By Bennett Hauck

Of the 147,071 people currently in the United States federal prisons system, 146,825 are men, and 10,838 are women. 65,895 of the 147,071 are imprisoned due to drug offenses, which include possessing, manufacturing, or selling illegal substances (Federal Bureau of Prisons, 2023). These men and women are imprisoned as a punishment, not for rehabilitation purposes. Repercussions for drug offenses intensified following Ronald Reagan’s announcement of the war against drugs in 1982. Following the introduction of drug related policy, drug-related arrests and violations increased nearly threefold from 1982-2011 and the number of incarcerations quadrupled (Jordan Woods 201, p. 2-3 ). Meanwhile, drug use and drug-related deaths soared. 2016 saw around 64,000 deaths due to overdoses in the United States (Kristof, 2017).

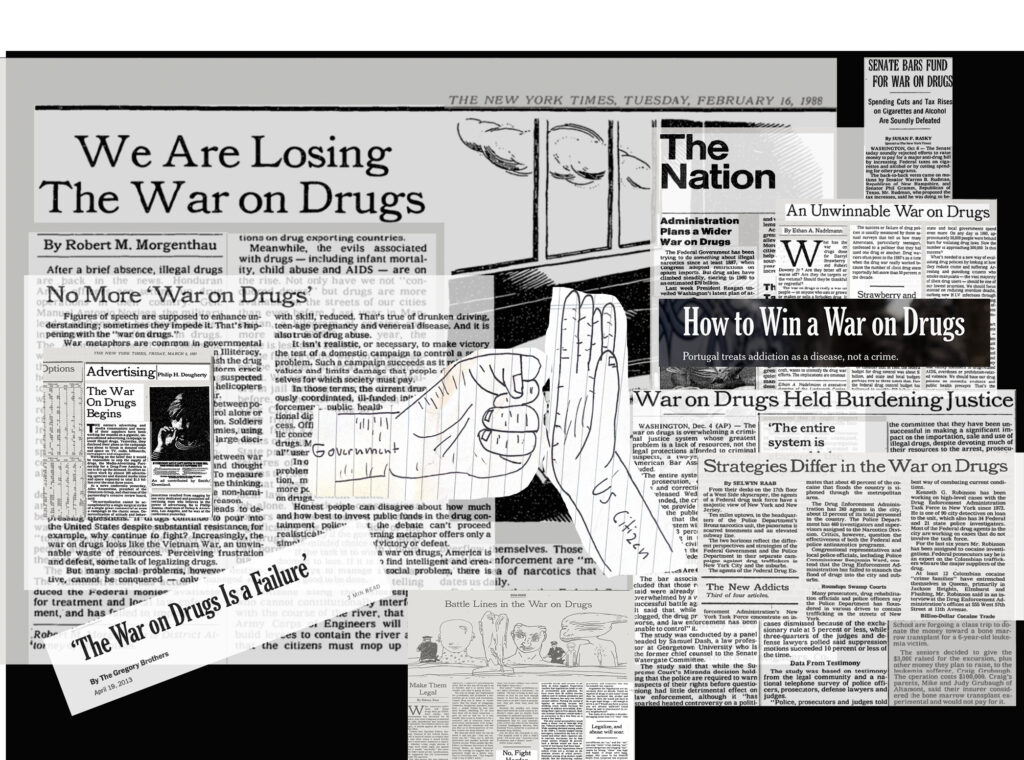

The War on Drugs in the United States can undoubtedly be marked as a failure. It has instead seen an increase in racial targeting of people of color, black men in particular, the imprisonment of first-time users, and placing the mode of treatment into the hands of the criminal justice system (Kristof, 2017).

The United States does not stand alone in its problematic situation with drug use, but its reluctance to change policy as a major western power is becoming more pronounced as other western countries shift positioning Portugal is a Western country that has utilized a decriminalization model, which does not legalize drugs but drops potential charges from being placed on those found carrying or purchasing user amounts of drugs. Instead, a nationwide system built around drug reform centers and drug consumption sites has led to a drop in drug arrests, smaller jail populations, and fewer overdoses (Jordan Woods 2001, p.15). This model can be visible in other countries like Germany and the Netherlands.

Victims in the War on Drugs

We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news.

Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.”

Vera Institute of Justice

- John Ehrlichman, Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs under President Richard Nixon

In 1991 black people accounted for 12% of the entire population within the US but made up 40% of the drug arrests and over 60% of the imprisonments for drug offenses. This information and its connection to race-targeted arrest are made even more apparent when a national survey from the same year shows that the percentage of users nationwide showed that 39% of both white and black Americans were users (Chambliss, 1995, p.106). Today, black men and women account for 13% of the entire population (61,183 people in total), while still accounting for 38.5% of the prison population. Hispanic prisoners also make up a staggering 30.2% of the total federal prison population while only accounting for 19% of the total U.S. population (Federal Bureau of Prisons, 2023).

The United States’ drug system targets not only people based on race but also first-time and low-level users, grouping them under the same conditions as more dangerous or serious cases. In 1994, 36.1%, (16,316), of all prisoners sentenced for drug offenses were low-level offenders served on average around 5 ¾ years (US Department of Justice 1994, p. 71). Due to suffering jail time, a person can then lose their right to vote, not only, for the duration of their incarceration period but, in some cases, permanently (Bobo, Thompson, 2006, p.454).

Portugal’s Experience with Decriminalization

Portugal uses a decriminalized system to fight and combat drug use. In the 1980s and 1990s, Portugal saw a drastic increase in drug-related issues connected to heroin and cocaine use (Jordan Woods 2001, p.15). In response, their parliament opted for a harm-reduction strategy that led to the creation and implementation of law 30/2000 in 2001.

This law ended the use of penal sanctions for drug possession and introduced a system of referrals to Commissions for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction (CDTs) (Stevens and Hughes 2007, page 1 ). A commission was created in each of the 18 districts in Portugal that held meetings to determine what the individual needs regarding assistance or guidance (Jordan Woods 2011, p 17).

With over 20 years of implementation, the success of law 30/2000 can be seen by comparing data from before and after its introduction. Deaths related to drug use dropped from a total of 369 in 1999 to 152 in 2003 (University of Kent, 2007). The burden on the prison system also dropped following decriminalization. The number of prisoners doing time for drug charges fell from 44% of the total inmate population in 1999 to only 28% in 2005. In 2001 there were 7,592 charges for drug consumption compared to 2007, when there were only 6,026 referrals to the CDTs. This then helped alleviate stress and funding to the prison systems and police.

A change in drug policy also shifted the rate of incarceration in Portugal. From 2001 to 2005, the prison density (prisoners per 100 prison places) fell from 119 to 101.5 (Hughes and Stevens 2010). The police, on the other hand, could shift more energy towards the entry of drugs into the country. Between the years of 1995-1999, when compared to 2000-2004, the amount of “heroin, cocaine, cannabis and ecstasy seized” through large scale busts, by police increased by 100% (University of Kent, pg. 3). Although not definitive, this change in drug larger scale drug seizures is suggestive of the power of allocating funds due to a change in policy.

Germany’s and the Netherlands’ Decriminalization Policy

The German government’s policy towards drug control had been largely prohibitionist (Anderson 2012, p. 5). Like in the US, during the end of the 20th century, drug offenders in Germany occupied a large portion of the prison system. In 1989, 10% of the male prison population and 30% of the female population were imprisoned on drug offenses, with marijuana and heroin accounting for the majority of offenses. (Fischer 1995 p. 391) To deal with this, Germany introduced a decriminalized drug system in the 1990s. They recently passed an additional national Drug and Addiction policy in 2012. Following a steady rise in drug use and incarceration rates during the mid to late 20th century. The four pillars of the approach are:

- prevention

- counseling and treatment and help in overcoming addiction

- harm reduction measures

- supply reduction (German Country Drug Report 2019)

Germany’s approach is to create a system of prevention and treatment centered around rehabilitation centers and designated safe zones for users. Despite still utilizing police presence to enforce the law, the pressure is more on care than punishment.

Following the introduction of the decriminalization policy, the number of first-time heroin users entering treatment facilities dropped from 37.1% to 19.6% between 1999 to 2009, representing a decrease in the number of people arrested as well as using heroin (Anderson 2012, p.13).

Germany’s policy still views unauthorized drug possession as a criminal offense or intent to distribute as illegal. Like in Portugal, the fault must be decided before a respective municipality.

The Netherlands still follows the guidelines laid out by Opium Law of 1976 which places emphasis on pursuing harder drugs while taking a less punitive stance on possessing and using softer drugs like marijuana. With the designation of smoking areas, where you can buy and use weed in coffee shops, visible public usage of drugs is kept at a minimum. (Anderson 2012, p. 4) This decriminalization of softer drugs allows police forces to focus more on root causes and go after traffickers.

Through a government-sponsored site, the Dutch government’s approach to drug treatment saw a drop in first-time heroin users from 29% to 5.9% between 1999 and 2009 (Anderson, 2012, p.13).

How New Policy can Lead to Change

If a shift is to happen in the United States, it will be based around policy change. In 2021, the Biden Administration helped put pressure on the National Drug Control Policy to, for the first time in a generation, spend more money on drug treatment than on law enforcement (The Editorial Board). Despite any slight shifts, the core issues and the lasting effects of the war on drugs still remain, and so does the number of Americans dying from overdoses. A staggering 98,268 people died in 2021 in the United States by what is described as “preventable” overdose, an all-time high (National Safety Council). Following Portugal’s drug reform, the number of citizens dying from overdoses dropped by 85%, the lowest in Western Europe. (Kristof)

Outdated policy in the US included laws like the Crack House Statute, which subjects anyone to penalties under federal law, who maintain a house for the purpose of using illicit drugs. Enacted during the height of the crack epidemic but is currently blocking the introduction of supervised consumption sites like the ones in Portugal. The Len Bias Law, signed by Ronald Reagan, also exposes anyone involved in or around an overdose to face prison time, which prevents needed action taken by those around an individual (The Editorial Board).

The War on Drugs is not over, nor is the discussion about the right steps to take to ameliorate it. The side effects are mass incarceration, drug overdose, enforcing a racist system, and the inability to treat those deeply affected are prevalent. Fears and doubts around what decriminalization can do can quickly be dissolved when looking at other Western and industrialized nations who, by utilizing this system, have created a better reality for their affected individuals.

Citations

Anderson, Steve (2012) “European Drug Policy: The Cases of Portugal, Germany, and The Netherlands,” The Eastern Illinois University Political Science Review: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 2.

Available at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/eiupsr/vol1/iss1/

Bobo, Lawrence D., and Victor Thompson. “Unfair by Design: The War on Drugs, Race, and the Legitimacy of the Criminal Justice System.” Social Research 73, no. 2 (2006): 445–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40971832.

Chambliss, William J. “Another Lost War: The Costs and Consequences of Drug Prohibition.” Social Justice 22, no. 2 (60) (1995): 101–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29766881.

Board, The Editorial. “America Has Lost the War on Drugs. Here’s What Needs to Happen next.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 22 Feb. 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/22/opinion/harm-reduction-public-health.html?searchResultPosition=3.

European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Germany – Emcdda.europa.eu. 2019,https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/media/publications/documents/11334/germany-cdr-2019.pdf.

Federal Bureau of Prisons 2023. “Drug Offenses in Federal Prison.” BOP Statistics: Inmate Offenses, 4 Mar. 2023, https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp.

Fischer, Benedikt. “Drugs, Communities, and ‘Harm Reduction’ in Germany: The New Relevance of ‘Public Health’ Principles in Local Responses.” Journal of Public Health Policy 16, no. 4 (1995): 389–411. https://doi.org/10.2307/3342618.

Hughes, Caitlin Elizabeth, and Alex Stevens. “WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE PORTUGUESE DECRIMINALIZATION OF ILLICIT DRUGS?” The British Journal of Criminology 50, no. 6 (2010): 999–1022. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43610822.

Jordan Blair Woods, “A Decade after Drug Decriminalization: What Can the United States Learn from the Portuguese Model,” University of the District of Columbia Law Review 15, no. 1 (Fall 2011): 1-32

Stevens, Alex, and Caitlan Elizabeth Hughes. “ The Effects of the Decriminalization of Drug Use in Portugal.” Kent Academic Repository , Dec. 2007, https://kar.kent.ac.uk/13325/1/BFDPP_BP_14_EffectsOfDecriminalisation_EN.pdf.pdf.

United States Department of Justice. FEDERAL DEFENDER FACT SHEET: Flawed U.S. Sentencing Commission Report Misstates Current Knowledge. 4 Feb. 1994, https://www.fd.org/sites/default/files/criminal_defense_topics/essential_topics/sentencing_resources/useful_reports/1994-doj-study-part-1.pdf.