Jesse Gross ’22

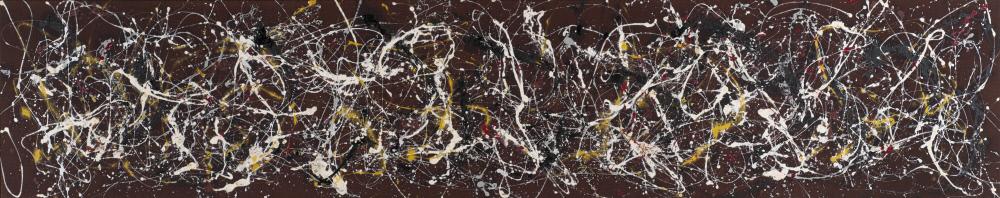

Sprawling blotches of white, black, yellow, brown, and red seemingly haphazardly envelop the dark burgundy fabric that composes the canvas. Pollock’s work stretches 15.8 feet wide and 3.6 feet tall. Its frame is small and unimportant, a simple means of showcasing the work itself. While at first the paint seems simply strewn about the canvas, intricacies begin to rear their head as the viewer zeroes in on a single section of the painting. From afar, one can view the spectacular show put on by Pollock, each toss of paint like a path of a dancer, following elegant, practiced, and complex movements that only a professional can express. But as the viewer moves closer, and by nature of the size of the work, into a more specific section of the canvas, intentional marks emerge. They do not define any shapes and do not seem to hold any tangible meaning, but they begin to blend as the two strokes cross, mixing the colors into new unknowns. While from a distance the shapes only seemed to cross over each other, only glimpses of moments of interaction, up close their compositional nature comes forward.

The work is titled Number 2, 1949, and was completed by Pollock in 1949. In classic Pollock fashion, he used oil, Duco, and aluminum paint. It is an example of the use of his pouring technique. The use of cloth rather than a traditional canvas allows for a new found expression of the paint, the bleeding of yellow from its center outwards creates a ghost like effect, scribbled sections mix and blend but do not create new colors. Instead they simply exist and play together, coming through individually in areas that would have been conjoined on a more traditional medium. These aspects of the painting lend themselves quite nicely towards Pollock’s eccentric take that paint itself has a life of its own, and his technique only stands to amplify that hypothesis. The circular and free flowing yet vaguely articulated shapes are rich with paint all across the canvas, a feat achievable by manipulating the canvas in a non-upright position. Splattered splotches allow the paint to fall wherever it so chooses without the restrain of intention of its thrower. And yet, there does seem to be some intention.

A heavy drinker and described as “a shut-in and inarticulate personality of good intelligence, but with a great deal of emotional instability who finds it difficult to form or maintain any kind of relationship” by his personal psychiatrist, Dr. de Laszlo, Pollock is showcasing just how loud and intrusive his thoughts are. Unpainted space finds its way through the marks, but only in small instances, encroached upon by splatters and splotches, never allowing the viewer a moment for reprieve. This seems to be the mind of Jackson Pollock, a painter who was touted as the best in America many times over by his critics. Yet he remained a difficult personality until his untimely death. Characterized with “a certain schizoid disposition” again by Dr. de Laszlo, this, and much of Pollock’s other work, allows for a glimpse into his hectic mind. Yet the work feels like a channeled version of that illness, rather than letting it run rampant, Pollock finds direction with his strokes, forcing his thoughts in beautiful and articulate yet incoherent ways, forming a fascinating piece of work that few have been able to rival in American Modernism.

References

- MWPAI Online Collections