The amount of medication that Americans take to combat mental illness is astounding. In recent decades, the pharmaceutical and medical industries have convinced a large number of people that drugs are a cure-all for mental illnesses. This increased reliance on these drugs is part of rising pharmaceuticalization in the United States. Pharmaceuticalization has been defined as “the process by which social, behavioral or bodily conditions are treated or deemed to be in need of treatment, with medical drugs by doctors or patients” (Abraham 2010).

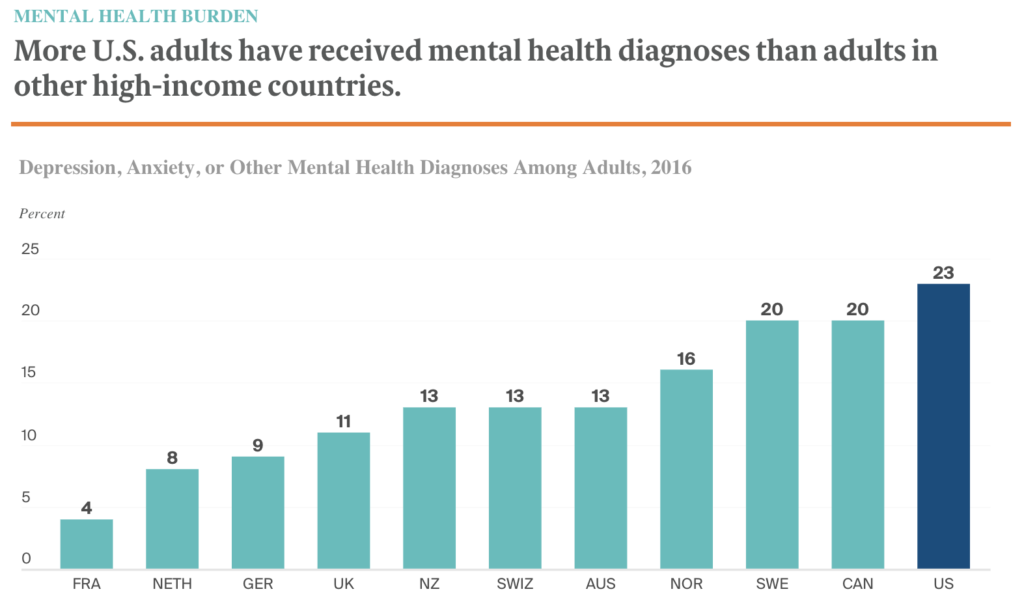

In the US specifically, there has been a growing intolerance to everyday discomforts such as “sadness” and anxiety, which has been combated through the increased prescription of drugs (Maturo 2010). This is shown through a 2016 Commonwealth survey which found that US adults have the highest percentage (23%) of diagnosed mental illness in comparison to ten other high income countries. Along with this, mental health treatments were shown to have increased by 26 million prescriptions in 2018, with 80% of that increase due to increased usage of these medications (IMS). This increased oversensitivity to uncomfortable emotions along with a redefinition of mental illness has caused a shift in the way that people diagnose and treat these diseases.

Who Is To Blame?

Both the medical community and pharmaceutical companies have played a large role in the increasing pharmaceuticalization of mental illness. Through the practices outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and increased advertising, the thresholds for diagnoses have been lowered and pharmaceutical prescriptions have increased.

The original DSM encouraged doctors to find the underlying causes of certain disorders, which typically led to treatment through therapy as well as drugs. However, since the third edition of the DSM was published in 1980, rhetoric surrounding the diagnosis of mental illness has shifted from causes to symptoms (Valleé 2010). The newer manuals list symptoms which a patient needs to exhibit to be diagnosed with a disorder which has contributed to the overall rise in pharmaceuticals. In the case of ADHD for example, certain nutritional causes and environmental toxins may contribute to the disorder (Valleé 2010). Specifically, recent studies have linked ADHD and its symptoms of hyperactivity and attention deficits with iron and Omega-3 fatty acid deficiencies along with many neurotoxins (Valleé 2010). All of these possible causes of ADHD are not mentioned in mainstream guidelines, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, which outline the treatment of this disease (Valleé 2010). Therefore, doctors tend to focus on identifying symptoms and prescribing drugs, such as Ritalin, to treat these symptoms. The shift in focus to symptoms rather than causes of mental illness has also expanded the pool of individuals with enough expertise to diagnose certain mental disorders, as they just have to be able to identify the correct symptoms.

Family doctors and physicians are increasingly making these diagnoses instead of psychiatrists; they have limited background in the field of mental disorders and therefore limited understanding in the different types of treatment ranging from pharmaceuticals to therapy (Maturo 2010; Smith 2012). Their expertise lies in treating symptoms of illnesses such as the common cold. Thus, they tend to favor drugs as treatment for mental illness as well rather than suggesting something like psychotherapy as that lies outside their typical knowledge (Maturo 2010; Smith 2012). Advertising exacerbates this issue, persuading people to contact family physicians and primary care providers with mental health concerns.

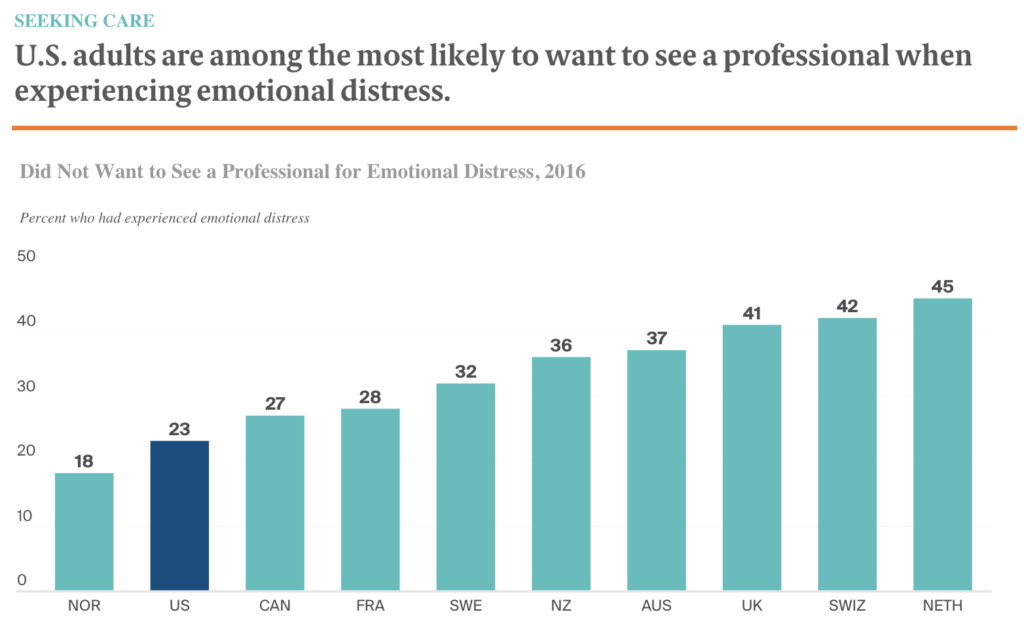

The increased involvement of the pharmaceutical industry in society through the use of advertising has led to the increased consumption of drugs, especially to cope with deviations in human emotions. With this new line of information more people, especially in the US, are more likely to self-diagnose their conditions and request medication for illnesses that have been advertised to them. Along with this, it has been shown that the majority of doctors feel pressured to prescribe the drugs specifically inquired of them (Brown 2016).

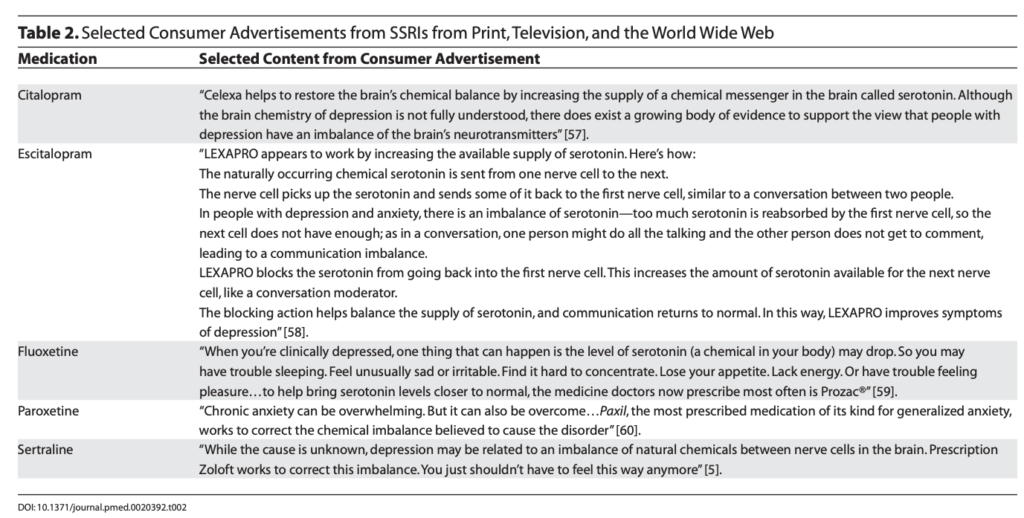

Advertising also uses seemingly scientific neuroimagery and suspect research findings to encourage the usage of certain pharmaceuticals. Specifically, in regards to depression and the advertisement of SSRIs (drugs used to increase serotonin levels), advertisements are based on research that has found serotonin as the dominant neurotransmitter affecting depressed individuals (Achamallah 2011; Lacasse 2005). To accentuate this point, typical antidepressant advertisements use computer generated graphics of the brain and depleted serotonin levels to demonstrate this biological source of depression (Achamallah 2011). However, the efficacy of SSRIs have been contested through the examination of many published and unpublished antidepressant trials, where 80% of the results were comparable to placebo (control group) results, indicating concrete evidence of the ineffectiveness of SSRIs in treating depression (Lacasse 2005). This advertised viewpoint contributes to the rise in medicalized treatment of mental illness, especially regarding prescription drugs, and decreases the likelihood of patients accepting other forms of treatment such as psychotherapy.

What Can Be Done?

Overall, the overuse of pharmaceuticals in the treatment of mental illness has lasting negative effects, physically for individuals through drug side-effects (Smith 2012), and socially through the viewing of mental illness by its symptoms. While medication is an effective and necessary treatment for many individuals, society needs to increase awareness for other treatment options such as psychotherapy and behavioral therapy, which may address the underlying causes of mental illness and do not cause drug dependence or their related side effects. All in all, more attention needs to be brought to the psychosocial and environmental causes of mental illness in order to truly start progressing towards curing mental illness for the vast amount of individuals.

References

Abraham, John. 2010. “Pharmaceuticalization of Society in Context: Theoretical, Empirical and Health Dimensions.” Sociology 44(4): 603-622 (http://www.jstor.org/stable/42857431).

Acahmallah, Natalie. 2011. “Psychotropic Medications and Direct-to-Consumer Advertising: Informative Or Irresponsible?” Journal of Ethics in Mental Health (6) (https://jemh.ca/issues/v6/documents/JEMH_Vol6_Article_Psychotropic_Medications.pdf).

Aitken, Murray, and Michael Kleinrock. 2019. “Medicine Use and Spending in the U.S.: A Review of 2018 and Outlook to 2023.” IQVIA Institute For Human Data Science (https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/medicine-use-and-spending-in-the-us—a-review-of-2018-outlook-to-2023.pdf?_=1648932330674)

Brown University. 2016. “Impact of Advertising Psychiatric Drugs.” Science Daily (www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/09/160913134000.htm).

Lacasse, Jeffery R. and Jonathan Leo. 2005. “Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific Literature.” PLoS Med 2(12): e392 (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020392).

Maturo, Antonio. 2010. “Bipolar Disorder and the Medicalization of Mood: An Epidemics of Diagnosis?” Pp. 225-242 in Understanding Emerging Epidemics : Social and Political Approaches. Vol. 1st ed. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Smith, Brendan L. 2012. “Inappropriate Prescribing.” Monitor on Psychology 43(6) (http://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/prescribing).

Tikkanen, Roosa, Katherine Fields, Reginald D. Williams II and Melinda K. Abrams. 2020. “Mental Health Conditions and Substance use: Comparing U.S. Needs and Treatment Capacity with those in Other High-Income Countries.” Commonwealth Fund (https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/may/mental-health-conditions-substance-use-comparing-us-other-countries)

Valleé, Manuel. 2010. “Biomedicalizing Mental Illness: The Case of Attention Deficit Disorder.” Pp. 281-301 in Understanding Emerging Epidemics : Social and Political Approaches. Vol. 1st ed. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.