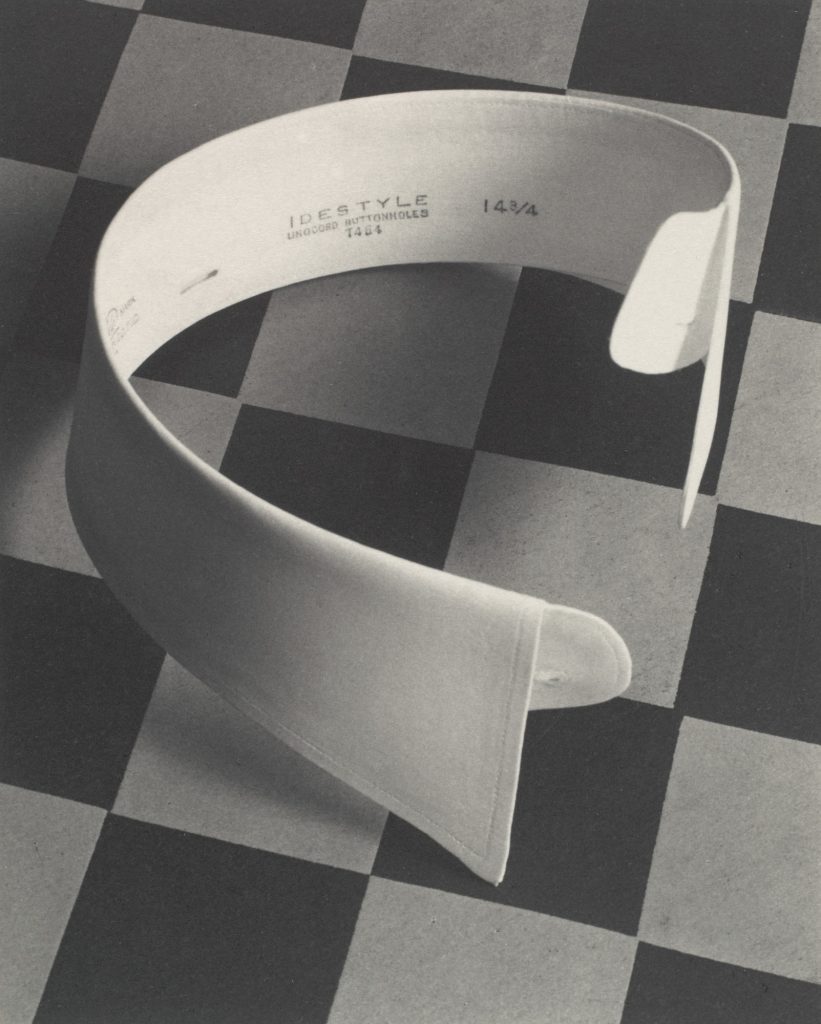

Paul Outerbridge, Jr., Ide Collar (An Advertisement made for Geo. P. Ide & Co.), 1922.

“No one today, we can hope, believes that photography is so mechanical a business that a photograph cannot be a work of art”. However, in 1839 when photography was first publicly announced, it was viewed as a technical/scientific invention that would be useful for documenting the realities of the world around us rather than as an art form. The 20th century/modernist era is marked by the re-imagining and rejection of ‘traditional’ art. One resulting conflict was diverging views on the medium of photography as a fine art and the value of varying techniques that arose. At the same time there was a divide surrounding the ideologies about what American art should look like at the turn of the 20th century, particularly between realism and the growth of abstractionism seen through the growth in surrealism in the early 1900’s . Paul Outerbridge, Jr., an American photographer known for his fashion and commercial photography, experimentation with the tri-color carbro process, and, later, his then-controversial female nudes, entered the art scene in the 1920’s, contextualized by the conflicts listed above.

Paul Outerbridge questioned the shifts and conflicts between photography and painting that emerged in the early 1900’s. Photography was influenced by the changes in paintings during the time and vice versa. “The Eight,” formed in 1908, was a group of American painters whose formation exemplified the varying views and re-imaginings of art demonstrated through the change in the aesthetic and techniques painters used and valued as fine art. “The Eight” sought independence and power as artists through the rejection of traditional, aesthetic, institutions and academia, and desired to depict real/everyday life. The group believed that the start of the 20th century was tarnished by “‘a deceitful age, drugged in the monotony of pretty falsification’; American art had become ‘merely an adjunct of plush and cut glass”. They rejected the formal, polished, and ideal subject matter of Impressionism and the repetition of romanticism that previously defined European art, promoting the movement of realism.

On the other hand, other groups of artists also began moving toward abstraction through the development of surrealism in the 1920’s. The rise and changes in photography demonstrate one path in which surrealism grew, contrarily to realism. Artists began to reject the “objectivity” associated with photography’s first use to create images of real life. This shift initiated the pictorialist movement in which artists focused on the craftsmanship of photography, rather than its technical function to quickly capture a snap-shot of a moment in real life. Straying from realism, pictorialists used techniques such altering the focus, moving the camera, altering the duration of development, the addition and use of different materials, and were influenced by movements, created by painters, like cubism. Pictorialists manipulated their images in order to associate with and mimic the reworking capabilities of painters. Artists’ manipulation of their images was done with two hopes in mind: that it would demonstrate the expressive and meaningful effects that photography was previously thought to lack; and elevating the aesthetic beauty of photographs so that the medium of photography would be valued as fine art.

Outerbridge recognized the alteration of artists’ ideologies and techniques and their impact on the acclaim and aesthetic value of photographs during the period in which he established himself as an artist. Unlike artists who conformed to these changes, Outerbridge maintained his unique vision, “unwilling to compromise with changes in fashion or taste”, rejecting, contradicting, and incorporating elements he believed were in line with his imagined perfect style/aesthetic. Outerbridge’s evolution as a photographer, despite his work’s varying techniques, subject matter, and purposes, is made cohesive through his focus on form; his belief in the singularity of photography as a means of expression; and his devotion to the medium of photography, whether commercial or not, as fine art. The cohesion of Outerbridge’s central visions are exemplified in an exhibition consisting of all the known images produced by Outerbridge between, 1921-1941 amounting to over 540 works, organized and exhibited first by, the Laguna Beach Museum of Art in 1981. The exhibition was titled, Paul Outerbridge, A Singular Aesthetic; commenting on the strength of Outerbridge’s unique vision throughout his career.

Outerbridge was born in New York in 1896, situating him at the center of several modern art movements and in proximity to several of the most highly regarded modern artists. He began his art education at the Art Students’ League in New York in 1915-1917, where he explored illustration and worked for a theatrical stage designer beginning to form his stylized vision, and continued his education in 1921, studying with American photographer and member of the Photo-Secession movement Clarence H. White and Max Weber, one of the first American Cubist painters, at the Clarence H. White School of Photography. Both White and Weber’s influence on Outerbridge’s career is evident in his use of cubism and promotion of photography as a fine art. Instead of graduating, Outerbridge was asked to teach there, showing his natural talent in photography, particularly as he had only taken his first photo in 1917 after enlisting in the United States Army at the start of WW1., He was given the job of documentation at an airplane construction facility and was given a camera to do so, igniting his career, which was legitimized in 1922 when his first photograph was published in Vogue.

Early in his career one of the defining features of Outerbridge’s photography contradicted the emerging realist ideology that the value of American Art had fallen to materialism, caused by the increase in industries and economic growth in the US after the Allied Powers’ victory in WW1. The growth in consumerism lead to an increase in advertising, in which Outerbridge’s philosophy that “Art is life seen through man’s craving for perfection and beauty— his escape from the sordid realities of life into a world of his imagination” when applied to his production of photographs, allowed him to excel in and re-imagine the advertising industry. In the span of four years he started the largest advertising studio in Paris and become the highest paid image creator in New York in 1929. Outerbridge’s career as a commercial photographer, both in black and white and color, came to an end in 1943. His work was overlooked at the time it was created. It was overshadowed by his controversial, often taboo, images of nude women and a resulting scandal. Despite Outerbridge also refusing to conform to the shifting popular aesthetics at the time; the formal, intentional and styled aesthetic of Ide Collar demonstrates Outerbridge’s ability to merge commercialism and art and the broader power of photography to transcend and even utilize materialism to produce images that both function commercially and are regarded as fine art.

One of Outerbridge’s most famous images that depicts the cohesion between the commercial and artistic sides of Outerbridge’s photography, is his image, Ide Collar, 1922; it is a vintage gelatin silver print that is part of the Keven and Karen Kennedy Collection, in New York City. Ide Collar was created and ran in the 1922 issue of Vanity Fair for the George P. Ide company, marking the first of many fashion advertisements for Outerbridge. The image is composed of a white removable Ide company shirt collar; the subject is positioned on top of a black and white pattern resembling a checkerboard. The collar is curved, giving it a rhythmic shape, hinting at its malleability and perhaps its functionality. Despite the collar’s organic shape, Outerbirdge’s use of sharp focus on the edges of the collar gives it a defined and formal appearance. Outerbridge’s use of lighting casts a shadow on the collar leaf in the center left of the image. Along with its position next to a black square, it creates the darkest point visible on the collar. The contrasting shades created by the light’s shadow creates a distinguished separation between the collar and the checkerboard, making the collar appear as if it is 3D within a 2D photograph, creating depth defined by the collar’s height. The lack of a frame around the image, although it is uncertain if the photo was meant to be viewed with/without one in Vanity Fair, creates the illusion of depth on the edges of the image; the diagonal slicing of the checkerboard makes it appear as though they are folded downward, creating the illusion that the photo itself is 3D like a box. The centerline on the checkerboard divides the image diagonally, though as it is crosses from the foreground to the background it is intercepted by the collar, which appears slightly elevated off the surface, creating a small source of light created by the collar’s curved shape that draws attention to Ide Style’s branding which is further emphasized by the light. The lighting, along with the angle of the camera, makes the company’s branding the central focus of the image, despite its location further in the background.

The composition of Ide Collar reflects Outerbridge’s reaction to the shift towards pictorial photography. Outerbridge agreed with the sentiments of fellow American photographer Paul Strand who, in response to pictorialism, sought to re-establish the value and traditions of “straight” photography. Strand argued that “it is in the organization of this objectivity that the photographer’s point of view toward life enters in”. Like Strand, Outerbridge agreed with pictorialists’ idea that it is through manipulation that photographers define their intentions and impose abstraction on to the work. As demonstrated by Ide Collar, however, Outerbridge rejected pictorialism and instead practised ‘’straight” photography. The physical photograph itself is not distorted. Outerbridge rejected the notion that the photograph itself must be distorted in order to be valued as surreal or abstract, because of pictorialists’ idea of images depicting reality without distortion were objective. Instead, as is visible in Ide Collar, Outerbridge distorted the reality depicted in his photographs, distorting elements such as scale, incorporating artificial lighting, positioning objects, etc. in ways that we would not normally view them, like the size of the collar in comparison to the checkers or its 3D appearance.

Ide Collar, 1922 provides evidence of the ways in which Outerbridge utilized and accepted surrealist and realist ideologies of fellow artists at the time, while also rejecting or fully contradicting others. Outerbridge’s photography, like the ideals of realism, stray from traditional art. They are similarly influenced by everyday life and commonplace objects; Outerbridge, like the realists, focused on the ordinary or often undervalued subjects rather than those that were idealized in movements such as impressionism. On the contrary, in response to realists’ desire to reject traditional romanticized aesthetics and formal teachings Outerbridge argued in his own words “’there can be no art without composition or design, and careful study of the old as well as the new masters, will reveal an underlying abstract composition in all their work”. Outerbridge rejected this idea and was often influenced by the formal and polished aesthetics of ‘old-masters’ artwork, particularly when creating photographs for professional use. Similarly, Outerbridge’s capability “to elevate [the] advertisement for Ide shirt collars from a simple sales solicitation to a stylized still life”is hard to imagine and must have required “fierce attention to tone, lighting, and composition”. Outerbridge’s work directly contradicts the philosophy of suppressing conscious control behind surrealist automatism as Ide Collar and other similar images rely on conscious, calculated decisions. Ide Collar, like the shift in photography from real life snap-shots toward the abstraction through manipulation, represents Outerbridge’s transition toward the surreal based on his devotion to the precision of form in his first ad.

The image is composed of two simple objects, a collar and checkerboard, but Outerbridge’s belief that “Even in the back of the apparently most concrete subjects the underlying abstract will be found” shifts interpretation of the image from the simplicity of an object being advertised for consumerism to understanding it based on Outerbridge’s incorporation of the surrealists’ practice of deriving abstraction from forms and symbols. This understanding of surrealist influence on Outerbridge’s work opens the door for deeper abstraction of the forms in Ide Collar. First based on the “underlying ideal of formal beauty” to inform the abstraction of objects that is carried throughout Outerbridge’s artwork; and secondly his seperation of the expression of photography as a fine art from other media. It makes me think that in his first image produced for commercial use, he would want to reflect his two key visions. The formal qualities of the checkerboard and the collar are distinct and almost opposite from one another, creating a contradiction between the two.; however, I think that this juxtaposition in the objects’ formal qualities, such as the geometric repetition of the checkerboard in contrast with the curved form of the collar, benefits both objects equally. Without the contrast of the checkerboard’s form, the collar’s curve and light shading would not have the same effect. Likewise, the geometric and linear form of the checkerboard as well as its darker coloring and shading would not stand out without the contrast of the collar and would be interpreted as a gameboard. The contrast of the collar’s sharp curve formalizes the artistic value of the checkers, while the checkers increase the aesthetic value of the collar. This demonstrates not only Outerbridge’s ability to straddle both fashion and art, but also how the formal qualities of objects in images can be used to benefit each other and the image’s beauty as a whole, formalizing photography as a fine art.

Bibliography

“Advertisement for George P. Ide & Company.” The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Accessed September 27, 2019. https://www.mfah.org/art/detail/3663.

Barnet, Sylvan. “Asking Questions to Get Answers .” In A Short Guide to Writing about Art, Third ed., 21–49 . United Kingdom : Hopper Collins , 1989.

Darlington, Andra. “Finding Aid for the Paul Outerbridge Papers, 1915-1979 (Bulk 1922-1958).” Online Archive of California. Accessed September 27, 2019. https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt087031vj/entire_text/.

Dines, Elaine, Graham Howe, and Bernard Barryte. Paul Outerbridge, a Singular Aesthetic: Photographs & Drawings, 1921-1941: a Catalogue raisonné. Laguna Beach: Laguna Beach Museum of Art, 1981.

Hostetler, Lisa. “Pictorialism in America .” metmuseum.org. Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed September 27, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pict/hd_pict.htm.

Milroy, Elizabeth, and Gwendolyn Owens. Painters of a New Century: the Eight & American Art. Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee Art Museum, 1991.

“PAUL OUTERBRIDGE JR. (1896–1958) , Ide Collar, 1922.” Christies . Accessed September 27, 2019. https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/Lot/paul-outerbridge-jr-18961958-ide-collar-1922-6098147-details.aspx.

Smyth, Diane. “The Lasting Allure of Paul Outerbridge.” British Journal of Photography, August 3, 2017. https://www.bjp-online.com/2017/08/the-lasting-allure-of-paul-outerbridge/.

Tate. “Automatism – Art Term.” Tate. Accessed September 27, 2019. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/automatism.