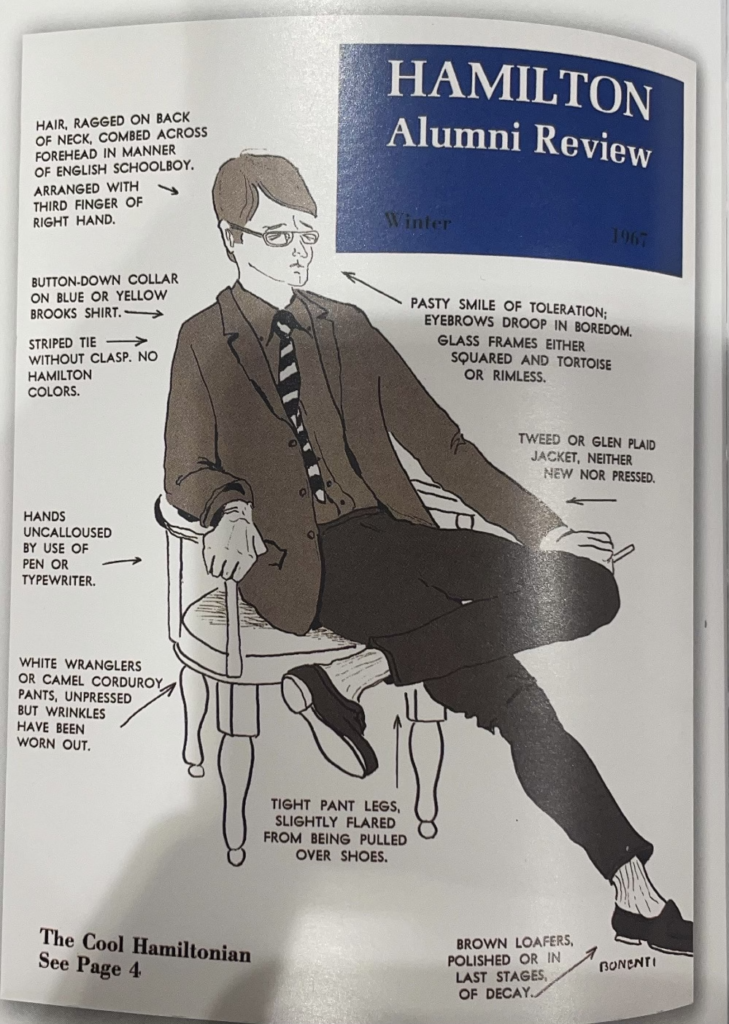

In many ways, the sixties and seventies, which included the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and the Hamilton-Kirkland merger, was a turning point for Hamilton.4 The Vietnam War in particular spurred students to fight for a larger political cause and consider concerns outside the bubble of the Hill for seemingly the first time. However, it wasn’t until later in the war that the student body seemed to be working in concert together to oppose the war. For the first twelve years, at least, much of the campus remained removed from the larger events in the nation surrounding them. This apathetic, conservative attitude was known as the “Hamilton cool,” an epithet that referred to the conformist demeanor of the academically and politically disengaged Hamilton student.5 Ken Casanova, Class of 1968, reflected that “the apathy, to some extent, was a product of the conservatism, conformity, and ‘preppie’ style of thought and behavior.”6

In an interview with Publius Virgilius Rogers Professor of American History and author of On the Hill 1812-2012: A Bicentennial History of Hamilton College Maurice Isserman, he notes how Hamilton was “a very white … very local college … to be anything as exotic as an Italian from Utica put you outside the mainstream. So the mainstream was not just white but white Protestant. For example, the fraternities by national charters were restricted to white Christians. In fact, they didn’t even admit Catholics until about 1940.”7

Conservative would also be a way of describing the majority of Hamilton students up through the early sixties. There was a straw poll in 1960 regarding student and faculty preferences for presidential candidates. The Republican candidate, Richard Nixon, was favored by 54 percent of the students while John F. Kennedy, the Democratic candidate, received support from 35 percent of the student body. This was the last time, using recorded data through 2011, that Hamilton students and faculty would favor the Republican candidate in presidential election polling.8 These results are significant in that they suggest the beginning of a gradual shift toward more liberal views on campus. There were also many other factors, some of which are expanded upon below, that contributed to more liberal attitudes on campus. However, it should be noted that although there was a shift toward favoring Democratic presidential candidates during the early/mid sixties, at that time the majority of Hamilton students supported US involvement in Vietnam. In other words, party affiliation was not a great indication of one’s opinions about the War. This is also evident when looking at the decisions made by Democratic presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. JFK, elected in 1960 steadily increased the number of troops he authorized in South Vietnam.9 His successor, LBJ, was in office during the US military operation called Operation Rolling Thunder, a bombing campaign that resulted in 43,000 civilians killed and wounded.10 So even though Hamilton students and faculty began favoring Democratic presidential candidates in the mid-sixties, it is important to keep in mind the amount of destruction in Vietnam that occurred while those leaders were in power.

According to Isserman, the April 23, 1965 issue of The Hamilton College Spectator11 was the first to mention the war in Vietnam in an on-campus publication.12 Half-way down the front page the headline reads “Students March in Protest of Vietnam,” the march in question being the March on Washington to End the War in Vietnam.13 In order to challenge the United States’ actions in Vietnam, an estimated 20,000 students came together from across the nation. This prompted the police on scene to describe the protest, as quoted by the Spectator, as “the largest demonstration ever held near the White House grounds. Robert Moses, a Civil Rights leader that graduated from Hamilton in 1956, gave the opening address in which he accused the US of being a nation that “produce[s] racists who wantonly bomb and murder in defense of their own traditions.”14 Representatives from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and the Women’s Strike for Peace were also in attendance. Despite the significant turnout, only four Hamilton men took part in this event, making Hamilton’s delegation one of the smallest from the Northeast. Other New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC) schools, such as Williams and Amherst, sent forty to sixty demonstrators. Larger schools, such as the University of Buffalo and Cornell, sent closer to three busloads of students and faculty.15 When asked to speculate on why Hamilton sent so few students in comparison to similar-sized NESCAC schools, Randolph Splitter, Class of 1968 pointed to College’s geographic isolation.16 As a college in upstate New York, Hamilton doesn’t have easy access to large cities like New York City or Boston. Splitter also suggested that the conservative leanings of Hamilton’s student body factored into the low representation at the protest. For instance, while the Spectator recognized the good intentions of the protestors, the publication “warned editorially that ‘communist Chinese expansion’ in Southeast Asia justified the American war effort.”17 The following issue (April 30, 1965) of the Spectator included two separate letters to the editor which stated that the majority of Hamilton students disagreed with the goals and organizers of the march.18

Fast forward to the November 12, 1965 issue of The Hamilton Spectator to find a letter to the editor written by Splitter.19 He urged members of the Hamilton community to sign a petition that was left in the library. The petition was intended to be sent to President Lyndon B. Johnson to express opposition to the war in Vietnam. Some people signed the petition, while others scribbled over it and added nonsense names such as “Charlie Pinko.” Unfortunately, a week after his initial announcement, Splitter wrote another letter to the editor which stated that the petition was stolen. He expressed his frustration and sorrow about the missed opportunity to inform the President by saying the following: “If we could have mailed the petition, it would have had a chance; now it has none.”20

While both the March on Washington to End the War in Vietnam and the petition attempt were examples of Hamilton students taking action in opposition of the war, the men who participated in those events appear to have been in the minority. The Hamilton Spectator conducted a poll in December 1965 to get the campus opinions about the war. According to the poll, “nearly half of the faculty and a majority of the students favor stepping up the American war effort in Viet Nam.” Of the 30 percent of faculty that responded to the poll, none of them agreed to the withdrawal of American troops as a solution. In fact, 26 percent of the faculty “indicated that the US should use atomic weapons against North Viet Nam and Red China.” Although 62.7 percent of students and 43.2 percent of faculty members did not sympathize with the anti-war demonstrators, most of them felt like the demonstrators had a right to protest openly.21

The following February, Senator Robert Kennedy led a question and answer session. While other topics were discussed, talk about the Vietnam War dominated the conversation. Someone asked the Senator if the US was doing all it could to bring peace to the situation. Senator Kennedy replied by saying “we are making an effort,” At one point during the session, Kennedy had polled the audience, by show of hands, to get their opinions about the war. Here are the results as reported by The Spectator: “About five per cent were in favor of pulling out of Vietnam immediately. About 15 per cent indicated they favored resumption of the bombing, including bombing Hanoi. About 25 per cent were in favor of Johnson’s present policy. The remaining 55 per cent favored Johnson’s present policies, ‘but with strong reservations.’ Neither Kennedy nor the students said what these reservations entailed.”22 The results of this poll were not that dissimilar from the 1965 Spectator poll. Both polls show roughly the same percentage of participants who favored US withdrawal from Vietnam, and the polls showed similar statistics for those who supported US actions in Vietnam. Despite the results of these early polls in 1965 and 1966, The Spectator, a publication assumed to express the opinions of Hamilton’s student body, endorsed Kennedy’s bid for President on the front page of its April 5, 1968 issue. Kennedy ran to seek “new policies,” the first one listed being a policy change to “end the bloodshed in Vietnam and in our cities.”23 This suggests a shift in opinions regarding the war between Kennedy’s Q&A session in 1966 to his endorsement by The Spectator in 1968. A significant number of events, expanded upon below, helped Hamilton make this shift.

Previously, Hamilton had a Double F policy that stated students could not miss their last class right before vacation otherwise they would receive a Double F.24 The suspension of the double F policy right before Spring Break of 1966 allowed students to go March on Washington without receiving that penalty. Later on, the Double F policy was finally lifted.25

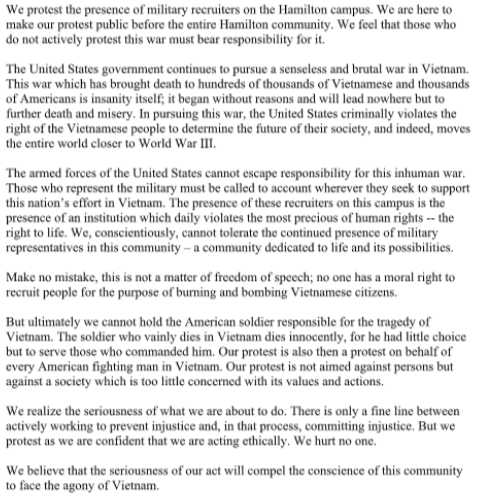

While there was a change in anti-war sentiment among Hamilton students, the campus was still divided on the war. The fall of 1967 saw this conflict come to a head in the form of a clash between members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) chapter and members of Alpha Delta Phi. The photo to the left captures this confrontation.26 Thirteen students from SDS formed a human chain across College Hill Road in an attempt to block a Marine recruiter vehicle from coming onto campus but were physically broken up by fraternity members. The vehicle drove past the protestors and fraternity members, and both student groups followed the recruiter to Bristol Center.27 Ken Casanova read a speech he had written in advance behind Bristol, where the protestors had formed another line in front of the door to block the entrance. In his speech, Casanova declared, “Make no mistake, this is not a matter of freedom of speech; no one has a moral right to recruit people for the purpose of burning and bombing Vietnamese citizens.”28 Associate Dean Depuy approached the protestors and asked them to move aside, and the students obliged willingly.

When a recruiter returned later in the year on December 12, 1967, students protested again. Instead of blocking the recruiter’s path, however, they stood in front of his table and passed out flyers about the war but did not stop other students from communicating with the recruiter. According to Casanova, there were around “50 students at this protest – clearly ‘moderate’ students who had joined in protest.”29

As the war progressed, students became more and more involved. In a way, the clash in the fall of 1967 set off the anti-war student activism that was to take place on the Hill the following year. Student “sprawl-ins,” students lying around a recruiter’s booth and preventing access to him, were soon declared an unacceptable “form of demonstration” by the Faculty Committee on Student Action. Faculty also got involved when the Hamilton Chapter of the American Association of University Professors “requested a ban of future on-campus military recruitment.”30 However, the Board of Trustees rejected the student and faculty call to ban military recruiters from campus and the secondary appeal by the Student Senate.31

“At this point it was clear there was a rift between the campus — faculty and students and the administration and trustees,” Casanova wrote in an email to Christopher Wilkinson, Class of 1968, later on.32

When the Marine recruiter returned to campus the second time in March 1968, students protested by way of entering President John Wesley Chandler’s office instead. Unexpectedly, Chandler “turned the confrontation into a two hour ‘seminar,’ during which he welcomed questions yet indicated no willingness to change his position.”33 The confrontation-turned-seminar ended with a caution that three warnings would be issued the next time anyone disturbed his office and that disciplinary measures would be imposed on students who disregarded the warnings. Despite this, Chandler had already contacted government officials regarding the draft reform and was willing to personally provide financial and legal assistance for “any student reclassified as a result of orderly protest.”34 Earlier that year, the Student Senate had passed a motion requesting that “the College cease to invite military recruiting officers until the Federal Government makes it clear that the draft not be used as a punitive device and that the rights of our students will be protected by due process of law.”35

The issue of military presence on campus had dominated the front pages of The Spectator during the 1967-68 academic year—which makes sense. The draft was a significant topic of discussion at the all-male institution and the attempts to block military recruiters on campus were physical, outward displays of the students’ opposition to the war. However, there were also smaller, less confrontational ways in which people showed their objection to the war that deserve recognition. The March 1, 1968 issue of The Spectator reported on a chapel service that was held to repent for the war in Vietnam. Despite the article’s location on page 4, the service attracted more than fifty people. It provided the Hamilton community with an important space where people had the opportunity to reflect upon the “sorrows of the war.” People asked for forgiveness for the actions of their country such as the use of “napalm and precision bombing,” as well as forgiveness for the consequences like the “rivers polluted with blood” and “the counting of dead like the hits and runs of a ball game.”36

“[B]y 1967-68 Hamilton had come a ways toward political activity and awareness regarding the war – but it was among a minority,” Casanova said. “[E]ven this level of activity did not break the Hamilton mold of inactivity and apathy.”37

Finally, the recruiting issue came to a standstill when military recruiters were banned for the 1968 year after a Naval Aviation officer refused to sign the affidavit that requested recruiters agree to not report the names of student protestors.38 However, this decision was reversed the following academic year when Chandler allowed a recruiter to come onto campus. As referenced a few paragraphs above, Chandler’s decision was influenced by the Board of Trustees’ commitment to provide support, both financial and legal, to “students reclassified as a result of an orderly demonstration.”39

The campus conflict over the Vietnam War was briefly resolved through the Moratorium in 1969, a national organized protest, which united faculty, students, staff, and even local Clinton residents. During this time, Hamilton students canvassed Utica with a petition that requested a withdrawal of all troops and gained over 4,500 signatures. However, this short-lived unity was soon broken over visiting military recruiters, the perpetual thorn in Hamilton’s side. This time, Kirkland students joined Hamilton students in blocking the Marine recruiter, but unlike two years before, these students were placed on disciplinary probation for three months.40

In October 1969, Chandler signed a public statement that “urged President Richard Nixon to step up the pace of troop withdrawals from Vietnam.”41 Seventy-eight other college presidents joined Chandler in signing this statement. Perhaps the recent anti-war protests and the heated discussion pertaining to the presence of military recruiters on the Hill influenced Chandler’s decision to sign the statement.

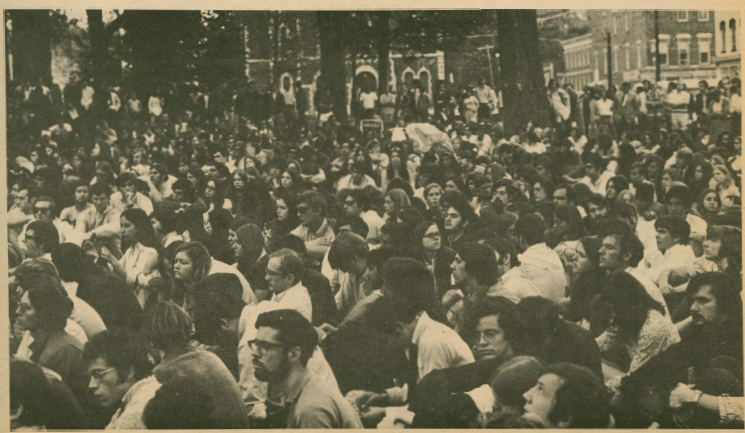

On April 30, 1970, after President Richard Nixon announced the American invasion of Cambodia, some college campuses began protesting within the hour. The Kent State shootings, which resulted in the National Guard killing four students and injuring nine others, increased the fervor of collegiate protests around the nation. On the Hill, Kirkland courses were stopped with faculty writing final evaluations based on completed work while Hamilton courses continued with faculty allowing striking students to request credit for their work to date. According to The Spectator, “[s]tudents created a committee to run a United States Saving Bond redemption drive and to investigate the use of stock proxies in corporations holding government defense contracts.”42 Teach-ins were also organized, and the Class of 1970 decided to graduate sans cap and gown and donate that expense to the Student Strike Fund. Even the Interfraternity Council (IFC) pitched in by cancelling all social functions and donating that money.43 After a tumultuous several years, Hamilton was not only united again but united on a progressive issue that expanded the traditional confines of student political involvement. Instead of fighting with each other, fraternity members, who perhaps upheld more traditional, conservative views, and more liberal students were fighting for the same cause. Together, around seven hundred Hamilton and Kirkland students, as well as the presidents of both institutions, marched down to the Village Green where Clinton residents awaited in apprehension for smashed windows and general chaos.44 Having seen news footage of Kent State and other student demonstrations, local residents and merchants boarded up windows but were surprised by the peaceful protest and the subsequent clean-up.

In two years, Hamilton had changed considerably, with the population of students taking an interest outside of the bubble and protesting the Vietnam War shifting from the minority to a majority. Casanova remarked, “I left in June, ’68, and I would never have believed that Hamilton would have moved so far so quickly. Such a thing to me [the 1970 Village Green strike] at Hamilton when I was there would have been unthinkable. It would have represented a transformation of the campus – of college life and thought. So I would have to ask what the ingredients were that led to such a (for Hamilton) radical change. I expect a sign, a seed of this, was the new crop of students in the freshman class of ’68 which I mentioned above. Kirkland I’m sure had an impact, as well as activity across the country. Still I even now find it hard to believe.”45

The addition of Kirkland women on the Hill undoubtedly influenced Hamilton’s political atmosphere. Isserman observes in On the Hill that the “arrival of Kirkland women, who tended to come from more liberal backgrounds than their Hamilton counterparts, reinforced anti-war sentiments.”46 To read more on this topic click here.

While perusing through The Spectator, Alumni registers, The Hamiltonian, we kept returning to one question: where were all the Asians? We wanted to know whether they were involved in the protests, how the Vietnam War might have impacted them, and if possible, speak with them to hear about their experiences. Unfortunately, we struggled to locate any Asian/Asian Americans during this era. Splitter noted that from his memory, he did not “remember a single Asian or Asian American student on campus.”47 Wilkinson observed that there were “no Asian or Asian Americans in [his] class” and only one Black student who dropped out “due to a chronic health condition” but that there were two students from China, Wu Ching-Mae and Yu Hung Chang, his sophomore year that attended Hamilton.48 We could not find them.

Despite our struggle to locate Asian/Asian American people, it is apparent that there was at least some interest in Asian/Asian American welfare and culture as an Asian Studies minor was created in the 1967-68 academic year, the formation of which President Chandler had encouraged. In an email to me, Wilkinson links a growing concern for the Vietnam War with the development of the Asian Studies minor. When I asked whether anyone had verbally mentioned the two in conjunction with each other, Wilkinson wrote, “To my knowledge, there was never an explicit comment regarding a connection between the war and the Asian studies curriculum. There did not need to be: the War was on everyone’s mind, and this cohort of faculty had already been involved in at least two teach-ins about the history of Viet Nam leading up to the War as well as sat for interviews for reporters from The Spectator.”49

In addition, Professor of History Edwin B. Lee, known as “Asian Ed” on campus, helped create a strong East Asian curriculum component in the History Department. Though his specialization was in Japanese History, he taught many other Asian history courses, such as a general Asian history course, the history of modern China, and the history of modern Japan, since the 1950s.50

Isserman remarked, “There is a kind of a throughline there for a half-century or so in terms of Hamilton’s academic offerings. In terms of Asian Americans enrolled in Hamilton, it’s a kind of thin line, but in terms of a broader engagement with Asia, it’s surprisingly strong.”51

It is certainly challenging to write a history on a group of people who have seemingly not existed on campus, or if they did, have left little to no trace in the annals of Hamilton history. The combination of the invisibility and nonexistence of Asian/Asian Americans is not surprising, both because Asians have been a minority population throughout US history with just a 5.7 percent national population today and because Asians and Asian issues have historically been silenced whether that has been imposed by others or self-imposed. Isserman mused, “You know, I was looking back at the book [On The Hill], and I was thinking, ‘Not a lot in here about Asian students.’ You have to go back to 1846. So that’s definitely a shortcoming in the book, but in some ways, it reflects the kind of limited presence of Asian students for most of the time I was here. The groups that were much more visible were Black and Latino.”52 The history of Asian/Asian Americans at Hamilton, then, is inevitably connected to Black and Latinx students who had to endure racism—verbal harassment, physical threats, microaggressions—and create a platform to fight against it. The discussion of diversity and race at Hamilton, prompted by Black and Latinx issues, throughout the late 20th and 21st century allows our research group to undertake our racial project today.

Notes

1. Randolph Splitter (Co-Founder of Students for a Democratic Society at Hamilton College), interviewed by Rachel Lu, August 3, 2021

2. Asian Americans, episode 4, “Generation Rising,” Executive producer Jeff Bieber, written by Grace Lee and Aldo Velasco, aired in May 2020, on PBS, https://www.pbs.org/weta/asian-americans/episode-guide/episode-4-generation-rising/

3. We recognize that World War II also affected Asian American populations as not only those of Japanese descent were sent to internment camps but others of Asian heritage who were mistaken as Japanese people as well. In addition, we are aware of the racism that Asian/Asian Americans endured during this time. However, World War II and its race-related issues largely did not affect Hamilton. While students were certainly sent off to the war, questions of race, justice, equality, etc, that we see raised during the Hamilton Vietnam War period were not a focal point during World War II.

4. In comparison to the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement did not mobilize as many Hamilton students. Thomas A. Kuck, “The Roots of Protest,” (The Spectator Winter Magazine, January 1987, 26-31) wrote that “the Civil Rights Movement at Hamilton never left the back burner of campus controversy. It had to compete against ecology, women’s liberation, and Vietnam for the public’s attention and generally lost” (Kuck 1987, 28).

5. Maurice Isserman, On the Hill: A Bicentennial History of Hamilton College, (Clinton: Trustees of Hamilton College, 2011), 260.

6. Ken Casanova, Questionnaire response to Clark Pettig, February 4, 2003.

7. Maurice Isserman, interview by Rachel Lu, August 4, 2021, Clinton, NY.

8. Isserman, On the Hill, 262.

9. “1961-1968: The Presidencies of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson,” Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, accessed August 14, 2021, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/foreword.

10. Central Intelligence Agency Directorate of Intelligence, No, 1378, PDF file, https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/041/04111146007.pdf.

11. It should also be noted that the full name of the student newspaper is The Hamilton College Spectator. However, future references to this publication within the text, not the notes, will refer to it as simply the Spectator.

12. Isserman, On the Hill, 296.

13. “Students March in Protest of Vietnam,” Hamilton College Spectator, April 23, 1965, 1.

14. Robert Moses as quoted by the Spectator. It should be noted that the previous quotation was not an official quote from police description, but rather a quote taken from the April 23, 1965 Spectator article.

15. “Students March,” 1.

16. Splitter, interview.

17. Isserman, On the Hill, 296.

18. “Letters to the Editor,” Hamilton College Spectator, April 30, 1965, 2. There were two letters referenced, one written by Lawson Scholnicoff, and the other signed by Tom Pasko.

19. Randolph Splitter, “Viet Nam,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 12, 1965, 4.

20. Randolph Splitter, “Viet Nam Petition,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 19, 1965, 4.

21. Thomas Crane, “HamiltonStudents [sic] Yet Unaffected By Viet Nam Draft: Students Receive 2-S Deferments,” Hamilton College Spectator, December 3, 1965, 1-2.

22. “Kennedy Draws Large Crowd In Question-Answer Session,” Hamilton College Spectator, February 11, 1966, 1.

23. “A Spectator Editorial – Kennedy for President,” Hamilton College Spectator, April 5, 1968, 1.

24. Splitter, interview.

25. Maurice Isserman, email sent to Rachel Lu, August 13, 2021.

26. “Violence Disrupts Students Protesting Against Marine Recruiting in Center,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 3, 1967, 1.

27. Kuck, “Roots of Protests,” 26-31.

28. Ken Casanova, email sent to Rachel Lu, August 10, 2021.

29. Ken Casanova, email sent to Chris Wilkinson, March 31, 2018.

30. Kuck, “Roots of Protests,” 26-31

31. Vin Strully, “Chandler Notes Trustee Action,” Hamilton College Spectator, February 2, 1968, 1.

32. Ken Casanova, email sent to Chris Wilkinson, March 31, 2018.

33. David Rogers, “Chandler Sit-in: Where to Now?,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 1, 1968, 1.

34. Kuck, “Roots of Protests,” 26-31.

35. Ken Casanova, email sent to Chris Wilkinson, March 31, 2018.

36. “Over Fifty Attend Chapel Service of Repentance for War in Vietnam,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 1, 1968, 4.

37. Ken Casanova, Questionnaire response to Clark Pettig, February 4, 2003.

38. “Navy, Army, Air Force Barred for Refusal to Sign Statement,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 8. 1968, 1.

39. Bruce Nichols, “Hamilton Admits Recruiter President Explains Reason,” Hamilton College Spectator, October 11, 1968, 1.

40. “Recruiter Issue Erupts Anew,” Hamilton College Spectator, October 31, 1969, 1.

41. Isserman, On the Hill, 285.

42. Spectator note.

43. Shortened note

44. Isserman, interview.

45. Ken Casanova, Questionnaire response to Clark Pettig, February 4, 2003.

46. Isserman, On the Hill, 298.

47. Splitter, interview.

48. Christopher Wilkinson, email to Rachel Lu, August 3, 2021.

49. Wilkinson email.

50. Hamilton College, 1959 Course Catalog, Clinton, NY.

51. Isserman, interview.

52. Isserman interview.

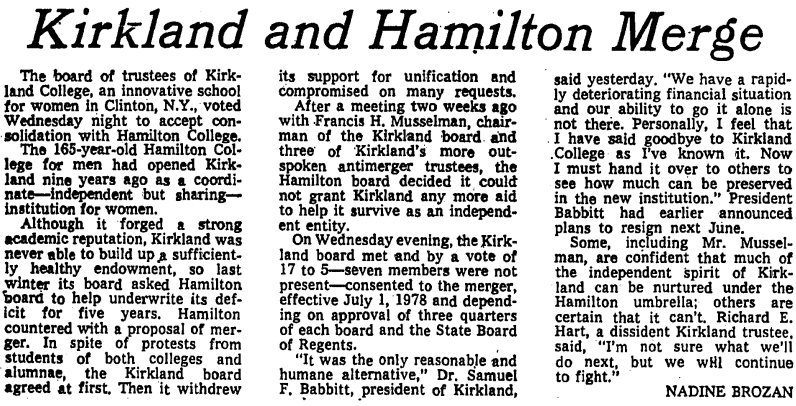

The Kirkland Factor

By Maya Nguyen-Haberneski

“We were very, very different campuses because the Hamilton men were typically very conservative politically and came from Hamilton families who lived in this country for generations. And [they] were not at all ready for the artsy hippies who moved in across the street.”

– Denise Moy, Kirkland alumna Class of 1975 1

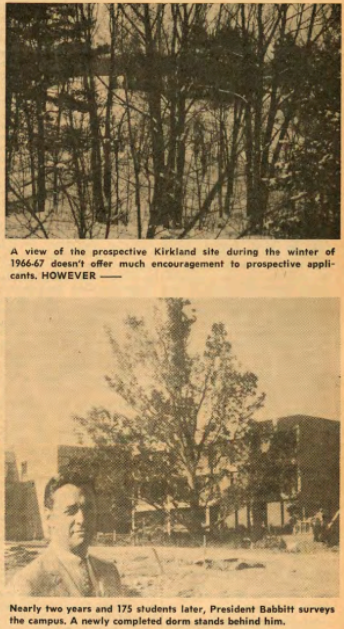

Current students and recent alumni of Hamilton College may refer to the land and buildings located south of College Hill Rd. as the “dark side,” but in 1968 that space welcomed Kirkland College’s charter class. Despite being established and existing during a time in which the popularity of single-sex institutions was declining,2 Kirkland was committed to providing its all-female student body with an education designed to, according to Kirkland’s 1966-69 Catalog, prepare its students to be “intellectually alert”.3 In doing so, Kirkland built an experimental and progressive atmosphere on the Hill that counterbalanced Hamilton’s more traditional environment. For instance, instead of getting grades at the end of the semester like their male counterparts, Kirkland students received written evaluations. And rather than having desks organized in rows, a layout best suited for lecture-style classes where student-to-student interactions were discouraged, many Kirkland faculty configured the desks into a circle for seminars.4 Vintage72, Kirkland’s yearbook for its charter class, even had a series of blank pages in which a student had “the opportunity to record her own class history”.5 After gaining a better sense of Kirkland’s more progressive and liberal environment, my research led me in three directions: How did this all-women’s school affect sentiments about the Vietnam War at Hamilton? To what extent did racial diversity fit into Kirkland’s agenda? And finally, what legacy did Kirkland have on Hamilton’s curriculum?

Prior to the establishment of Kirkland, Hamilton as an institution appeared to be averse to change and progressive ideas. Nancy Rabinowitz, a professor who taught at Kirkland and transferred to Hamilton after the two colleges merged, described Hamilton as having “a long and distinguished racist and anti-semitic history.”6 She went on to describe her impression of Hamilton’s general environment up through the mid-sixties: “It was conservative. It was white. It was male. It was Christian. And it was quite happy being those things.”7 Kirkland was different.8 Denise Moy, a Kirkland alumna who concentrated in Asian Studies, described her fellow classmates as being “much more liberal and anti-war than the men.”9

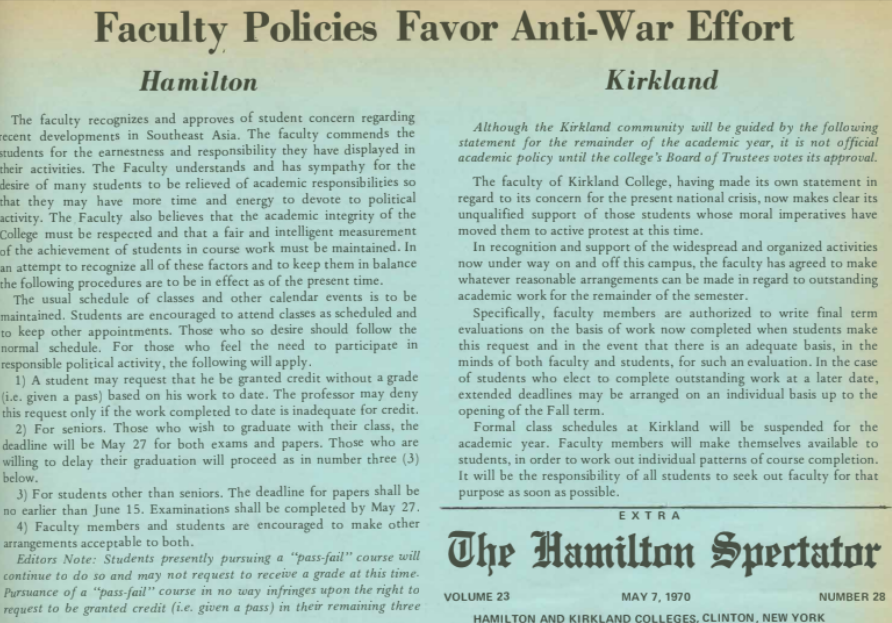

To understand the difference between the two institutions, which had their separate administrations and Board of Trustees, it helps to look at how each of them responded to a protest in May of 1970. The aim of the protest, as agreed upon by both Hamilton and Kirkland students, was to leave classes as a response to the invasion of Cambodia and the killings at Kent State.10 While Hamilton faculty acknowledged and applauded its students’ actions, “the usual schedule of classes and other calendar events” were maintained.11 On the other hand, Kirkland faculty “voted to suspend all formal classes for the remainder of the year.”12 to demonstrate their “unqualified support of those students whose moral imperatives have moved them to active protest at this time.”13 Hamilton’s response was more traditional, while Kirkland leaned into the liberal attitudes of its student body. In fact, these liberal attitudes of the Kirkland women helped reinforce anti-war sentiments on the Hill.14 In addition to the Cambodia/Kent State protest, Hamilton and Kirkland students came together to pray for peace in Vietnam during a moratorium service15 and to attempt to block a marine recruiter from the Bristol Center.16

In addition to researching how the all women’s school affected the anti-war movement on the Hill, I was interested in looking at the degree to which Kirkland’s progressive attitudes transferred to racial diversity on campus. As an Asian woman myself, I was hoping to identify and interview Asian women who attended Kirkland and learn more about their experiences of being both a woman and Asian at that time. After sifting through yearbooks I was able to find a couple of women who I believed to be of Asian descent, but overall I was disappointed with the lack of racial diversity. Despite a statement on page 68 of Kirkland’s 1966-69 Catalog proclaiming that the College actively sought “a national student body representing all races, creeds, and backgrounds,”17 Kirkland’s student body remained overwhelmingly white, suburban, and middle class. In fact, the charter class only enrolled three African American women.18 Moy, who was on Kirkland’s admission committee her senior year, said that she didn’t remember “the school actively seeking out more students of color. That wasn’t really a thing.”19 There seemed to be a disconnect between Kirkland’s attitudes which have, time and time again, been described as “progressive,” and their practices regarding racial diversity on campus. Though Kirkland women fought for women’s equality, their focus seemed to be largely on white, middle to upper class women. However, these attitudes and practices appeared to become more in sync after discovering a 1972 New York Times article that indicated the wishes of President Samuel Babbitt, along with many Kirkland faculty and students, to increase representation of Black and Puerto Rican students on campus.20 When asked about Kirkland’s intentions to increase racial diversity on campus, Rabinowitz suggested that there was an effort to admit more students of color. Both Rabinowitz and Moy mentioned the activism of the Black and Puerto Rican Student Alliance, but recognized that there was no comparable organization for Asian/American students.21 Rabinowitz even acknowledged having few Asian students in her classes.22 In 1978 Kirkland merged with Hamilton after being unable to provide the funds to stay open as a separate institution.23 It’s impossible to know whether Kirkland would have admitted more Asian women and other people of color had it remained an autonomous all-women’s college. However, one could only hope that would be the case given Kirkland’s statements regarding admissions which appeared to become increasingly inclusive in nature.

Despite Kirkland’s lack of racial diversity within its student body, the College provided classes that allowed students to learn about select Asian languages and cultures. Although it was subject to faculty appointment, Kirkland’s 1966-69 Catalog offered an introduction to Chinese language and tradition.24 Additionally, Kirkland’s introductory anthropology class focused on “selected peoples of Africa, India, and China.”25 Professor Rabinowitz mentioned that she addressed topics of race through texts such as Balzac’s Girl with the Gold Eyes and Brecht’s Good Person of Szechwan.26 A political science class that concentrated on Asia was one of Moy’s favorite classes that she took as part of her major. Hamilton had previously offered a few courses in Asian history,27 but classes on Asian language, culture, literature, or political science didn’t seem to be offered until Kirkland opened its doors. Yet, despite the protests in opposition of the Vietnam War on the Hill and across the nation, Moy said that there were no classes that “covered anything about Vietnam culture or politics in the seventies. It makes you think about, you know, why were we involved in the war and nobody knew about the country?”28 As mentioned above, Kirkland merged with Hamilton in 1978, and thus made significant contributions to departments such as Art History, Comparative Literature, Sociology, and Theatre and Dance.29 Although many students and alumni, from both Kirkland and Hamilton, were not happy with the merger/take over, I was delighted to see the lasting impact Kirkland had on Hamilton’s campus. When looking at specific classes in Hamilton’s 1996-97 course catalog that were offered under the aforementioned disciplines, I observed that many of them were devoted to Asian art and culture. Courses ranged from looking at the Heroes and Bandits in Chinese History and Fiction to Asian Theatre.30

Notes

1. Denise Moy, interviewed by Maya Nguyen-Haberneski, August 9, 2021.

2. Kirkland College was popular among students who were also considering Sarah Lawrence College and Bennington College, both of which were all women’s colleges. They both turned to coeducation before Kirkland opened its doors. According to Isserman (On the Hill: A Bicentennial History of Hamilton College, 2011, 283) , other small liberal arts colleges in the northeast, such as Williams, Bowdoin, and Amherst, went coed in 1970, 1971, and 1975 respectively.

3. Kirkland College, Catalog 1966-69, Clinton, NY, 8.

4. Nancy Rabinowitz, interviewed by Maya Nguyen-Haberneski, August 3, 2021.

5. Kirkland College, Vintage72, Clinton, NY, 1972, 71.

6. Rabinowitz, interview.

7. Rabinowitz, interview.

8. In the interview, Professor Rabinowitz suggested that the differences between the two colleges were partially a result of them being established in different centuries. Hamilton, which was established in 1812, was created in a time when there was overt racism and anti-semitism. Kirkland, however, was chartered in 1965. In that respect, “Kirkland was new and came of age in a time when those ideas [racism and anti-semitism] were not acceptable” (Rabinowitz, interview).

9. Moy, interview. Moy did, however, mention that the Kirkland women weren’t up for the draft like their male counterparts, and she acknowledged that “that changed the dynamic quite a bit.”

10. Steve Kinney and Hal Higby, “Hill Students Leave Classes to Plan Against War: Faculty Respond to Boycott,” Hamilton College Spectator, May 5, 1970.

11. “Faculty Policies Favor Anti-War Effort: Hamilton,” Hamilton College Spectator, May 7, 1970, 1.

12. Barbara Sanders, “Kirkland Faculty Halts Classes,” Hamilton College Spectator, May 7, 1970, 1.

13. “Faculty Policies Favor Anti-War Effort: Kirkland,” Hamilton College Spectator, May 7, 1970, 1.

14. Maurice Isserman, On the Hill: A Bicentennial History of Hamilton College, (Clinton: Trustees of Hamilton College, 2011), 298. It should be noted that while Kirkland women helped reinforce anti-war sentiments on the Hill, there were a small minority of Hamilton men that were quite vocal in their opposition to the Vietnam War before Kirkland women arrived on the Hill. More information about Hamilton’s response to the Vietnam War can be found in the section above.

15. Barbara Sanders, “ Moratorium Chapel Held To Pray for Vietnam Dead,” Hamilton College Spectator, October 17, 1969, 1.

16. “Recruiter Issue Erupts Anew,” The Hamilton College Spectator, October 31, 1969, 1.

17. Kirkland College, Catalog, 68,

18. Isserman, On the Hill, 288.

19. Moy, interview.

20. M.A. Farber, “Kirkland College’s First Class of 116 Women Wins Degrees,” New York Times, May 26, 1972, https://www-proquest-com.ez.hamilton.edu/historical-newspapers/kirkland-colleges-first-class-116-women-wins/docview/119590440/se-2?accountid=11264

21. Moy said there were about 20 students at Kirkland when she was there who were of Asian descent. They attempted to create an Asian Student Union on campus, but “there were hardly any of us […] We were such a disparate group of people in terms of our academic interests and where we were from. I would say the only things we had in common were black hair and brown eyes. So we got together, just figuring well we really should get together, but couldn’t come up with any reason to socialize beyond the fact that we were Asian and Asian American. So it just sort of fell apart.”

22. Rabinowitz, interview.

23. Nadine Brozan, “Kirkland and Hamilton Merge,” New York Times, July 29, 1977, https://www-proquest-com.ez.hamilton.edu/historical-newspapers/kirkland-hamilton-merge/docview/123276853/se-2?accountid=11264.

24. Kirkland College, Catalog, 40.

25. Kirkland College, Catalog, 42.

26. Rabinowitz, interview.

27. Most of these classes were taught by Professor Lee. In addition to an Asian history course, Hamilton’s 1959 course catalog listed classes on the history of modern Japan and the history of modern China.

28. Moy, interview.

29. Hamilton College, Hamilton College Catalogue: 1996-97, PDF file, https://hamilton.smartcatalogiq.com/

30. Hamilton College, Catalogue.

Welcome to the Animal House: Hamilton in the Eighties

By Rachel Lu

“In the 80s—I wasn’t here in the 80s—everything, I hear, was a dreadful decade. Students were not only uninvolved but sort of returning to the worst animal house inspired vision of social life and the domination of fraternities”

– Professor Maurice Isserman1

If the sixties and seventies were a progressive, forward-thinking era for Hamilton, then the eighties were a significant step back. As Isserman noted, “If you leap forward again to the mid eighties, it’s all animal house all the time on campus. You’d say, ‘Well, nothing really changed,’ but two steps forward, one step back.”2 Saying that Hamilton took a step back might be oversimplifying the mess that was the eighties. True, it was a decade full of overt racism, vandalism by fraternities, and a return to the Hamilton “cool,” an epithet for the quintessential, disengaged Hamilton student who didn’t care about classes, politics, or anything else.3 However, it was also a period in students organized an anti-apartheid campaign and, for the first time, fostered passionate, engaged discourse on diversity, race, and the curriculum.

One former professor spoke of her “disenchantment with the lack of intellectual community at Hamilton,” which informed her decision to leave. 4 The Spectator writer who interviewed her conceded, “The term ‘anti-intellectualism’ has received more than its share of wear and tear in my four years at Hamilton.” 5

By 1985, the question regarding the possibility of adding an Africana studies had already become a familiar debate on campus. As summarized by a Spectator writer, “The first reaction that a reader of this article might have is ‘Gee, hasn’t there been enough said about the lack of an Afro-American studies program at Hamilton College?” He goes on to quote Frederick Douglass, “If there is no struggle there can be no progress […] Power concedes nothing without a demand, men may not get all they pay for but they must pay for all they get.”6 On March 15, 1985, The Spectator dedicated a spread to interviews with President Carovano, a professor, and a trustee, asking each about the liberal arts before inquiring about an Africana studies program.7

At first dodging the question by talking about “redirecting efforts” among faculty, Carovano’s response, “So we have to be continually alert to insure that the institution is offering a program which is appropriate to its environment,” pits an academic institution as responding to the environment.8 That is, the institution is adapting to yield to changes that the environment demands, placing Hamilton in a posterior position. This calls to mind the student’s quotation of Frederick Douglass above: Power concedes nothing without a demand. In this case, because there has been no marked “appetite” for Africana studies, Caravano saw no need to create that program. Diversity in education then is not meant to push students to think critically and expand beyond white hegemonic tradition but instead, like the market, supplies only what is demanded. The trustee’s answer was also telling of this mindset. Chairman of the Board of Trustees, William M. Bristol commented, “If it fits in normally with the general academic load that we want students to have — fine. I have no negative feelings about it, though I don’t judge it to be necessary.”9 Only Professor of Chemistry Robin Kinnel’s response reflected student demands for an Africana studies program. He said, “[W]e probably pay too much attention to ourselves and not enough attention to, say South American, Japan, And [sic] China, which are incredibly important culturally and economically. There are too few people at Hamilton who understand and appreciate it. And I think our education process needs to evolve — not change, but evolve — to reflect that.”10

In March 1985, the Association of American Colleges (AAC) released “Project on Redefining the Meaning and Purpose of Baccalaureate Degrees.” Their findings from this four-year research project concluded that there was a general “decline and devaluation in undergraduate degrees.”11 The AAC suggested nine experiences essential to the undergraduate education, one of which included international and multicultural experiences. Reporting on this issue, The Spectator wrote that Dean Melvin B. Endy, Jr. was focused on the “[i]mprovement of the study of minority cultures in our nation, as well as increased emphasis on Asian, African, and Latin American studies is viatl [sic] as ‘we have not, in a systematic or comprehensive way, offered studies that break from mainstream, Western culture.”12

The issue of a lack of an Africana studies program, lack of minorities, and Hamilton’s refusal to divest from companies in South Africa all seemed rooted, as Greg Thomas points out in The Spectator article below, in Hamilton’s traditional values. As Lea M. Haber, Class of 1987, recalled, President Carovano had informed Lea that her problem was “that equity [was her] primary value while to others, the value of freedom of association and tradition triumph.”13 Tradition referring, presumingly, to the good old white boys’ club and “freedom of association” to Hamilton’s long history of fraternities that until 1940 did not even admit Catholics into its society.14

Greg Thomas, Class of 1985, compares Hamilton’s minority population and classes in comparison to other liberal arts schools in The Spectator.

Reacting to student requests, the English department hired a literature professor specializing in Africana studies for the following academic year. Finally, in response to student demands, an Africana studies department was created in the mid 1980s.15

Administration also verbally announced their desire to recruit more diverse Hamilton students, with Dean Endy specifying “more Hispanics and Asians.”16 The class of 1989 only had seven Hispanic students and seven Asian American students. Dean Thompson refuted the idea that the admissions process was unfair in some way in its treatment toward minorities, saying, “Admissions does give minorities a big advantage in getting accepted to Hamilton. 66% of the blacks who applied were accepted. 66% of hispanics and 66% of asians who applied were accepted. The rest of the freshman class had a 45% acceptance rate. If that’s not diversity […] I don’t know what is.”17

Simultaneously, students were calling for Hamilton to divest from its corporate holdings in South Africa, which was in the midst of a national crisis over apartheid. On March 10, 1986, the Board of Trustees announced to a crowd of around one hundred fifty students that they would not divest, citing that the companies the College held stock in adhered to the Sullivan Principles, which consisted of various objectives that would help the signatories work toward economic, political, and social justice.18

Students immediately reacted by building six “shanties,” constructed of wooden planks, chicken wire, and cardboard, outside of Bristol Center to symbolize African poverty. Twenty-five students spent a night in the shanties amidst the snow, which The Spectator described as a “blizzard that closed all local schools.”19 An all-day teach-in run by Hamilton Organization for Peace on Earth (HOPE) was held in Bristol so that it could coincide with the Board of Trustees meeting on the third floor. The teach-in began at ten in the morning and by the afternoon, there were around 300 students there. A total of over 500 students attended the event, including five students from Colgate. Besides speeches from professors, there was also a musical interlude and a representative from the African National Congress (ANC) Mewli Mzizi who spoke about ANC and its formation.20 Members of Hamiltonians Against Divestment passed around flyers that answered divestment questions to the crowd. The last speaker, Assistant Professor in Sociology Kenneth Wagner, declared, “‘Hamilton Cool’ has received a blow from which it will never recover.”21

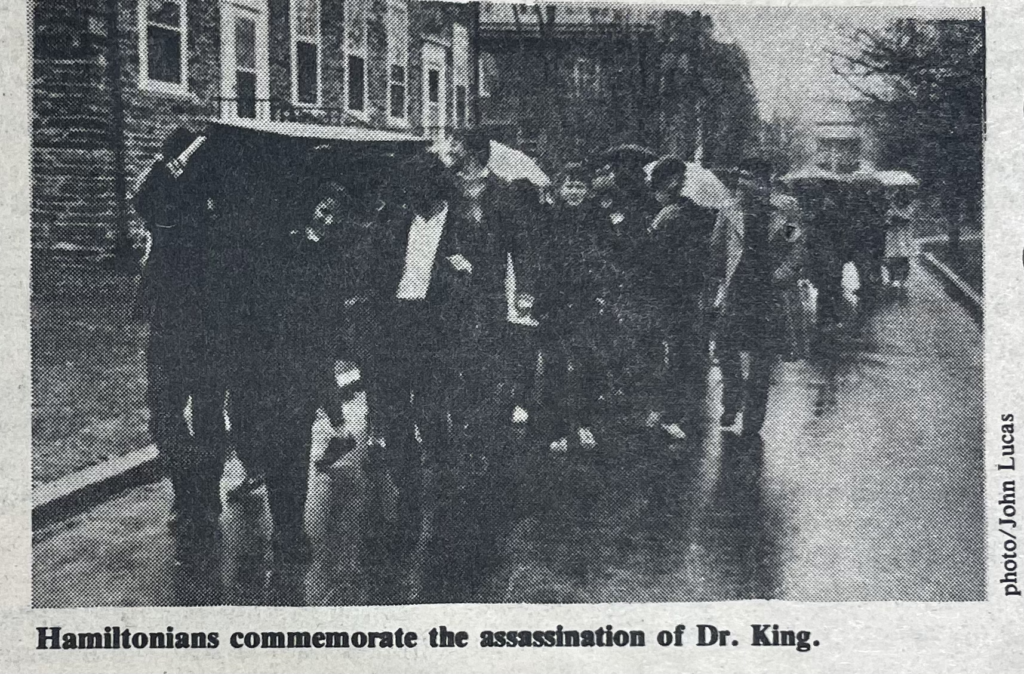

This event began a series of hostile confrontations between the administration and students, who were largely supported by faculty. On April 4, student protestors held a memorial in memory of Martin Luther King Jr., which was followed by a march and sit-ins in various administrative buildings. Four days later, students held a sit-in in the Admissions Office, which they chose as a location as administration had locked students out of the building the previous Friday in anticipation of the protest. President Carovano met the students at Admissions and told them, “You are unwelcome here,” and stated that administration would take disciplinary action against those who remained.22 After a quick vote, students decided to stay. Carovano then asked them to identify themselves by signing a sheet of paper, which set off a debate among the students about what step to take next. Carovano informed the students that the debate was disruptive to the office, so the protestors resolved to continue the debate later but remain anonymous for the time being.23

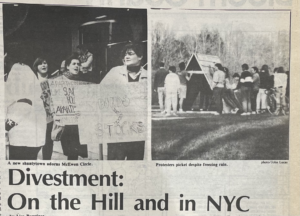

Shortly after, on April 23, four representatives from the Hamiltonians for Divestment met with the Investment Committee of the Board of Trustees at 3 World Trade Center. 60 additional members traveled to New York to picket in the rain, chanting “Divest Now” and “praying.”24 Later, by voice vote, faculty decided to officially announce its solidarity with Hamiltonians for Divestment.25

Much to their surprise, student protestors found their shanties being removed on the evening of April 30 and rushed to save them. Physical Plant workers, cheered on by some student bystanders, removed the shanties surrounding the Alexander Hamilton statue, the Afro-Latin Cultural Center, and were in the process of removing the shanty by McEwen Circle when fifteen student demonstrators locked arms and encompassed one of the last standing shanties. As a crowd of students watched, a Plant worker managed to enter the shanty and began to “swing his sledgehammer” to destroy the structure.26 Though the worker called out a warning every time before he swung, he still managed to injure several students in the process. Administrators on site called the Plant workers away to prevent further injury. According to The Spectator, the Health Center refused to disclose the number or the nature of the injuries.27 A stray student tried to dismantle the damaged shanty but was quickly escorted away by students and faculty. By 9:15pm, 120 protestors had gathered and moved the shanties back to the Alexander Hamilton statue, where a crowd of bystanders mocked the protestors and announced they did not want the shanties on Hamilton property. Most students stayed the night in the shanties, and the next morning, on Thursday, they voted to build a new one by the statue. In the late afternoon, administration requested to meet with eleven members of the group and two faculty members, Professor of Religious Studies Ben H. Ramsey and Professor of Comparative Literature Peter J. Rabinowitz, at Buttrick, where they were handed a preliminary junction by Hamilton’s lawyer. Midnight on Friday, Dean Endy met with over 100 protestors to work out an alternative to police action. At 9:30am, students delivered a new compromise to Dean Endy and President Carovano which included the following: (1) twenty-four hour protection of shanties until Alumni Weekend, (2) the removal of the temporary restraining order and court injunction, (3) a promise to not pursue disciplinary actions for previous actions, (4) increase the number of representative on the Committee on African American studies, (5) ensure that students could speak to trustees at their next meeting, and (6) that they would vote again on the divestment issue. Except for the first two points, the administration accepted the demands. Eventually, students and administrators worked out a compromise that shanties by the statue would be taken down and not placed elsewhere and that the structures could be set up during Commencement Weekend and Alumni Trustee Weekend with the College’s protection.28

The next semester, in fall of 1986, the Hamiltonians for Divestment appealed to the Investment Commitee of Board of Trustees with a new proposal based on Reverend Leon Sullivan’s call for total disinvestment if South Africa’s apartheid system had not changed by May 31, 1987. Because in March, the Board selectively invested in companies based on companies that were signatories of the Sullivan Principles, students thought that the Board might alter their decision from the spring after Sullivan’s new announcement. Unfortunately, the Board turned down the students’ proposal. The October 3, 1986 issue of The Spectator declared disappointedly that “Colgate, SUNY, Columbia, Georgetown have divested, Amherst has agreed to Sullivan’s deadline, and it just looks like Hamilton is going to be the last one around.”29

That month, a federal judge ruled that anti-apartheid demonstrators at the University of Utah do not have take down their shanties despite the fact that they had become insurance hazards for colleges and a target for vandals, which the student demonstrators blamed on conservative students. At various universities across the country, including Berkeley, Stanford, Yale, Dartmouth, North Carolina, and Indiana, shanties had been the target of BB guns, eggs, chemicals, tear gas, and Molotov cocktails.30 At Hamilton, the administration threatened to take legal action if students did not remove the shanties, but, through a compromise, students deconstructed the shanties only to rebuild them during Commence and Alumni/Trustee Weekends.31

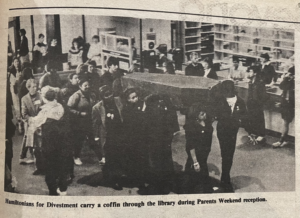

During Parents’ Weekend late October, Hamilton students planned their largest and arguably most dramatic protest that year. Approximately 150 students, faculty, and parents participated in the demonstration which included a funeral procession through Burke Library and a service outside.32 During the procession, students carried an empty coffin “to represent South African funerals in which individuals are presumed dead when no word is heard of them after their imprisonment” while singing “We Shall Overcome.”33 Religious Studies professor Ben Ramsey gave a memorial speech for the service outside, which was followed by a mock slaughter of protestors by students dressed as security forces. Charlie Hartness, Class of 1988, stood among among the “dead” and, assuming the anthropomorphic role of Death, explained to parents that massacres like the fake one just acted out could occur at any time in South Africa and requested parents to write to the trustees to help “break the ties of [Hamilton] college with death.”34

In the newspaper, the divestment debate was lively, with students submitting op-eds both writing for and against divestment. Soon, this debate was taken to the chapel, with President of Root-Jessup Scott Fisher moderating a debate between team anti-divestment, President Carovano and a former resident of South Africa Ezra Kopelowitz, Class of 1988, and team pro-divestment, Philosophy professor Rick Werner and Hamiltonians for Divestment Member Brad Albert, Class of 1988. Carovano stated that he would not only continue to support the trustees but that he had personally arrived at his decision after finding arguments for divestment both “inadequate and unconvincing.”35

The divestment issue exploded on Wednesday, November 12, 1986 with an all-night sit-in in Buttrick hall that ended with twelve Hamilton students suspended. In addition to the apartheid in South Africa, students were also protesting recent racist incidents on campus. The next day, four faculty, seventeen students, and several unknown others were issued a temporary restraining order and banned from disrupting college property and order. Friday morning, Dean of Students Jane Jervis threatened to suspend those still in the building. Twelve students and one alumnus stayed. The students were immediately suspended and given 48 hours to leave campus until May of the following year. On Monday, over one hundred faculty and students gathered to protest the suspension of what became known as “The Hamilton Twelve.”36 The suspension of the Hamilton Twelve created tense controversy on campus. According to On the Hill, “the campus was more divided than at any time since its near-collapse under President Henry Davis in the 1830s.”37 On November 19, exactly a week after the incident, faculty gathered to meet in the Science Auditorium to discuss the Buttrick sit-in and its ramifications. Unexpectedly, student observers showed up to watch the informal meeting, filling up every seat and much of the floor space. A subsequent vote to eject them did not pass the one-third vote. After Dean Jervis gave an account of the event, professors pointed out some missing information in the narrative, namely that (1) the Assistant Dean of Students had personally delivered pizzas to the students, (2) Campus Security didn’t warn others that Buttrick was closed unlike the previous time, (3) administrators had foreknowledge of the protest but did not lock the doors as they did with the Admissions Office the previous spring, and (4) questioned the surveillance during the protest, as administration had not taken footage of other disruptive events.38

Letters in support of the students flooded The Spectator, students wrote several op-eds, and The Spectator wrote an editorial as well. Notably, a letter even came in from the students, staff, and faculty of Antioch College who wrote that they “support[ed] the students of Hamilton College in their right to discuss and protest the problems on their campus with their college administration.”39 The letter gained over 166 signatures from students, faculty, various administrators, including the Provost, Dean of Students, and Associate Dean of Students, and one Oberlin student.40

The Hamilton Twelve did not wait idly to come back to campus. On November 6, 1986, they filed a lawsuit against the College on the basis of three legal claims, one of which included racial discrimination.41 The suspended students claimed that their punishment was more severe in comparison to others who violated campus rules because the Hamilton Twelve were “black or involved in the sit-in,” citing incidents such as shanty demonstrators who were harassed by anti-divestment students and Black students who received death threats that the College never fully investigated.42 Professor Peter Rabinowitz also noted how students involved drinking-related incidents, which included incidents of vandalism or violence, were handed less severe punishments as well.43 On December 23, the Federal District Court dismissed the claims but concluded it did not have federal jurisdiction. The students then appealed to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. On January 30, 1987, the Court of Appeals permitted students to continue their studies until the final ruling.44 The Court ruled that the students were entitled to a trial and pre-trial discovery on July 21 and gave students the right to present their discrimination claim.45 The College requested the Appeals Court for a rehearing, which was granted on October 2. Finally, on June 28, 1988, the Court of Appeals dismissed the students’ claims.46 By then, the Hamilton Twelve had either already graduated or dropped out.47

A few months after over 400 students signed a petition requesting Carovano’s resignation, Caravano announced that he would step down at the end of the 1987-88 academic year.48 Though he claimed that he had been thinking about leaving the job for awhile and that it had nothing to do with the anti-apartheid protests and student lawsuit, Professor Peter Rabinowitz thought otherwise.

“There was one major Appeals Court decision that Hamilton lost very very badly and within a day or two after that decision Carovano resigned,” Rabinowitz said. “He didn’t say he resigned for that reason but that’s pretty much what it was […] The lawsuit continued, there was then a decision that was actually more favorable to Hamilton, but at that point we had a new president who decided that he did not want this whole thing continuing, so he retroactively—I guess, it’s a long time ago—unsuspended everybody at that point.”49

During the lawsuit process, students continued organizing protests, largely with the help of the Coalition Against Racism and Apartheid (CARA), continuing the anti-apartheid activism from the previous years. On November 13, 1987, students assembled a “speak-out” in front of Buttrick where students and faculty jointly spoke out for divestment. Afterwards, students held a march throughout various administrative buildings on campus, singing and chanting throughout.50

On November 20, 1987, CARA organized their first-teach-in. Students and professors spoke about the continued conditions of apartheid, the importance of divestment, the importance of listening to Black South Africans, and raising up the issue of racism at Hamilton.51

After Carovano resigned, CARA’s activism did not halt. In the spring of 1988, members of the organization placed crosses around campus that had names of dead South African detainees or disbanded peaceful protests groups written on it. The purpose of the names on the crosses and the event was twofold: to increase awareness both political activists that had died in South Africa and peaceful organizations had been banned in the country and to stir up the campus right before Trustees Weekend so that the trustees could continue thinking about the issue of divestment.52

While the fight against apartheid was motivated by a real interest in South African policies, concern and resentment over fraternities and racist incidents were also underlying motivators in many of the demonstrations.53 The issue of racism at Hamilton had been slowly bubbling all decade. Though racism was not new to Hamilton, students could no longer ignore it. Perhaps the increasing, though still insubstantial, number of minorities, especially Black students, enrolled at the school combined with racial tensions increasing during the apartheid protests culminated in campus’ need to confront race relations.

“Everything affects you, not just the overt. Subtle things really hurt, too. I’m more scared of the person who is unconsciously racist.”

– Black woman as quoted in The Spectator, February 20, 1987

A Black student revealed that during the shanties demonstration, she had heard people yelling the racial slurs, shouting “We don’t need you n*****s here,” and had personally received a phone call from someone who said, Third World n****r go home.”54 Another Black student told The Spectator that she had been getting death threats from both men and women through the phone since coming to Hamilton three times a day, with callers threatening that they would “lynch, kill, or rape her.” She said she knew they watched her because they would tell her what she had been wearing that day.55 A Hispanic student also shared how he was harassed “physically, emotionally, and verbally,” citing an incident near Bundy where he and his friends were called “third world mother fuckers” and almost run over by a fraternity member because he thought they had slapped his car.56 One student summarized her fear over both overt and more covert racism:

“We’re not dealing with crosses on the lawn,” she said. “Stereotyping […] is so easy. In class, whenever black culture is discussed, everybody turns to look at the black person. People meet me for dinner and only want to talk about my blackness. It makes you feel socially outcast — people only notice your differences […] Everything affects you, not just the overt. Subtle things really hurt, too. I’m more scared of the person who is unconsciously racist.”57

Dean Jervis guessed that, not including telephone calls, twenty racist incidents had occurred in the past year. In response to campus racism, the College created a Racial Grievance Board first suggested by Hamiltonians for Divestment the previous March.58 The College also decided to hold a Prejudice Reduction Workshop run by three consultants from the National Coalition Building Institute (NCBI) open to faculty, administration, and students.59

Hamilton’s habit to take “two steps forward, one step back” throughout its history is due in part to the large presence of fraternity culture on campus and social life. The racist, sexist, and homophobic history of American fraternities has been well-documented; a quick Google search will reveal a plethora of results. Randolph Splitter, Class of 1968, remarked on how fraternities had “dominated” Hamilton during his era and that it was “the worst possible everything—toxic masculinity—that you could imagine. It was all true and all there in the fraternities.”60

Isserman added, “White fraternities in particular serve as places that license bad boy behavior … Black fraternities and sororities are more mutual aid, looking out for people, seeing if they need loans to buy, and so on and so forth, being a kind of support group. If white fraternities, sororities, but fraternities in particular, if that’s what they did, I’d have no objection to them, but that’s not what they do.”61

Isserman speculated that fraternities would be “gone in ten years because you can’t build a diverse enough student body around a campus culture that still has a strong Greek element to it.”62

Although the focus in the eighties was not on Asian/Asian American issues, the tumultuous decade paved the way for the construction of the East Asian Language and Literature program, which was first constructed in the 1990-91 academic year, through students’ fight for an Africana studies program. In addition, the question of diversity and representation is one that Hamilton still tries to address today. Hamilton College’s website has a “Diversity, Equity & Inclusion” page that states their commitment “to work against systemic racism and bigotry,” their acknowledgement that “inequity” exists on campus, and a list of steps the College is actively taking to create an inclusive community.

How the legacy of the eighties will impact Hamilton is yet to be determined. Will students return to the “Hamilton cool” and raucous, uncouth behavior or engage in activism, protests, and the continual fight for equality?

Notes

1. Maurice Isserman, interview by Rachel Lu, August 4, 2021, Clinton, NY.

2. Isserman, interview.

3. Maurice Isserman, On the Hill: A Bicentennial History of Hamilton College, (Clinton: Trustees of Hamilton College, 2011), 260.

4. Stephen Pratt, “Faculty attitude questioned,” Hamilton College Spectator, April 12, 1986, 18.

5. Pratt, “Faculty,” 18.

6. Kirk Perry, “Why no Afro-American Studies?,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 9, 1985, 22.

7. “Spectator interview series with professor, trustee and president,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 15, 1985, 16, 19.

8. “Spectator interview series,” 16, 19.

9. “Spectator interview series,” 16, 19.

10. “Spectator interview series,” 16, 19.

11. “Integrity in the College Curriculum: A Report to the Academic Community. The Findings and Recommendations of the Project on Redefining the Meaning and Purpose of Baccalaureate Degrees,” Association of American Colleges, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed251059.

12. Kanchalee Svetvilas, “American Association of Colleges recent advisory report,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 15, 1985,15.

13. Lea M. Haber, Editorial, Hamilton College Spectator, 1987.

14. Isserman, interview.

15. In an email correspondence with Edward North Chair of Classics and Professor of Africana Studies Emerita Shelley Haley, she mentioned that interdisciplinary program which was called “Afro-American Studies” at the time was created around 1985 or 1986.

16. T.A. Tuck, “Admissions recruits for diversity,” Hamilton College Spectator, October 4, 1985, 5.

17. Douglas Hsiao, “Admissions seeks diversity,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 15, 1985, 3.

18. Lea Haber and Meg Gates, “Trustees say “NO!,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 10, 1986, 1.

19. Meg Gates, “Hub Teach-in,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 14, 1986, 3-4.

20. Led by Nelson Mandela, the African National Congress was recognized as the most powerful Black political organization in South Africa. Today, it remains a social-democratic political party in South Africa.

21. Gates, “Hub Teach-in,” 3-4.

22. Meg Gates, “Carovano Threatens Protestors,” Hamilton College Spectator, April 11, 1986, 1, 6.

23. Gates, “Carovano Threatens Protestors,” 6.

24. Lisa Burstiner, “Divestment: On the Hill and in NYC,” Hamilton College Spectator, April 25, 1986, 7.

25. Burstiner, “Divestment,” 7.

26. D. Desantis et al., “Divestment explodes,” Hamilton College Spectator, May 2, 1986, 1, 7.

27. Desantis et al., “Divestment explodes,” 1, 7.

28. Desantis et al., “Divestment explodes,” 1, 7.

29. Richard Larson, “Trustees say no again,” Hamilton College Spectator, October 3, 1986, 3.

30. “Judge says shanties will stand,” Hamilton College Spectator, October 3, 1986, 9.

31. Isserman, On The Hill, 327.

32. Cathlin Baker, “Divestors bring plea to parents,” Hamilton College Spectator, October 31, 3.

33. Baker, “Divestors,” 3.

34. Shelly Danse, “Presidents and HFD debate divestment,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 14, 1, 5, 6.

35. Richard Larson, “Protest results in 12 suspensions: Carovano administration under fire,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 21, 1986, 1.

36. Isserman, On the Hill, 328.

37. T.A. Tuck, “Administrators grilled at faculty meeting,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 21, 3.

38. “Letters,” The Hamilton College Spectator, November 21, 1986.

39. “Letters.”

40. Kanchalee Svetvilas, “12 back for now,” Hamilton College Spectator, February 13, 1987, 1, 4, 6.

41. The reason the case ended up going to the federal court was because one of the claims was that the College violated constitutional due process.

42. Svetvilas, “12 back,” 1, 4, 6.

43. Svetvilas, “12 back,” 1, 4, 6.

44. Kanchalee Svetvilas, “Students’ case still held up in Appeals Court,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 13, 1987, page 9.

45. The students’ discrimination claim alleged that Hamilton punished the sit-in protestors more severely because of their race or their stance as protestors in comparison to other incidents, such as Hamilton’s failure to punish or punish to the same extent students who made death threats to Black students, serious hazing injuries, and rape cases.

46. “Braden L. Albert, Francis J. Callard, Julie L. Jones, Gurmelamede, Molly Mysliwiec, Demetri Orlando, Michellepaninos, Cathleen Perry, Amy Rozgonyi, Gregory Shin, Michaeltilman, and Johnette Traill, Plaintiffs-appellants, v. J. Martin Carovano, President of Hamilton College; Jane L.jervis, Dean of Students at Hamilton College; Andhamilton College, Defendants-appellees, 851 F.2d 561 (2d Cir. 1988),” Justia, accessed August 12, 2021, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/851/561/320508/.

47. Isserman, On the Hill, 327.

48. Isserman, On the Hill, 328.

49. Peter Rabinowitz, interview with Rachel Lu, August 12, 2021. Zoom.

50. Lynne Degitz, “Activism returns,” Hamilton College Spectator, November 20, 1987, 1.

51. Lynne Degitz, “CARA teach-in,” Hamilton College Spectator, December 4, 1981, 4.

52. Liza McDonalds, “Students Press for Divestment,” Hamilton College Spectator, March 4, 1988, 1.

53. Isserman, On the Hill, 327.

54, Rich Larson, “Harassment Board Created,” Hamilton College Spectator, February 20, 1987, 1, 3, 5.

55. Larson, “Harassment,” 1, 3, 5.

56. Larson, “Harassment,” 1, 3, 5.

57. Larson, “Harassment,” 1, 3, 5.

58. Larson, “Harassment,” 1, 3, 5.

59. Monique Lui, “Community Takes On Prejudice,” Hamilton College Spectator, February 20, 1987, 1, 5.

60. Randolph Splitter (Class of 1986), interview by Rachel Lu, August 3, 2021, Zoom.

61. Isserman, interview.

62. Isserman, interview.

“Before We Assume”: The Effect of 9/11 on Hamilton’s Campus

By Rachel Lu

“I thought that perhaps Hamilton students would rise above such ignorance and hatred, which only help to spread fear and violence. I was wrong. People I have come in contact with have been quick to condemn Muslims, to attack their culture and way of life as somehow being linked intrinsically to violence, terrorism, and abuse of women.”

– Joe Livingston, Class of 20021

The early 2000s saw a continued investment in talking about diversity and raising race awareness. Maurice Isserman, Publius Virgilius Rogers Professor of American History, determined the 2000s as another turning point for Hamilton. He commented on the decline in vandalism, tamer fraternities, a cleaner campus, and, most importantly, a student population that finally tipped majority female, creating an atmosphere of caring more about academics.2 Isserman mused, “[M]inority enrollment, maybe Asian American enrollment—I don’t say this with any evidence—but my guess is that just as Hamilton began to attract more women in a post residential fraternity era, that may have been a factor in making it more attractive to more diverse group of students.”3 The confrontation with racism came to a peak post 9/11 with students calling for peace and urging others to not stereotype Muslims or those of Arab descent. Across America, South Asians and Sikhs also became the victims of hate crimes and racist harrassment because they were mistaken for Muslims and/or Arab Americans. According to Sangay K. Mishray, “South Asians straddled the attributes of model minority and perpetual outsider that defined their position in the racial order” after the 9/11 attacks.4

The dialogue surrounding race was not always a comfortable one though. In preparation for Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum’s visit to Hamilton College, many students endeavored to read her book but quit halfway because they were upset or could not relate to the criticism inside. Tatum’s talk on racism as a system of advantage left many white students unsettled, especially the discussion on how even non-actively prejudiced students were racist because they benefited from their whiteness. After her visit, Hamilton students and faculty formed a “white discussion group for students concerned with diversity and racism on campus” to continue digesting the points Tatum raised and to further discuss race relations.5

Late into 2000, several students expressed their thoughts on race on campus through The Spectator, sharing how the majority of students seemed to have a complete lack of awareness on the issues that students of different races and backgrounds face.6 One male student wrote, “I know there are schools where you don’t have to be afraid of being assaulted on paths and where race and sexual orientation are never issues.”7

On August 3, 2001, President Eugene M. Tobin delivered a speech during Hamilton’s Convocation Ceremony urging for the various groups in the student body to interact with one another. His speech followed what The Spectator noted as “a year marked by several acts of hate.”8