I found this poem particularly interesting because of its autobiographical nature. “Indian Woman’s Death Song” conveys the narrative of a mother abandoned by her husband, who had left her for another wife. Interestingly enough, Hemans herself was a mother of six that was deserted by her husband for another woman. In a way, Hemans uses the Native woman to avenge the happiness stolen from her–by her own husband–as she cannot do so herself. Furthermore, Hemans uses the outcast and abandoned Native woman to underline the issue of female segregation within culture and society due to man-made manacles. In this way, Hemans draws attention to her own plight as an outcast and as an abandoned wife and mother. Hemans garners empathy from readers early on in the work through the implementation of the introductory note, in which she describes the Native woman as “[a]n Indian woman, driven to despair by her husband’s desertion…” Through conveying the despair of a woman over her trivial and seemingly unimportant position as one of her husbands many wives, Hemans opposes and criticizes the objectification of women as inhuman, emotionless objects meant to endure the whims of men. Like Hemans herself, who began writing to support her children after the desertion of her husband, the Native mother takes her fate into her own hands as an active and living woman, rather than remaining passive, desperate, and helpless.

Author: Taylor Santulli

Barbauld’s children’s books

Prior to our last class, I do not recall having heard about Barauld or having read any of her work, but I found it particularly interesting that she was also a children’s author. One of the children’s books that I found was Lessons for Children, written in 1778 after Barbauld and her husband founded their own academy, the Pelgrave School. Lessons for Children urges children to explore the world around them and is modeled after a mother teaching her son; it was based off of Barbauld’s methods of teaching her nephew and adopted son, to read. Lessons for Children was groundbreaking at the time, having bee the first educational work aimed at younger readers to move away from abstract and moral concepts. Learning was made effective by the introduction of ideas and actions relating to every day objects and activities that would have been familiar to an 18th century child. Lessons for Children was also ground breaking in the way that it was printed. Barbauld insisted that the book be printed in large type with large margins, so children could easily read them; this made Barbauld the possible originator of this practice. Lastly, these production changes made the books expensive, too expensive for poor children. Thus, Barbauld’s books widened the education disparity between poor and middle-class children, helping to create a distinct aesthetic for middle-class children’s books.

https://archive.org/details/lessonsforchild00barbgoog/page/n6/mode/2up

“So we’ll go no more a roving”

“She Walks in Beauty”

“She Walks in Beauty” has been one of my favorite poems since I read it in high school. What has always intrigued me about this poem is the multidimensionality of the woman’s beauty. Byron’s description of the woman’s beauty supersedes expectations of receiving shallow and superficial commentary on beauty; like the typical and expected descriptions of long golden hair, rosy cheeks, and fair skin. What makes the descriptions in this poem intriguing is how dynamic the woman’s beauty seems to be. This is evident in Byron’s exploration of her outer and inner beauty. Byron admires the woman’s physical beauty as it is in harmony with her inner beauty and her “heart whose love is innocent” (L18). The poem’s title itself also serves as a testament of the multidimensionality of her beauty. The unusual construction of a woman “walking in beauty” makes her beauty seem more dynamic and remarkable, as it surrounds the woman almost like an aura. She isn’t just an attractive woman, but the living, breathing, “walking” woman that she is is remarkably beautiful.

Through Byron’s usage of contrasts throughout the poem he conveys that her beauty encompasses everything, it is more and less, bright and dark, and it is “all that’s best” (L3). The woman’s beauty itself is that of contrasts: “like the night / Of cloudless climes and stary skies; / And all that’s best of dark and bright,” and she has “raven tress[es]” that contrasts against her presumably fair skin (L1-3 and L9). Despite her beauty being one of contrasts, these contrasts have reached a state of harmony. In this way, Byron suggests that beauty is a kind of perfection that is achieved through the harmony of contrasts. True beauty is the perfect balance of everything.

Question of consent in “The Eve of Saint Agnes”

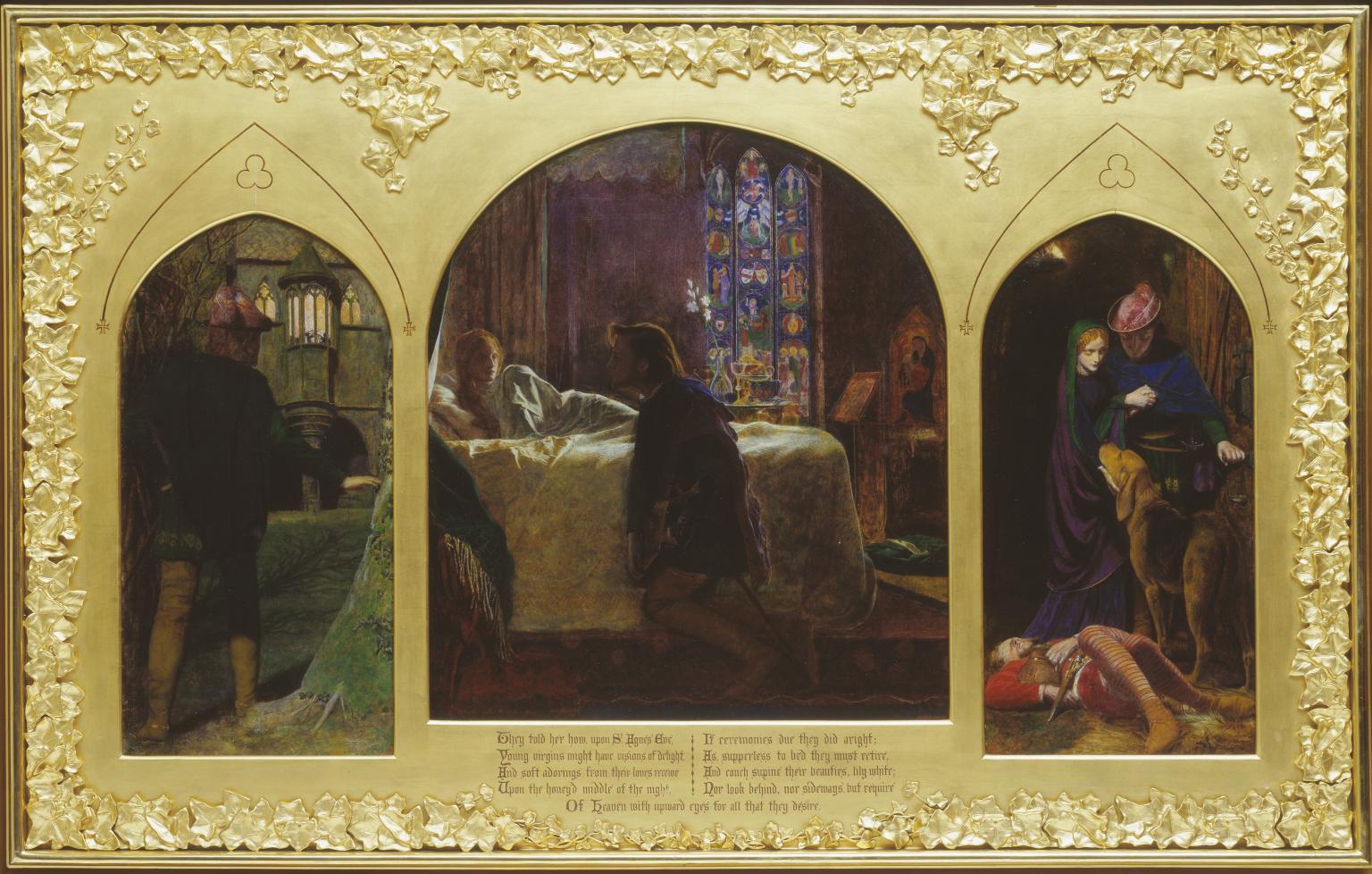

The Eve of Saint Agnes, Arthur Hughes (1856)

Last class, the question of whether or not Madeline was raped by Porphyro arose. I too had found their interaction to be a bit ambiguous, given Porphyro’s creepiness and St. Agnes’ being the patron saint of rape victims. Upon giving the poem a second reading, I believe that the two did have sex and that it was consensual, despite Madeline’s implying that Porphyro was uglier then she imagined. Madeline urges Porphyro to give her back his songs and “immortal looks” (L 313) The following interaction between the pair is then likened to that of flowers: a violet and a rose, producing a “solution sweet” ( L 322). Lastly, at the end of the stanza 36 it states that “St. Agnes’ moon hath set” (L 324). I believe that this means that Madeline’s chastity and virginity is no longer protected or accepted by St. Agnes, whom Madeline had prayed to.

The Death of Shelley

https://wordsworth.org.uk/blog/2014/07/08/full-fathom-five-the-poet-lies-the-death-of-percy-bysshe-shelley/

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45143/the-triumph-of-life

I stumbled across this particularly interesting article about the death of Shelley.The article also reveals issues that Shelley experienced throughout his short life like hallucinations — interestingly, they were frequently about his doppelgänger — and marital issues with Mary Shelley. As mentioned in the article caption, Shelley tragically passed at the age of 29 in a boating accident. Despite the tragedy of his death, Shelley’s passing was poetic in a way; having died as a result of his own folly and possibly hubris, after he refused assistance during a storm. Also, ironically enough prior to his death, Shelley began writing a poem, “The Triumph of Life.” This poem touches upon the exploration of the nature of being and reality, as well as humanity’s victory over nature and the constraints of the mortal existence. Once again, this is ironic as Shelley passed at the young age of 29 during a storm at sea.

Coleridge’s “To a Young Ass”

After Professor Oerlemans had briefly mentioned Coleridge’s works about animals, I was curious and decided to look for them. In doing so, I stumbled across “To a Young Ass”, an odd and definitely unique poem that conveys Coleridge’s sympathy for a donkey foal. Coleridge’s compassion for animals can be compared to Wordsworth’s almost worshipful respect for nature. Throughout the poem, Coleridge pities the foal and its mother’s inability to explore the “land of luxury”. The foal and its mother are an “oppressed race”, forced to meekly await their lives of burden and suffering.

I found this poem interesting because it can be interpreted in a social and religious context. Firstly, the poem can be interpreted as a drawing parallel between the plight of the burdened, starving donkey and the English working class. The life of the trapped, hard-working, and bread eating donkey can be compared to that of the inner city poor people of England during the end of the 18th century. Furthermore, this poem can be interpreted in a religious context as well. Donkeys are symbols of spiritual merit; they are the paragons of patience, humility, lowliness, and most importantly, suffering. These are attributes that earlier Christians believed humans should exude in order to gain eternal life. In order to find favor in heaven, we must bear God’s burdens and suffer in life. In this way, the human-like donkey, a “Meek Child of Misery” with its “languid patience” is deserving of Coleridge’s pity.

Poor little Foal of an oppressed race!

I love the languid patience of thy face:

And oft with gentle hand I give thee bread,

And clap thy ragged coat, and pat thy head.

But what thy dulled spirits hath dismay’d,

That never thou dost sport along the glade?

And (most unlike the nature of things young)

That earthward still thy moveless head is hung?

Do thy prophetic fears anticipate,

Meek Child of Misery! thy future fate?

The starving meal, and all the thousand aches

‘Which patient Merit of the Unworthy takes’?

Or is thy sad heart thrill’d with filial pain

To see thy wretched mother’s shorten’d chain?

And truly, very piteous is her lot –

Chain’d to a log within a narrow spot,

Where the close-eaten grass is scarcely seen,

While sweet around her waves the tempting green!

Poor Ass! they master should have learnt to show

Pity – best taught by fellowship of Woe!

For much I fear me that He lives like thee,

Half famished in a land of Luxury!

How askingly its footsteps hither bend?

It seems to say, ‘And have I then one friend?’

Innocent foal! thou poor despis’d forlorn!

I hail thee Brother – spite of the fool’s scorn!

And fain would take thee with me, in the Dell

Of Peace and mild Equality to dwell,

Where Toil shall call the charmer Health his bride,

And Laughter tickle Plenty’s ribless side!

How thou wouldst toss thy heels in gamesome play,

And frisk about, as lamb or kitten gay!

Yea! and more musically sweet to me

Thy dissonant harsh bray of joy would be,

Than warbled melodies that soothe to rest

The aching of pale Fashion’s vacant breast!

Psychology and Wordsworth

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/out-the-darkness/202004/the-greatness-william-wordsworth

I know we’re a bit past Wordsworth now, but I found this article a few days ago and had been waiting to share it on the class blog. Surprisingly enough, Wordsworth is even relevant in the field of psychology. Steve Taylor–the author of the article–believes that Wordsworth’s works can be viewed through a psychological perspective. Wordsworth’s writing is the paragon of the evolution of the consciousness during the romantic period; previously, poems had a subject, but Wordsworth made the subject the poet. Through works like “Tintern Abbey”, “The Intimations of Immortality”, and “The 1805 Prelude” Wordsworth captures the moments in which our awareness of self becomes more intense; those existential moments where we become aware of our own presence in the world and the ways that we interact with the things around us. In a way, this connects with the discussion that we had in class about our existential childhood thoughts, the moments where we realized–or at least I realized–that I was not a robot. It is interesting to see connections being made between our modern and scientific understanding of the human consciousness and romantic literature.

Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways by Wordsworth

Motion and Means, on land and sea at war

With old poetic feeling, not for this,

Shall ye, by Poets even, be judged amiss!

Nor shall your presence, howsoe’er it mar

The loveliness of Nature, prove a bar

To the Mind’s gaining that prophetic sense

Of future change, that point of vision, whence

May be discovered what in soul ye are.

In spite of all that beauty may disown

In your harsh features, Nature doth embrace

Her lawful offspring in Man’s art; and Time,

Pleased with your triumphs o’er his brother Space,

Accepts from your bold hands the proffered crown

Of hope, and smiles on you with cheer sublime.

As I was flipping through the pages to get to “The 1805 Prelude”, I stumbled across “Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways”, which in my opinion is an odd name for a poem. So of course I read it. “Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways” concerns society’s rapid embrace of industrialization and technology, and the ways that modernization lays opposite to traditional Romantic ideals. Wordsworth begins the poem by conveying the scaring of the natural landscape, the scars that humans have left behind. In this poem, “Nature” is symbolically feminine while technology is a masculine force. Thus, Nature’s feminine and maternal force is no match for the masculine force of industrialism; Nature embraces industrialism’s “harsh features. In a way, I find this poem interesting in relation to Wordsworth’s other works, especially “The 1805 Prelude: Book First” because of the way it portrays human’s interactions with nature. In a lot of the poems we’ve red from Wordsworth, most recently books 1 and 2 of “The 1805 Prelude”, we’ve read about Wordsworth’s escapes into Nature. Him using it to escape the humdrum of city life and return to his child hood. But what about nature’s escape from us? Nature has no means of escaping what we force it to endure. So we as humans, admire its beauty, while simultaneously destroying it with our “steamboats, viaducts, and railways”. So in a way, I found it ironic that Wordsworth writes about escaping into Nature, while Nature has no means of escaping us. Wordsworth’s poem “Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways” shows a different side of nature while also painting a bleaker picture of what Nature is becoming, rather than that of tales of stolen rowboats and night skies.

Nature as religion

When first reading Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey, I was having a bit of difficulty understanding it; it had seemed so dense, verbose, and intimidating. But, after our class discussion, I believe that I have garnered a better grasp on the work. Something that had stuck out to me was Benjamin’s brief comment regarding the Garden of Eden and nature, connecting nature with the Bible. With this in mind, while rereading Tintern Abbey, I noticed that in a way, Wordsworth makes a god out of nature.

In the work, nature exemplifies a god’s omnipresence, omnipotence, and omniscience. Nature displays its power that “impels / All thinking things, all objects of all thought, / And rolls through all things” (301)/ Wordsworth even declares that nature guides his life and moral compass: “[t]he anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse, / The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul / Of all my moral being” (301). Nature suppresses the power of God to reign in the hearts and minds of men by surrounding them with its power, drawing them into worshipping the created instead of the Creator. I find Wordsworth’s descriptions of nature and the pull it has on him to be particularly interesting as Wordsworth seems to be “a worshipper of Nature” himself.

Also, I looked up pictures of Tintern Abbey and it is really nice, I can now understand Wordsworth’s fascination with it; so here are some pictures.