Thanks for a great semester guys! I hope you all have an excellent summer! ☀

Author: mbuiocch

The Failure of VR

As an avid and only somewhat pretentious film buff, I was more than ready to dive into the supposedly immersive world of experimental French cinema with La Jetée. While watching the film, however, I felt underwhelmed. During this course, we cultivated and formed a clear picture of what a virtual reality should entail–to me, this mainly translates to the ability of an artificial world to reproduce sensory and emotional characteristics found in reality. The way that Chris Marker directed his film and his choice to frame the film through photographs rather than animated scenes lends nothing to this definition. Instead of flowing through the motions of the protagonist’s dreams, the journey from the past to the present and to the future felt stagnant and clenched. The whispered voices and ambient noise definitely created a sense of discomfort, but the sequential photographs quickly drew me out of the film’s world.

I guess this took a more critical tone that I usually use in my blogs (way to end the year!), but I guess it begs an overarching question: did you feel that La Jetée created a successful virtual reality? What is necessary to create a virtual reality? What’s left when a virtual reality is deemed unsuccessful? And, since the film’s story specifically centers on the memories of one man, is the disjointed reality created in the film meant for the viewer or for the protagonist?

Adam and Eve in Anti-Gone

I love a story that both grabs and confuses my attention. As a result, I found Anti-Gone abstract, unsettling, and fascinating. Mainly, I became intrigued by Spyda and Lynxa’s journey among their world’s vast emptiness. While reading the graphic novel, it was impossible not to find similarities between the isolated Spyda and Lynxa and Adam and Eve, another more noteworthy stranded couple. Willumsen fills his story with symbols representative of temptation, enlightenment, and confusion that similarly appear in the original creation story. Spyda and Lynxa’s evacuation from the island after having sex mirrors Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Paradise. While Adam and Eve realize their sins, however, Spyda and Lynxa continue their lives as they had before arriving on the island and display a lack of regret/recognition for their actions. Spyda and L ynxa continue to drift through their abstract and often confusing world in search of indulgent experiences, like shopping and drugs. As a result, while Spyda and Lynxa resemble their biblical counterparts, they do not necessarily follow the creation myth. While Adam and Eve successfully birth a new human civilization and act as humanity’s paternal guardians, Spyda and Lynxa remain much more selfish. They focus on creating new experiences for themselves rather than others. Therefore, Willumsen’s creation story differs from the original story because it focuses on selfish rather than selfless creation.

Mind Morphing

Offred’s narrative surprised me when she mentioned her encounter with Japanese tourists while running errands with Ofglen. This is my second time reading this novel and, despite my memory and the numerous adaptations of the novel onto the big and small screen in recent years, I always seem to forget that there exists a world outside of the strict oligarchy of Gilead. This scene makes the novel all the more heartbreaking, knowing that, if Offred did not live where she did, she might have escaped her demeaning fate and enjoyed a long, happy life with Luke and their daughter.

The scene also reveals the complexities of Offred’s mentality and perspective after immersing herself in Gilead society. While Offred acknowledges and envies the tourists’ freedom to dress without regulations, she also feels disgusted by their short skirts, high-heeled shoes, and uncovered heads “in all [their] darkness and sexuality” (28). Offred’s dystopian world has not only destroyed her autonomy as a American citizen, but also her ability to perceive appearance and freedom without the dogmatic influence of Gilead rules. If a person’s perception of reality is based on their ability to perceive through senses and the mind, it seems clear that Offred’s confused, alternating mental state (wanting freedom while also judgment of people with freedom) functions as a result of her abrupt change in reality.

Can we forgive Offred for her temporary lapse in behavior? Is she a reliable narrator who opposes Gilead’s structure, or is she an unreliable narrator for unconsciously supporting and becoming complicit to Gilead’s rules?

Based on a True(ish) Story

As a fan of Shakespearean comedies, I loved how Gaiman weaved the characters and literary criticisms of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” into his own graphic retelling of the play. Mainly, I loved the commentary and corrections from the Fayes as they witnessed Shakespearean’s reinterpretation of a “real” event that occurred in their realm. Gaiman converges two different interpretations of reality and fiction into one scene. For Shakespearean and his players, their reality focuses on the success of their fictitious, fantastical comedy. For Titania, Auberon, and other members of the Fayes, their reality mirrors Shakespeare’s seemingly absurd and comedic play (although Shakespeare’s work does take a few creative liberties). These two perceptions of reality clash throughout Gaiman’s story, as the players grow fearful of their magical, otherworldly audience and members of the Fayes, especially Puck, become increasingly more frustrated with their portrayals onstage until they take direct action. Gaiman masterly expands the motif of reality versus fantasy originally in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” to show the often tense convergence between fiction and real life.

As someone who likes to dissect literary criticisms of Shakespearean plays, Gaiman’s idea of reality versus fantasy struck out to me. In a fictitious text, how does a reader determine whether a interpretation of the piece is true? What is necessary for a fictitious text (even if it contains fantastical elements) to feel true?

The Sound of Silence

While reading “Calliope” and “A Dream of a Thousand Cats” for today’s class, I was awestruck by the illustrators’ ability to elicit sound from inanimate panels and images. Like I mentioned in class, the panels towards the end of “Calliope” gave off a cacophonous, irritating buzzing, as Richard loses his mind and Oneiros slips from the pages of the story. Oneiros’s speech bubbles, a constant throughout each volume of The Sandman, shows off his gravely, discorded voice. Even in “A Dream of a Thousand Cats,” the speech bubbles of the cats, with their disjointed tails, make their words sound whispered and faint. It’s incredible to me how these illustrations, which are naturally silent, can manipulate the mind into hearing sounds that do not really exist. In this way, the panels and speech bubbles create a virtual soundscape for readers.

The idea of sound also plays major roles in both of Gaiman’s stories, as both “Calliope” and “A Dream of a Thousand Cats” highlight victimized protagonists. Calliope’s abuse and entrapment, which silences her voice and restricts her free will, grants a level of tragic irony to the story, as she is famously known as the Muse with “the beautiful voice.” The main cat in the second story, unable to communicate with the human world, undergoes torture and grief after the murder of her litter. Both Calliope, a malnourished, distorted, and real form of a mythical creature, and the cat, an animal with the incredible gift of human sentience, serve as victims in their stories and fantastical beings that do not exist in reality. Why do forces of reality silence these characters? And do they regain their voices? Why is sound so crucial to the creation of reality?

Where is the Island?

While finding inspiration for this week’s blog post, I stumbled upon an interesting fact on The Invention of Morel‘s Wikipedia page. The section “Plot Introduction” states that “A fugitive hides on a deserted island somewhere in Polynesia. Tourists arrive, and his fear of being discovered becomes a mixed emotion when he falls in love with one of them. He wants to tell her his feelings, but an anomalous phenomenon keeps them apart.” Now, like other students, I am against using Wikipedia as a source, and was actually trying to find some scholarly articles on the novel by way of the page’s cited sources. Yet, this sentence stumbled me, mainly because I had read the book thinking the island had no clear location. As a reader, it is more interesting and fitting with the mood of the book to imagine the island as completely isolated and removed from reality–this explains the mystical, sci-fi like elements that happen once Morel reveals his invention, and also adds to the creepy, abandoned feeling that permeates the entire island. The perceived, Polynesian location of the island removes that fantastical, mysterious element, but gives the story more of a realistic grounding. In your opinion, does it matter if the island has an actual location or not? If the island is indeed in Polynesia, how does that new location help the mysterious, non-realistic elements of the novel? Where do you think the island is located?

Flying Glass Bottle

Model of a flying glass bottle seen at the end of Alice’s coronation dinner in Through the Looking Glass. Enjoy!

Can Unity really be reality?

Today, our group enjoyed the multitude of assets and design elements within Unity. We played around with different prefabs, researched new environmental designs, and added interesting and occasionally ridiculous assets to our barren virtual world (Did you know you could add a free digital rubber horse mask? Everyone should check that out–it’s incredible and incredibly absurd.). While we discovered more of Unity’s new and exciting design elements, we encountered some logistical issues when one of my group members attempt to pick up an arrow to shoot at a target during a VR demonstration. When we asked Ben how to pick up objects, he said that the program did not support tactile actions and that another program had to be installed in order to allow the user to pick up and touch objects. Ben, along with Professor Serrano, added that the ability to touch objects was not required in the original project outline. This notion seemed contradictory to the intentional of creating a virtual reality. As we discussed earlier this semester, our interpretation of reality relies on our sensory perceptions, including the ability to touch and feel objects. Without the ability to touch and directly interact with the objects in Unity environments, the virtual reality appears more like a stagnant museum exhibit. Of course, this information is based on my own interpretation of what reality entails.

Can a user be fully immersed in a Unity reality even if he/she cannot sensorially interact with the environment? And, if the environment cannot replicate the sensation of touch, what can Unity allow instead that still contributes to the user’s sensory experience in VR?

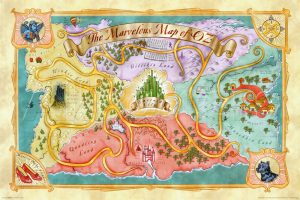

Regionality in Oz

The World of Oz stems far beyond Baum’s original vision in his 1900 novel. In his next thirteen books in the Oz series, Baum expanded his original vision by introducing his readers to new characters that inhabited new realms outside of the Emerald City and the surrounding Munchkin, Gillikin, Winkie, and Quadling Lands. In recent memory, other authors, such as Gregory Maguire in his Wicked Years series, have stretched out Oz’s borders past Baum’s original vision. Oz is innately vast and diverse, yet I was surprised to discover the close-minded and often xenophobic regionality that permeated the end of the novel, as Dorothy and her friends venture to find Glinda. When the Monkey King returns to Dorothy, who requests a safe voyage back to Kansas, the King refuses, reasoning that “there has never been a Winged Monkey in Kansas yet, and I suppose there never will be, for they don’t belong there” (213). The doll that Dorothy and her entourage encounter in the China Country voices a similar sentiment when she claims that when dolls are taken from the country their “joints at once stiffen,” and they “can only stand straight and look pretty,” thus losing the ability to speak and move (234). The strict regionality seemingly opposes the “Americanness” of the novel and contradicts Dorothy’s innate motivation to explore Oz in the name of “Manifest Destiny.” The politics and culture around the time of the novel’s publication, however, might explain the inherent resistance to travel and xenophobia in Oz. The Monkey King’s claim that he belongs to a specific land resonates with the archaic and racist ideas that white people (not Indigenous Americans) belong in North America (a sentiment voiced by Baum in many political editorials) and that, following the emancipation of slavery and the birth of the Reconstruction Era in the 1870s, African Americans should return to their home country. The regionality in Oz also speaks to the issue of state rights in the USA as well as the emerging idea of the “nation state,” which would gain more recognition nineteen years after the publication of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz during the Treaty of Versailles. What does Baum’s use of clear borders, regions, and subtle xenophobia try to treat young readers? Are these themes American or anti-American?

The World of Oz stems far beyond Baum’s original vision in his 1900 novel. In his next thirteen books in the Oz series, Baum expanded his original vision by introducing his readers to new characters that inhabited new realms outside of the Emerald City and the surrounding Munchkin, Gillikin, Winkie, and Quadling Lands. In recent memory, other authors, such as Gregory Maguire in his Wicked Years series, have stretched out Oz’s borders past Baum’s original vision. Oz is innately vast and diverse, yet I was surprised to discover the close-minded and often xenophobic regionality that permeated the end of the novel, as Dorothy and her friends venture to find Glinda. When the Monkey King returns to Dorothy, who requests a safe voyage back to Kansas, the King refuses, reasoning that “there has never been a Winged Monkey in Kansas yet, and I suppose there never will be, for they don’t belong there” (213). The doll that Dorothy and her entourage encounter in the China Country voices a similar sentiment when she claims that when dolls are taken from the country their “joints at once stiffen,” and they “can only stand straight and look pretty,” thus losing the ability to speak and move (234). The strict regionality seemingly opposes the “Americanness” of the novel and contradicts Dorothy’s innate motivation to explore Oz in the name of “Manifest Destiny.” The politics and culture around the time of the novel’s publication, however, might explain the inherent resistance to travel and xenophobia in Oz. The Monkey King’s claim that he belongs to a specific land resonates with the archaic and racist ideas that white people (not Indigenous Americans) belong in North America (a sentiment voiced by Baum in many political editorials) and that, following the emancipation of slavery and the birth of the Reconstruction Era in the 1870s, African Americans should return to their home country. The regionality in Oz also speaks to the issue of state rights in the USA as well as the emerging idea of the “nation state,” which would gain more recognition nineteen years after the publication of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz during the Treaty of Versailles. What does Baum’s use of clear borders, regions, and subtle xenophobia try to treat young readers? Are these themes American or anti-American?