Charles Burchfield’s Blackbirds, Spring Rain, and Crows in March

Charles Ephraim Burchfield (1893-1967), an American artist born in Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio, famously painted watercolor landscapes. After graduating from the Cleveland School of Art in 1916, Burchfield lived in Buffalo, New York. Drawing inspiration from the “streets, harbor, railroad yards, and surrounding countryside” of Buffalo, Burchfield developed his taste for realism, and consequently, painted in this style for years. The Frank L. M. Rehn Galleries in New York represented Burchfield in 1929, which marked the beginning of his growing popularity as a professional artist. His work has been displayed in art institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Carnegie Institute, and the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art, and was featured as one of the ten greatest American painters in a 1936 issue of Life magazine.

Edward Hopper—one of his friends and a fellow artist—described Burchfield’s work as, “most decidedly founded, not on art, but on life, and the life that he knows and loves best,” primarily depicting landscapes. He captured in in watercolor paintings subtle moments of nature, such as “snow turning to slush, the sounds of insects and bells and vibrating telephone lines, deep ravines, sudden atmospheric changes, [and] the experience of entering a forest at dusk.” While his work is representational, his style reflects his leaning towards emotion rather than realism. He described his own work as portraying “the romantic side” of the world, and wrote, “My things are poems—I hope.” Burchfield’s consistent use of watercolors for his paintings “imbued these subjects with highly expressionistic light, creating at times a clear-eyed depiction of the world and, at other times, a unique mystical and visionary experience of nature.” His artwork reflected not only his own growth and maturity as an artist, but the context of when he was a practicing artist. During World War II, Burchfield’s participation in the army produced works such as his untitled watercolor of a camouflage design in 1918, which he described as it being “impossible for me to do straight camouflage. I had to have a poetic idea back of my designs.” Even when the subject matter and psychological significance shifted in Burchfield’s work, he still retained his poeticism and dream-like style throughout his whole career. This is exemplified in the works, “Spring Rain,” “Blackbirds,” and “Crows in March,” two of which were made in the earlier part of his career, 1916, while the latter was made in 1951.

The Ruth and Elmer Museum of Art in Clinton, New York, contains three of Burchfield’s work in their permanent collection: two watercolors, “Spring Rain” and “Blackbirds,” and one lithograph, titled “Crows in March.” While “Spring Rain” and “Blackbirds” were bequeathed by Daniel W. Dietrich II, class of 1964, “Crows in March” was a museum purchase with the Gilman L. Sessions Memorial Fund. In 1970, the watercolors were exhibited together in the exhibition, “Interpretations of Nature: an Exhibition and Sale of Early Watercolors by Charles Burchfield” at the Bernard Danenberg Galleries in New York, NY. Almost fifty years later in 2017, these two works were displayed together again in “Innovative Approaches, Honored Traditions: The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Five Years, Highlights from the Permanent Collection.” These three works of art serve as prime examples of Charles Burchfield’s style and subject matter in the early and later part of his career.

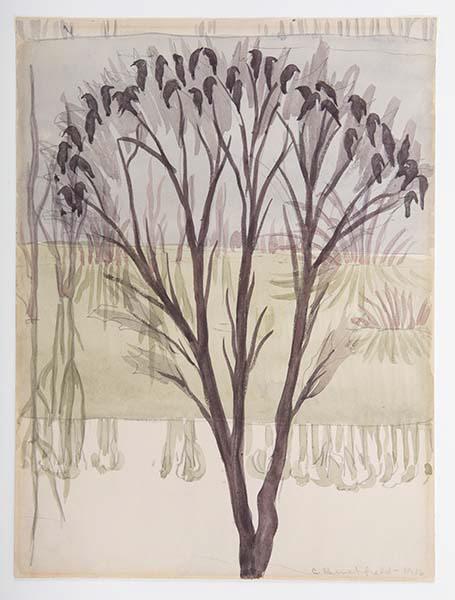

“Blackbirds,” (11 15/16” x 8 15/16”) completed in the first half of Burchfield’s career in March of 1916, is a watercolor and pencil on paper. Reminiscent of Japanese ukiyo-e color woodblock prints because of Burchfield’s study at the Cleveland School, “Blackbirds” uses different values of purple and green to represent reflections, shadows, and forms. The subject is a grayish, brown tree with blackbirds perched at the top of the branches, forming an arch. The blackbirds, though discernible as perching birds in various positions, look almost like abstract shapes when viewed up close. The background is broken up into three parts: purple, green, and beige. Using darker shades of purple, loose forms of grass take over the upper half of the composition. Burchfield uses a darker shade of green to portray reflections of the grass, as the forms mirror the purple ones. He signed the lower left hand corner in pencil, “C Burchfield – 1916.” Burchfield’s work is effective in its simplicity of line and color and reflects his blend of representational forms and whimsy, abstract forms. Additionally, this watercolor demonstrates a playfulness that seems to be prevalent in his work; some of the forms have no reflection, and vice versa. Rather than focusing on the truthful portrayal of his subject matter, Burchfield instead uses elements of realism and imagination to reach viewers in an emotional sense. This is also demonstrated in “Spring Rain.”

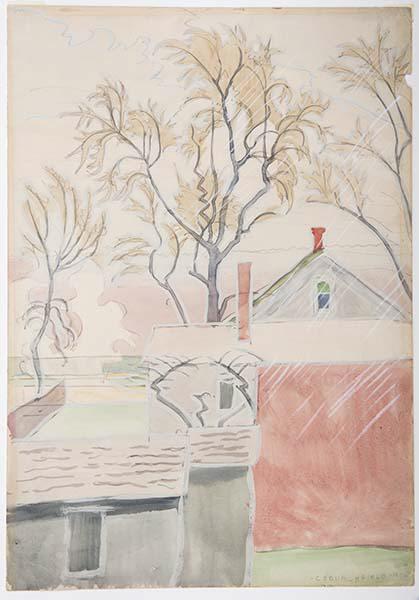

The other watercolor in the Wellin’s collection, “Spring Rain” (20” x 14”) was completed only a month later, on April 1, 1916. As one of Burchfield’s other work, “Backyard,” depicts the same scene but from a different point of view, “Spring Rain” seems to have been painted in his backyard as well. This watercolor, like “Blackbirds,” is also signed and dated in the lower right corner “-C E BURCHFIELD – 1916” in pencil. Burchfield uses simple shapes—rectangles, and triangles, to reflect the roofs of the houses and sheds. In the background, slender trees reach from the horizon line to the top of the paper. Rather than depicting each individual leaf on the trees, each cluster of leaves curve and extend out as yellowish forms. Cutting across the composition from the upper right hand corner to the center of the painting, are delicate white lines that give the illusion of a photograph capturing not the individual drops of rain, but their motion as they fall from the clouds. This, along with the pastel wash of colors and the thin, imperfect lines, contribute to the overall watery effect of the painting—as if the rain transforms the whole landscape. Burchfield’s overlapping houses and the trees in the distance, as well as the faint diagonal lines in the background connote depth and a sense of space. The point of view of the composition, looking slightly down at the buildings and out to the horizon, gives the sense of gazing out one’s window. The viewer is within one’s own space, and with that comes a sense of comfort and contentment. The feelings evoked from Burchfield’s “Spring Rain” greatly contrast those of “Crows in March,” though stylistically they share similar characteristics.

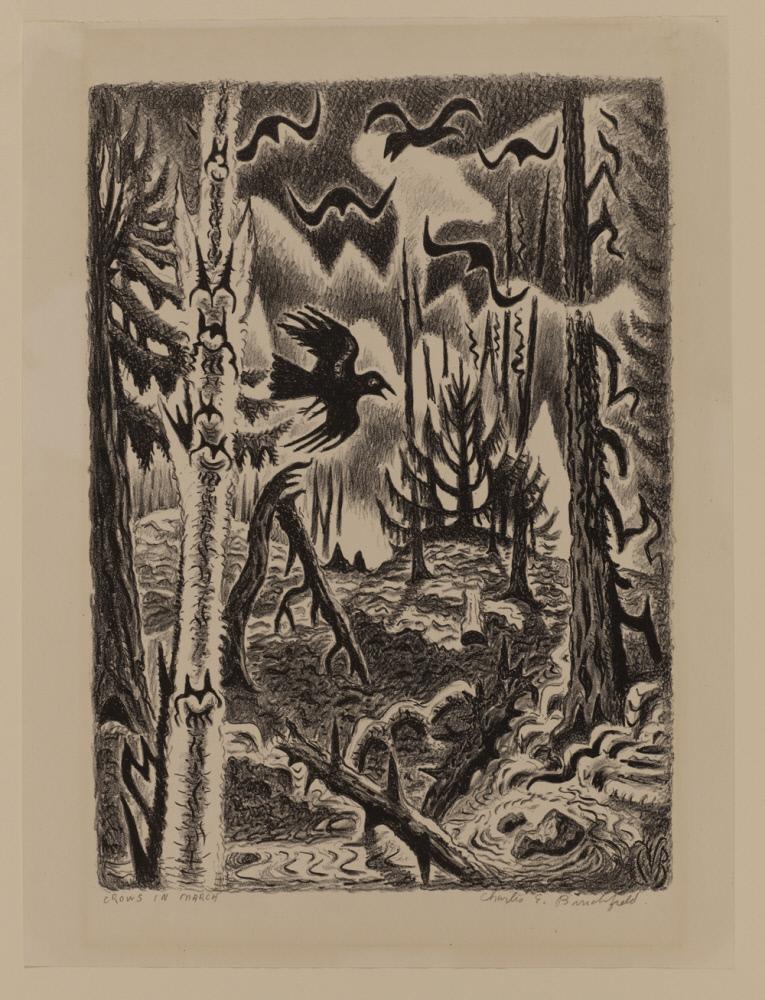

The last piece of Burchfield’s in the Wellin permanent collection is “Crows in March” (13 1/2” x 9 1/2”), a lithograph made in 1951. As one of sixty prints, “Crows in March” is part of the collections of various museums, such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Burchfield Penney Art Center, the MoMa, and the Whitney Museum. Unlike the other Burchfield works, the print uses black ink and depicts a more fantastical scene of crows, flying around an ominous, wooded landscape. Tree trunks vertically extend almost fully across the composition, with black wavy lines implying the bark’s texture. Broken trunks with pointed branches, leaning on each other and resting on the ground create an angular path for the eye to follow, up and down from the left side of the paper to the right. Scattered around the upper part of the composition are six crows in flight, one of which, closest to the horizon line, is in more detail than the rest. Compared to the two watercolors in the collection, “Crows in March” has a much more sinister impression—the contrast of dark and light, the sharp forms and the moody sky all contribute to a sense of eeriness. Though the response to this work is different than that of the watercolors, the fact that Burchfield’s lithograph elicits such a strong emotional response, exemplifies the very quality that makes his work so effective.

Charles Burchfield’s work merges representational and abstract styles as a tool for romanticizing the natural world and to induce emotional responses from the viewers. His paintings and prints at the Wellin museum reflect his style and the variation of his work at different points of his career. As an acclaimed American artist, Burchfield reflects the development of American art as an individual movement from those of other countries, and how the use of material, color, and line, harmoniously work together in his work to induce the respect and love for nature that is so important to him.

Work Cited

Alcauskas, Katherine. Innovative Approaches, Honored Traditions. Clinton: Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art, 2017. Web. http://wellin-emuseum.hamilton.edu/objects/7597/spring-rain?ctx=637f2b18-dd4f-4f6e-870d-ac4a016ede23&idx=1

“Artwork: Untitled (Camouflage design),” Burchfield Penney Art Center at SUNY Buffalo State, Web. https://www.burchfieldpenney.org/collection/object:a2006-008-450-005-untitled-camouflage-design/

“Biography: Artist to America.” Burchfield Penney Art Center at SUNY Buffalo State. Web. https://www.burchfieldpenney.org/collection/charles-e-burchfield/biography/

“Charles Burchfield.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Web. https://americanart.si.edu/artist/charles-burchfield-659

“Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield June 24 – Oct 17, 2010.” Whitney Museum of American Art. Web. https://whitney.org/Exhibitions/CharlesBurchfield