I grew up on the Upper West Side in New York City. The blue portion of the map is the area I grew up in; it consists of mostly tall, expensive apartment buildings. I spent a lot of time playing basketball at the Frederick Douglass Playground (grayed area on the map). It is the foremost place kids hung out. Almost every afternoon was spent there. To a young kid growing up in the Frederick Douglass Houses (yellow on the map), the playground had the same function, but a different meaning. For them it was an escape.

The Douglass Houses

Only six city blocks away from my apartment is one of the largest housing projects in New York City: The Frederick Douglass Houses. It spans four full blocks, with 18 apartment buildings and more than 4,500 residents. There are no streets or avenues splitting the project; it’s frequently referred to as a “superblock.” (Douglass Houses, n.d.)

The superblock.

For kids growing up in the Douglass Houses, the playground meant something different; it meant being able to play without having to watch drug deals right in front of them. It meant having what most people would consider a normal childhood experience.

Why do the Douglass Houses matter?

Unbeknownst to me, my neighborhood is a perfect case study in urban inequality.

On Manhattan and Amsterdam Avenues between 100th street and 104th street, which the Douglass Houses are situated between, there are no restaurants. There are only small bodegas and empty storefronts.

Yet 100 yards west on Broadway, there are glass skyscrapers and a Starbucks on almost every corner.

The differences do not stop there.

On the north edge of the superblock, there is a high school: Edward A. Reynold West Side High School. Most people just call it West Side High School.

I grew up playing youth basketball in their gym; it seemed like a normal high school to me. Little did I know it is one of the worst high schools in the state.

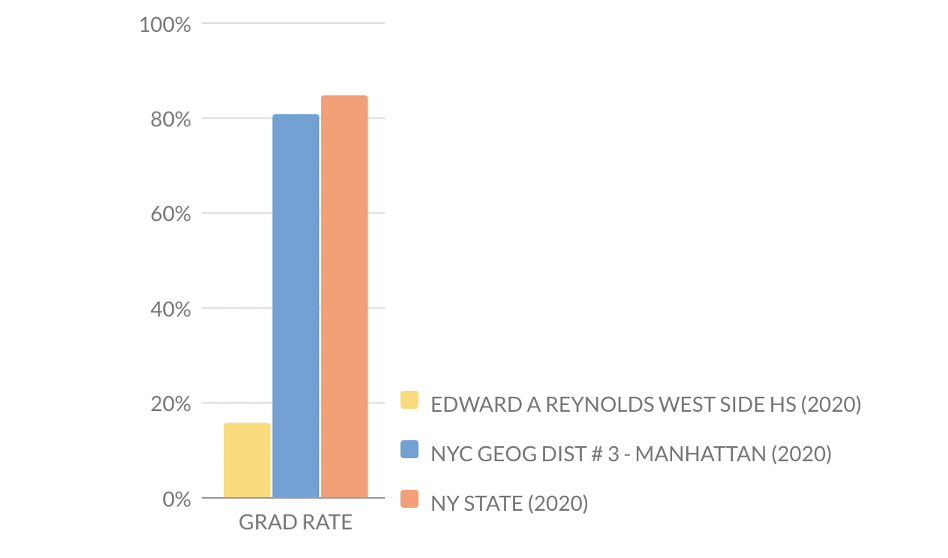

West Side High School’s graduation rate in 2020 was 16%. (EDWARD a REYNOLDS, n.d.)

(EDWARD a REYNOLDS, n.d.)

I went to a private school in the suburban portion of the Bronx called Horace Mann. My high school has a 100% graduation rate. Everyone goes to college. The same is true of my friends’ schools. It wasn’t a goal that we graduate and go to college; it was a requirement.

The theme of schools failing underprivileged students extends across urban areas in America, too.

A study completed in 2010 found a strong relationship between socio-economic status and educational achievement in urban areas across the United States. A student from a high socio-economic class is 6 times as likely to complete a college degree as a student from a lower class background. (Rumberger, 2010)

The data is there at West Side High School, too. The class of 2020 at West Side High School was 165 students. 146 of them were deemed as “economically disadvantaged.” They can’t disclose how many of the students are from the Douglass Houses, but it’s certainly a significant section of the student body. (EDWARD a REYNOLDS, n.d.)

In the class of 2020, West Side High School had zero students achieve Advanced Regents, a measure of academic success across New York. Other schools in Manhattan averaged 30% of their students achieving that designation. This explicitly tells us that students with significant economic issues are performing worse than their economically better-off peers. (EDWARD a REYNOLDS, n.d.)

It has been established in recent studies that economic inequality is passed down from generation to generation. Parental earnings are a strong indicator of a child’s future economic status. For example, a child growing up in the Douglass Houses is likely to earn a similar amount of money as their parents. It is unlikely that they will earn enough money to leave the Douglass Houses. This creates a cycle of economic hardship that is incredibly hard to break out of. (Bowles & Gintis, 2002)

An important part of this experience has been diving deep into my own community. I was friendly with kids from the Douglass Houses; we’d play basketball together every day. I never understood what they were going through once they left the playground. I never thought about how I’m 6 times more likely to obtain a college degree than they are. I was witnessing deep class division, but I did not know it.

My neighborhood is not unique; there are tons just like it in cities across the country. I encourage you all to take a look at your own communities. I promise that you’ll never look at it the same again.

References

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2002). The Inheritance of Inequality. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), 3-30. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533002760278686

Douglass Houses. (n.d.). New York City Housing Authority. Retrieved May 4, 2021, from https://web.archive.org/web/20090706045248/http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/html/developments/mandouglass.shtml

EDWARD A REYNOLDS WEST SIDE HS GRADUATION RATE DATA 4 YEAR OUTCOME AS OF AUGUST 2020. (n.d.). New York State Education Data. Retrieved May 4, 2021, from https://data.nysed.gov/gradrate.php?year=2019&instid=800000046826

Rumberger, R. W. (2010). Education and the reproduction of economic inequality in the United States: An empirical investigation. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), 246-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.07.006