Stuart Davis and American Abstraction

Stuart Davis entered the art world with the tenacity and skill to become a modern artist whose creative method would be characterized across his colorful, orderly compositions. Davis was “educated out of the Ashcan School of realism” (Lane 5) and at the young age of 21, attendees of The Armory Show saw five of his watercolors painted in the Ashcan style on display at the event in 1913. In reflecting on the Armory Show, Davis wrote years later that he was “enormously excited by the show, and responded particularly to Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Matisse, because broad stylization of form and the non-imitative use of color were already practices within my experience” (Davis). The painter, however, “sensed an objective order in these works which I felt I was lacking in my own” (Davis) prompting him to feel dissatisfied with the training he received at the Ashcan school.

Because the Armory Show marked the first time that Davis saw examples of Cubist and Fauvist paintings, he came to realize that there were no American paintings of this sort. He “resolved that I would quite definitely have to become a ‘modern’ artist” (Davis) to fill the gaps that his predecessors, the American painters, had left behind. He would embark on a journey of self-directed exploration that steered away from directing so much attention towards the subject and rather focused on the formation of his own inimitable method of painting that would “be distinctly American” (Davis).

As Davis developed his individual style, the foundational approach to Cubist compositions– with an emphasis on the flat two-dimensional surface of the canvas and fragmentation of geometric forms– would inform his artistic practices. Additionally, he maintained the idea that there was room to refine and personalize this style of painting. Because the “broad stylization of form” and “non-imitative use of color” that he saw in paintings at the Armory Show were methods that already fell within his practices, Davis set off to take what he knew, what he saw, and what he hoped for to capture the dynamic American scene in his paintings.

My interpretation of Davis as a painter is that he was a conceptual thinker who took his everyday experiences and synergized them by distilling identifiable fixtures and landscapes of American life to their essential forms. He drew from his surroundings, interests, and elements of popular culture to paint subjects that broke from their real world presentation, to offer his own fascination-infused interpretations of them in his art. Thus, Davis’ paintings presented the American experience through refined motifs that captured contemporary content.

In the years to follow the Armory Show, Davis brought a new style to fixtures of American society by painting from life. He strayed away from traditional subject matter and instead drew from modern American subjects. This shift in subject led him to create the “Eggbeater” series, a bold set of Cubist-inspired still life paintings of what the majority considered to be ordinary objects, but Davis treated as important subjects to study in great detail. The series consisted of four oil paintings, Eggbeaters Nos. 1-4, one of which, Davis’ Egg Beater No. 2 of 1928 was bought by Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. In his autobiography, Davis wrote that “the culmination of these efforts occurred in 1927-1928, when I nailed an electric fan, a rubber glove and an eggbeater to a table and used it as my exclusive subject matter for a year” (Davis). In doing so, Davis was able to focus on the elements of the object so closely that he was able to eliminate any recognizable traits of the item so that the viewer could interpret the shape, form, and function of it for themselves.

Egg Beater No. 2 is a conventionally focused but abstractly executed painting. Davis formed a space in which the free-flowing shapes that constitute the eggbeater coincide with each other in an orderly fashion. There are no defining characteristics of the eggbeater in the painting, which expresses the contemporary qualities of the subject itself. The abstracted geometric forms are placed inside of a room providing viewers with a space to explore the relationship between the eggbeater and its placement both visually and mentally. Egg Beater No. 2 speaks to a concept that Davis created called ‘Color-Space’, which he defined as “the observation and thought that every time you use a color you create a space relationship” (Arnason 44). The interplays of surface and depth are complemented by the saturated darker hues of the egg beaters’ parts and pastel colored surrounding walls. The egg beater is thus arranged on the canvas to create a similar viewing experience that one would have if they were looking at the subject in a stationary state, while also carrying a certain energy through the shapes being overlapped to show that it could fill the space in which it was placed if it were in motion.

The logical elements of Egg Beater No. 2 displayed various aspects of the object simultaneously rather than the methods of an analytic design. The curved lines of the eggbeater suggest its movement as a hand-operated machine of the mechanized 1920s kitchen and the electricity it requires to work and serve its purpose for American families. He developed a sense of unity in the composition as the form of the eggbeater becomes the sum of its parts, eliminating the traditional notion that objects need to be presented in a specific way in order for viewers to understand what they were looking at. In his autobiography, Davis noted that this approach was not to be regarded as “the future aspect of all my painting, but rather as a structural concept” (Arnason 42). Davis experimented with the geometric elements of objects and the recessions of planes to strip the subject of any complexities, making for a simplified composition that brought new life to a fixture of American culture.

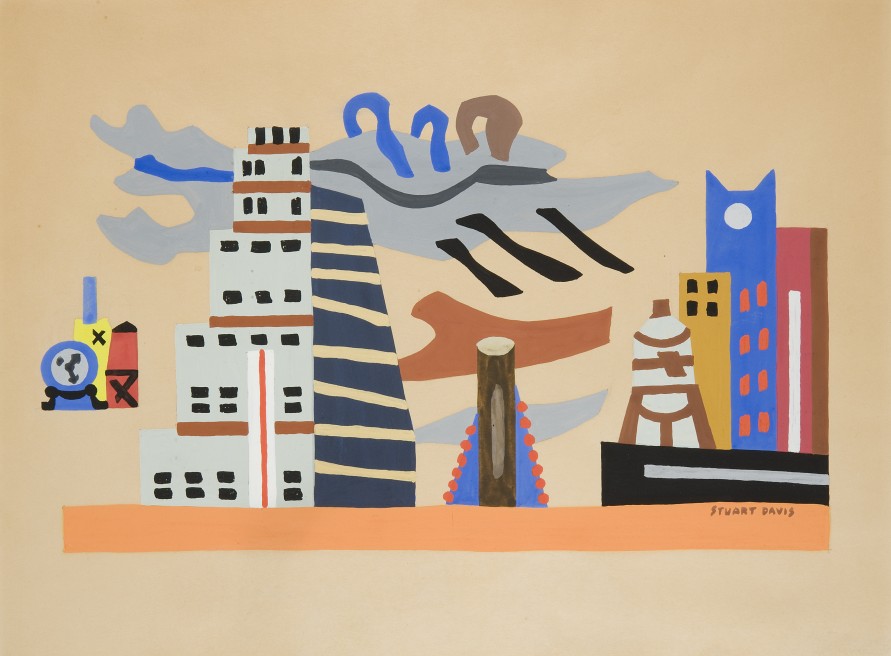

Because Davis wanted to capture the fundamental experience of American life in his art, he also took to painting the outside world and carried this unconventional structural concept and use of geometric forms with him when creating landscapes. Davis’ Skyline from 1938, owned by Karen and Kevin Kennedy, is a painting in which the spatial illusion of geometric forms making up the New York City skyline articulates the setting of the work. To translate the three-dimensional nature of the buildings, Davis constructs a pictorial vision of the city across a contrasting color palette and layout of the skyline.

As he drew from the metropolitan landscape and his respective surroundings, Davis brings symbols of urban life like a water tower, highrise buildings, and smoke into Skyline. The difference in the types of architecture in the painting marks the continual urban transformation of the skyline. The larger buildings in the forefront of the composition appear to be more modern in design than those placed on the right and further from the groundline that Davis establishes towards the bottom of the canvas. Behind the buildings on the left side of the composition, there is a clock and front in center, there is a tree stump that marks the passage of time and society was moving towards industrialization, production, and building upwards.The modern buildings in the front appear to be much more bleak and carry less character than those on the right, and by implementing his ‘color-space’ concept, Davis creates a depth of field for the viewer as they look upon the city skyline to see how it’s changing, moving from left to right, towards the new and away from the old.

Skyline is reflective of the dynamics of American life in New York City during the twentieth-century through its colorful, bustling nature. He embraces the modern energy of the city and the rise of industrialization with smoke in the sky. Because Davis was concerned with the ever changing nature of his surroundings, his depiction of New York City in Skyline was the product of his experiences with the American environment. He also uses red, white, and blue in this painting, emblematic of his patriotism to the country. The tempo of the fast-paced American experience in New York embedded in Skyline, contributes to the vitality of his work.

In a similar fashion to Egg Beater No.2, Davis’ Skyline has the ability to channel energy and motion while existing as a two-dimensional medium dispensed with three-dimensional form through the use of line, color, and patterns. Davis gives meaning to details by forming compositions that included only the most essential parts of his subject. Whether it was an American object or experience, Davis felt that “in one way or another the quality of these things plays a role in determining the character of my paintings. Not in the sense of describing them in graphic images, but by predetermining an analogous dynamics in the design, which becomes a new part of the American enviorment” (Davis 35). I chose these paintings because they are showcase different embodiments of Davis’ dedication to paint what he saw in America. “The way that over four decades he kept reimagining, and making more imposing, his art of form and color” (Schwartz) shaped his aesthetic mission to merge American life and design of abstract concepts in his work.

Davis’ paintings are telling of his individual application of principles and concepts to his art. His still lifes, landscapes, and figurations distinguished his systematically and consciously driven career to become the “‘modern’ artist” for America that he longed to be. The continuity in his commitment to depicting the American experience is emblematic of how his innovative concepts and unique style distinguished him as his own type of painter– one who infused elements of design and form with a depiction of real life. Davis enthusiastically embraced the symbols, staples, and pace of America’s burgeoning commercial culture in his art: a painter who carved his own path of American Abstraction.

Works Cited:

Davis, Stuart. “The Cube Root.” Art News, February 1, 1943.

Davis, Stuart. Stuart Davis. New York NY: American Artists Group, 1945.

Arnason, H.H. Stuart Davis, 1894-1964. London: United States Information Service, 1966.

Lane, John. Stuart Davis: Art and Art Theory. New York, 1978.

Schwartz, Sanford. “He Made It American.” The New York Review of Books. Accessed September 22, 2019. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2016/10/13/stuart-davis-full-swing-made-it-american/