Tinder is the most popular dating app in the world, with 7.8 million Americans who are active monthly users (Verto Analytics 2019). The interface of this app provides a range of profiles that can either be swiped right to show disinterest or swiped left to demonstrate attraction. When two people swipe left on each other, they “match” and are allowed to start a conversation with each other.

The app has successfully provided greater agency and efficiency in people’s sexual-romantic lives, but not everyone benefits from it equally (Hobbs 2016, Hoff 2019). Tinder’s interface and algorithm supports users in acting according to their unconscious racist bias, which is chiefly detrimental to racial minorities. In fact, all people of color (POC) are more likely to be turned down compared to their white counterparts, with Black users being the ones who suffer the most amount of rejection (Chopik & Johnson 2021).1

Unconscious Swiping, Unconscious Bias

“I get about 5-7 matches per day (not swiping right on every girl) so that’s prolly okay. My white roommates get 99+ lmao”

YakEvir, Asian man’s experience on Tinder (Oishi 2019)

Tinder’s platform elicits unconscious swiping. The app profits from maximizing the attention it captures from the users (Zulli 2018). Considering that the average attention span is decreasing, the app only requires people to “glance” rather than “gaze” at profiles (Rudder 2015, Zulli 2018: 110). For instance, the app limits users to a 9 photos and 500 character bio. This encourages people to be succinct in their presentation and to quickly access potential partners, which further automate the swiping experience. Research by Sociologist Gregory Narr (2021) shows that people have a hard time describing why they were swiping left on certain profiles, which points to how swiping becomes an unconscious decision.

Unconscious swiping creates fertile soil for unconscious racist bias to flourish. Although the majority of White Americans consider themselves non-racist, they still demonstrate unconscious racist bias in Implicit Association Tests (Greenwald et al. 2009). Akin to IAT images, when people are encouraged to swipe unconsciously, they are more prone to be guided by their unconscious racist bias (Oishi 2019). Instead of considering people’s content, the profiles become part of an aesthetic experience. People deemed as “aesthetically pleasing”, which is often rooted in White colonial beauty standards, capture more attention than other users and have a more pleasurable experience with dating apps (Sui & Lui 2009, Oishi 2019).

An Algorithm That Reinforces Racism

Tinder then recommends potential matches based on people’s perceived “attractiveness,” which amplifies racist outcomes (Powering Tinder, 2019). People with a high “attractiveness” score receive more and faster “highly desirable” recommendations (Narr 2021). This algorithm excludes people that are not considered attractive to the majority of users, which chiefly affects POC who do not fit conventional White beauty standards (Narr 2021). Tinder’s algorithm thereby replicates and reinforces people’s unconscious racism, which further marginalizes racial minorities.

Advocating For An Ethical Tinder

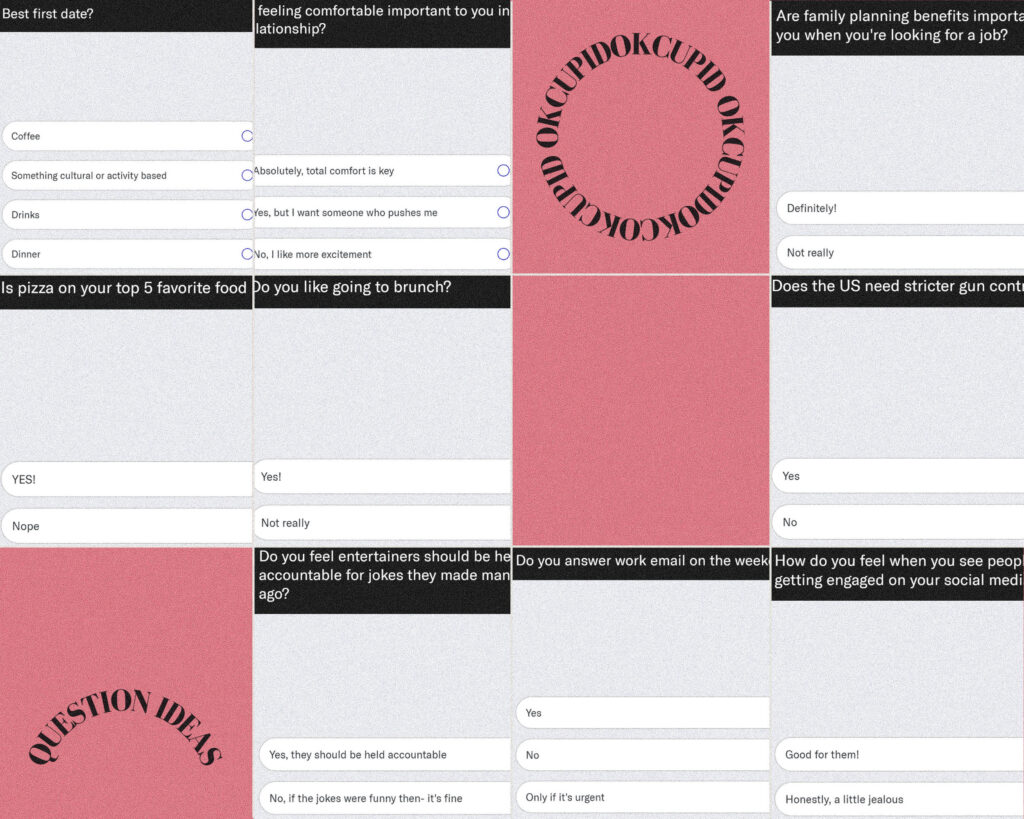

Collage with some of the questions that OKCupid uses to guide matches on its platform.

Tinder probably did not create its interface and algorithm to intentionally target POC. However, any structure in society that is complacent to racism perpetuates oppression. Instead of using an algorithm based on perceived “attractiveness,” Tinder could use multiple-choice answers to guide people’s matches. Just like dating app OkCupid, people would be able to determine which questions they want to answer and how they want their matches to respond to those questions (Narr 2021). Meanwhile, Tinder users should resist the urge to automatically swipe and reflect on how racial patterns in their swipe can convey racist imperatives. We are all responsible for fighting against the racism in ourselves and pressuring companies to advocate for anti-racist measures.

1It is important to recognize that most dating apps encourage implicit racist bias in their interfaces (Oishi 2019). I specifically analyze Tinder because it is the most used dating app and because its algorithm corroborates racist outcomes more significantly than its competitors (Oishi 2019).

References

Chopik, W.J. and Johnson, D.J. (2021) “Modeling dating decisions in a mock swiping paradigm: An examination of participant and Target characteristics,” Journal of Research in Personality, 92, p. 104076. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104076.

Dovidio, J.F., Gaertner, S.L. and Pearson, A.R. (2016) “Aversive racism and contemporary bias,” The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Prejudice, pp. 267–294. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316161579.012.

Greenwald, A.G. et al. (2009) “Understanding and using the implicit association test: III. meta-analysis of predictive validity.,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), pp. 17–41. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015575.

Hobbs, M., Owen, S. and Gerber, L. (2016) “Liquid love? dating apps, sex, relationships and the digital transformation of intimacy,” Journal of Sociology, 53(2), pp. 271–284. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783316662718.

Lorenz-Spreen, P. et al. (2019) “Accelerating dynamics of collective attention,” Nature Communications, 10(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09311-w.

Narr, G. (2021) “The uncanny swipe drive: The return of a racist mode of algorithmic thought on dating apps,” Studies in Gender and Sexuality, 22(3), pp. 219–236. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15240657.2021.1961498.

Oishi, T. (2019) “Tinder-ing Desire: The Circuit of Culture, Gamified Dating and Creating Desirable Selves,” Washington University Research Works Archive [Preprint]. Available at: https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/handle/1773/45157/Oishi_washington_0250E_20985.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed: 2023).

Powering tinder® — the method behind our matching (no date). Available at: https://www.help.tinder.com/hc/en-us/articles/7606685697037-Powering-Tinder-The-Method-Behind-Our-Matching (Accessed: March 31, 2023).

Rudder, C. (2015) Dataclysm who we are (when we think no one’s looking). London: Fourth Estate.

Sui, J. and Liu, C.H. (2009) “Can beauty be ignored? effects of facial attractiveness on covert attention,” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16(2), pp. 276–281. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3758/pbr.16.2.276.

van Hooff, J. (2019) “Swipe right? tinder, commitment and the commercialisation of intimate life,” Romantic Relationships in a Time of ‘Cold Intimacies,’ pp. 109–127. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29256-0_6.

Verto Analytics (2019) U.S. dating apps by audience size 2019, Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/826778/most-popular-dating-apps-by-audience-size-usa/ (Accessed: April 17, 2023).

Zulli, D. (2017) “Capitalizing on the look: Insights into the glance, attention economy, and Instagram,” Critical Studies in Media Communication, 35(2), pp. 137–150. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2017.1394582.