A Fine Disregard

An exhibition by Hillary Bisono Ortega ’21 and Mary Bei Prince ’20

The exhibition screenshots below contain embedded information and/or media panels. Click the icon, ![]() , to view this material.

, to view this material.

In naming his book A Fine Disregard: What Makes Modern Art Modern, Kirk Varnedoe commemorates the creative conception of Rugby, in which William Webb Ellis demonstrated “a fine disregard for the rules of football,” to emphasize the new ways in which Modern artists created work and saw the world. Modern art coincides with a fervor of experimentation that is associated with a break from tradition. As such, artists threw aside conventional techniques and subject matter, disregarding a legacy of art that emerged during the Renaissance. Instead, they sought inspiration from the east, consuming Japanese Woodblock Prints and morphing tribal depictions into primitivism. The simpler shapes and abstracted figures, found in art that was more readily available and affordable, diverged from traditional European and American styles of representation that focused on realism. Likewise, non-western art offered a deeper and more complex emotional and spiritual model that the artists employed (in a critique of the modernization of Western Society). Despite the playful moniker that Varnedoe uses to characterize the Modern art movement, a Fine Disregard also illustrates the disregard for the cultural legacies that western artists appropriated.

Traditional conceptions of the American modernist movement lack any consideration or representation of artists who are non-white, womxn, or queer. Instead, scholarship focuses on a more Eurocentric telling: championing artists who take from eastern style and ideology while encouraging long-enduring assumptions that these cultures were inferior. Why is it that when we are asked to consider “fine art,” we fail to include the voices of others? This exhibition is A Fine Disregard of the ‘Fine Disregard’.

The Path

The Inside

American Modernism revolutionized the depiction of daily life, giving new meaning to still lives through simplified compositions and gestural strokes. Flowers by a Chair (1935) and Grapes, Peach and Pear (1935) both illustrate the interior quality of everyday life.

As an early work, Quita Broadhead’s painting illustrates the influence of European modernists like Cézanne through its vibrant colors and the applique of pigment. She reimagines the flowers, using patches of color to delineate as well as abstract forms. While Broadhead gained limited success during her lifetime, her respective contemporary obscurity demonstrates the complexities associated with reconsidering the canon of Western art and its exclusion of women artists as she refrained from identifying as a feminist. Re-examining female artists like Broadhead within the feminist art movement may overemphasize this categorization, which perpetuates their separation from a traditional canon while relegating them to a specific niche. Thus, Broadhead demonstrates a fine disregard through her painting as well as her legacy.

Fusing three traditions–early American folk art, European modernism, and Japanese painting–Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s style evolved throughout his career: shifting toward naturalism in the 1930s and then abstraction in the late 1940s. Grapes, Peach and Pear demonstrate a more stylized image. From the broad cross-hatched regions of the grapes to the sharp fluctuations between light and shadow on the cloth, every stroke is visible. Yet the composition juxtaposes this sense of stability as the cloth seems to conceal a mass of objects. This contradiction may relate to Kuniyoshi’s internal struggle with his Japanese identity. Although he promoted a modernist trope of universalism to define American art, Kuniyoshi understood the extent to which his race and nationality factored into the American public’s perception of him.

The Outside

Defined as a place or a region beyond an enclosure or boundary, the ‘Outside’ contains the works of Henry Ossawa Tanner, Ilse Bing, and Reuben Tam. Moonrise, Tangier (1912), Migration Images (1944), Waipahee Mountains (1949), and Windows and Vines (1934) all depict the outside world. Understanding the personal histories of the artists allows us to comprehend their retrospective and contemplative approach, as all of the artists engaged in travel to places that were considered “alien” to the inside world. Tanner, having spent some time in Europe, settled in the Middle East, escaping the unfriendliness the American art community had towards him. Producing works exhibiting various mosques and biblical sites, his paintings developed a powerful air of mystery and spirituality, one being Moonrise, Tangier based on his travels to Morocco. On the other hand, Ilse Bing, a Jewish woman living in Germany, escaped persecution by immigrating to America. Bing’s work in Germany was highly acclaimed, renowned for its soft and ethereal feeling, whereas her work in America represented her plight distinguished by its sharp edges and stark contrast.

Combined, the stories of Tam, Bing, and Tanner represent the need to understand that which lies beyond us. They demonstrate the dichotomous relationship between interior and exterior, using scenes of the outside world to represent a transition between domains. Likewise, they interrogate the ways in which foreign perspectives frame our experience within the US.

Inside Looking Out

Ilse Bing’s Michelle at Window and Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s By the Sea both illustrate a certain ambivalence. The photograph illustrates a child peering into a window. Drawing the curtain back slightly with her left hand, she also clutches her doll’s dress with the same yearning for security. The soft gradations of color within the ruffles juxtapose ordered textures present in Michelle’s own garment, demonstrating a tension between freedom and order. Bing illustrates a sense of longing that reflects the circumstances in which she fled her home country.

Kuniyoshi’s painting demonstrates the same sense of longing. The painting features a woman resting her head against her hand, looking into the distance. While this posture illustrates a sense of yearning, the gestural quality of the paint strokes also demonstrates an agitation: from the contouring of her body to the wisps of her bangs and the background. The period of political awareness spurred by the events of World War II influenced Kuniyoshi’s work. As a Japanese American, he struggled to maintain his identity as an American citizen, contributing to the war effort by recording radio propaganda. The tone of By the Sea reflects this melancholy derived from the state of world affairs.

Inside Looking Out demonstrates the ways in which artists reflect their complex identities: how cultural and ethnic differences are manifested politically and their social consequences.

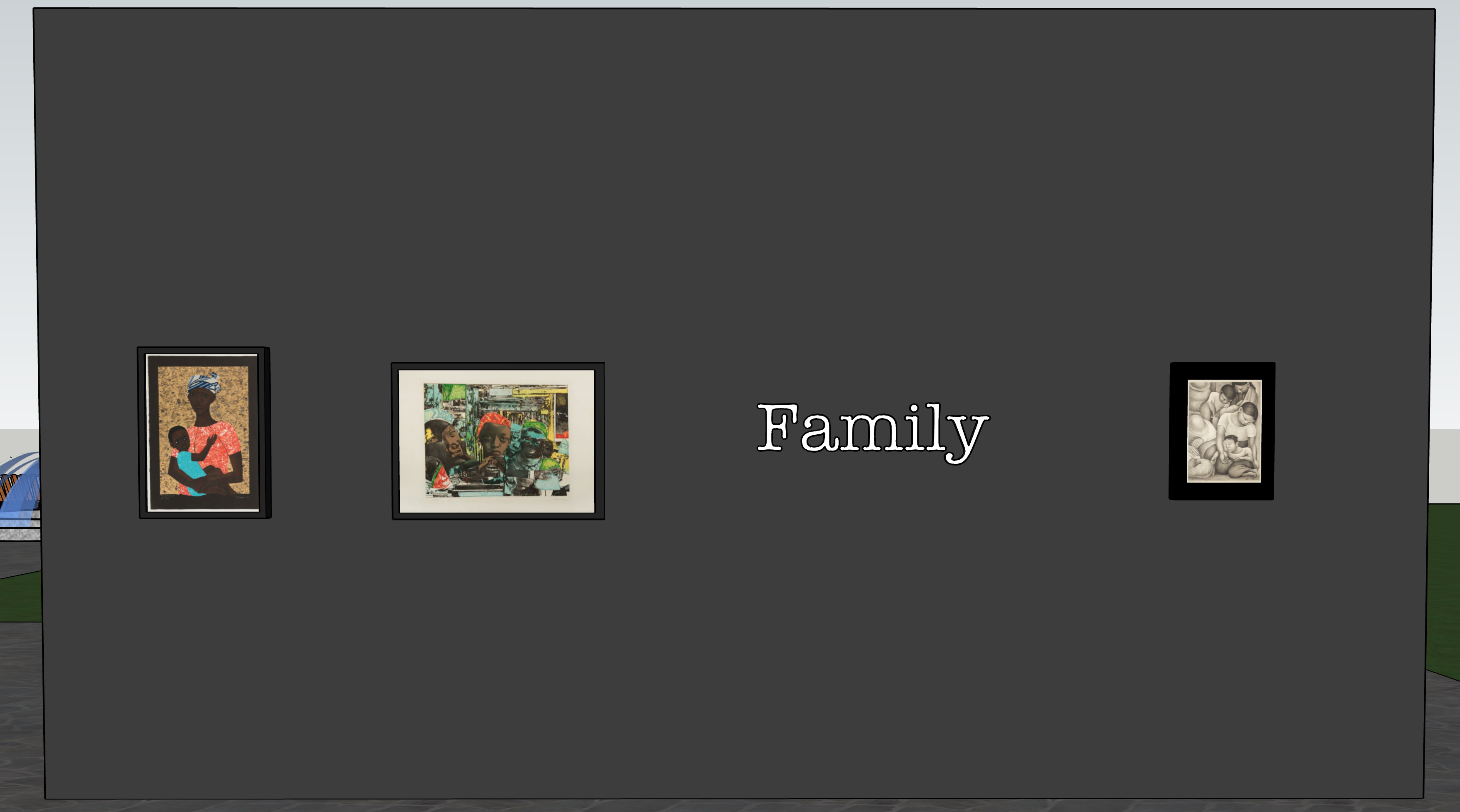

Family

As the grandchild of freed slaves, Elizabeth Catlett was an African American graphic artist and sculptor well-known for depicting the African American experience through a female perspective. Growing up, Catlett’s parents reinforced their ancestry and the importance of familial bonds. Madonna II (1992) depicts an African American mother holding her child tightly while gazing towards the viewer. Madonna II references traditional images of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child as well as African mother-and-child compositions even as it delves into the relationship between two and three dimensions, presenting its human forms as articulated by somewhat abstracted planes.

Romare Bearden’s collage The Train (1975) references many cultural sources, from African sculpture, Cubism, Dada photomontages, and American Pop art. His photostat process enlarges images from art-historical text and popular magazines to emphasize their graininess and imperfections. Bearden believed that trains “could take you away and could also bring you to where you were. And in the little towns, it’s the black people who live near the trains” (SOURCE: Alcauskas, INNOVATIVE APPROACHES, HONORED TRADITIONS, 2017). The depiction of the train also occupies the left background, a relegation of space. Likewise, the prince alludes to a part of Bearden’s childhood, depicting an African American family seated at a table inside a house. Moreover, the piece also reflects widespread stereotypes and his misgivings about them. Collectively, The Train symbolizes migration and the persistent forces of segregation while also emphasizing the family as a centering force.

As a leading figure in Social Realism, Diego Rivera demonstrates Mexican history and political strife, his identity, and a celebration of the working class in his art. Rivera was a muralist who utilized a centuries-old fresco technique to create large-scale, politically engaged public artwork. He began experimenting with lithography to make money and disseminate his art, and although he replicated imagery used in his murals the different medium allowed him to capture more intimate scenes, like that in Sleep, in increased detail. Sleep then represents the exhaustion of the working class by illustrating the physical fatigue from merely existing at a disadvantaged position. Like Catlett and Bearden, Rivera underlines the family as a unifying presence in the midst of adversity.

Interactive 3D Model

Click the image above to activate the 3D model viewer. The 3D model viewer may take a minute or two to load.

Within the viewer you will be able to orbit, pan, and zoom the 3D model. Select the arrow located on the right side of the 3D model viewer to access these tools.