To Be Diagnosed with Pediatric Cancer

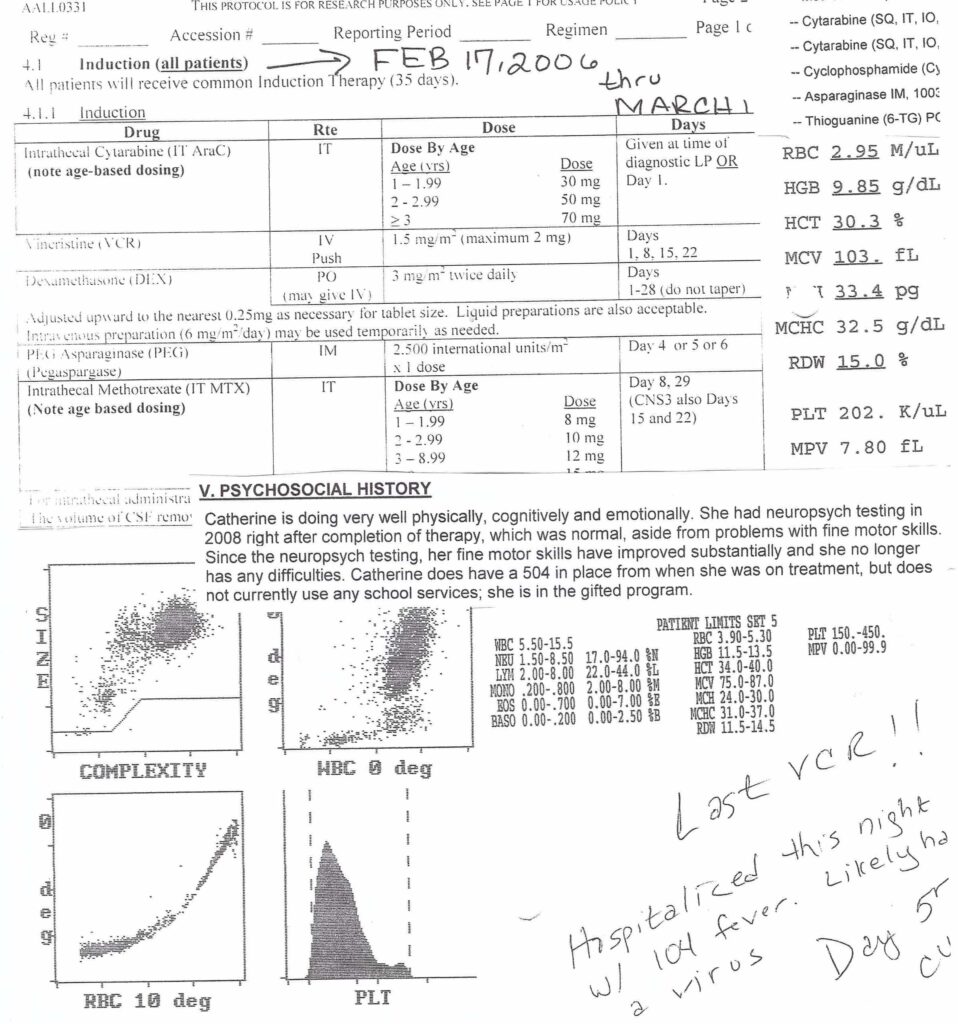

“Your child has cancer.” These are four words that a family never wants to hear. But cancer is a reality for nearly 400,000 children each year (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital), including myself in 2006. With this diagnosis comes months and years of treatment and surgeries. Patients are treated with chemotherapy drugs that sound as if they are straight out of a science fiction movie, such as Cytoxan, Decadron, and Methotrexate.

Advancements in medicine and technology have led to 80% of pediatric cancer patients becoming long-term survivors; however, 65% to 75% percent of childhood cancer survivors face at least one late-term effect. These late–term effects include organ system malfunction, neurological deficits, and physical distress (Mertens et. al 2013). The physical and mental impairments that pediatric cancer survivors face pose difficulties in their social lives and education.

The Lasting Social Effects of Cancer

Being a pediatric cancer survivor is an identity that survivors carry throughout their lives. Despite the courage and pride that come with this identity, being a cancer survivor can also be a lonely experience (Jones et al. 2011). Survivors may feel as though none of their peers understand what they have endured throughout their cancer experiences. Growing up as a leukemia survivor, I often felt isolated as none of my friends knew what an oncologist was and what I called the “yucky medicine” was like. This sense of isolation creates a division between pediatric survivors and their peers as survivors learn to cope with their identities.

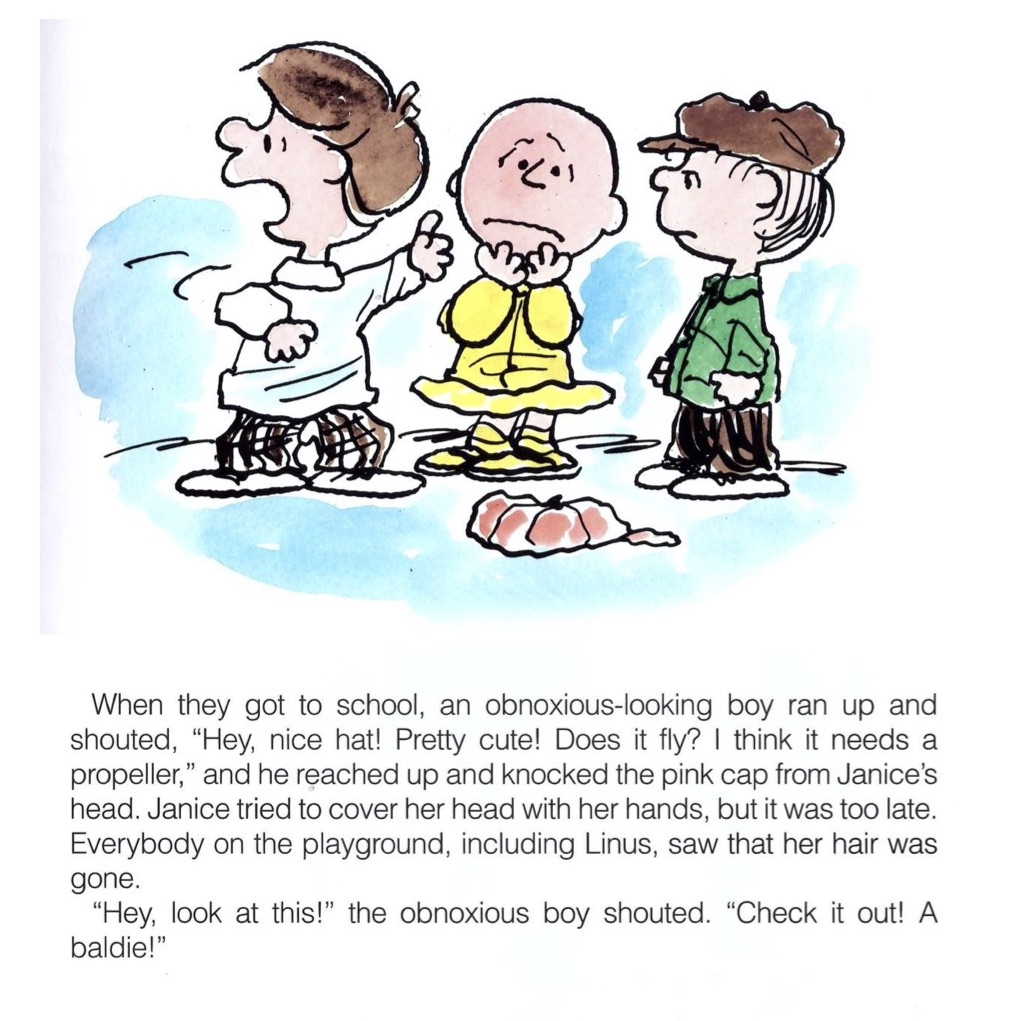

Furthermore, returning to social environments, such as school, can be stressful as survivors feel that they will be judged for their physical impairments. While I was going through treatment, I received rude remarks from my peers about my bald head, calling me a “baby.” This fear of being judged can make it difficult for cancer survivors to forge relationships with those around them (Morales 2021). In fact, survivors significantly reported more frequently that they had no close friends and did not choose to spend their leisure time with the friends they did have (Gurney et al. 2009).

Survivors’ Education Trajectories

Pediatric cancer survivors tend to need extra special education services in their education. These special services help students whose cancer treatment left them with memory loss, sensory issues (i.e. difficulty hearing or seeing), learning disabilities, and chronic fatigue. The long-term side effects of cancer treatment can lead students to miss an ample amount of school. Those diagnosed with brain tumors, leukemia, or Hodgkin’s lymphoma were more likely to require special education services compared to other cancers such as osteosarcoma and melanoma. Personally, I never needed the personalized services my school provided me, but I was still monitored for any learning disabilities.

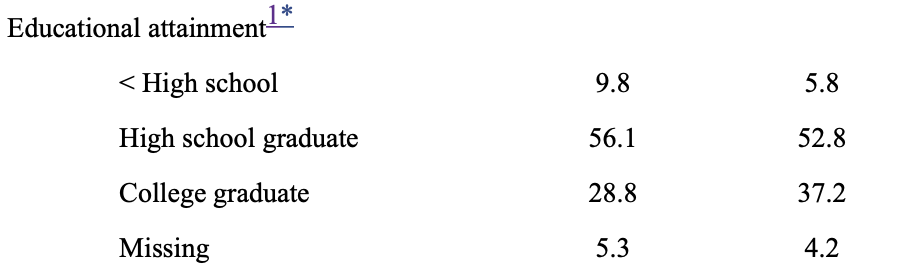

In studies on pediatric cancer survivors and their educational outcomes, siblings have been used as control groups. A 2009 Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) found that among 12,430 survivors, 23% utilized special education services while out of 3,410 siblings, only 8% needed extra support in school (Gurney et al. 2009). While pediatric cancer survivors tend to need extra support in school, survivors have a high rate of college enrollment, but are still lower than their siblings.

While pediatric cancer survivors were less likely to attend college than their siblings, the fact that a considerable amount of childhood cancer survivors will go to college is a promising statistic. Though pediatric cancer survivors are able to acquire high paying jobs through obtaining college degrees, their road to success is littered with obstacles created by the sickness they have overcome.

Bibliography

“Childhood Cancer Facts.” St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Retrieved February 25, 2022 (https://www.stjude.org/treatment/pediatric-oncology/childhood-cancer-facts.html).

Gurney, James G., Krull, Kevin R., Kadan-Lottick, Nina, Nicholson, H. Stacy, Nathan, Paul C., Zebrack, Brad, Tersak, Jean M., Ness, Kristen K. 2009. “Social Outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Cohort.” Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 27(14): 2390–2395.

Jones, Barbara, Parker-Raley, Jessica, Barczyk, Amanda. 2011. “Adolescent Cancer Survivors: Identity Paradox and the Need to Belong.” Qualitative Health Research. 21(8): 1033-40.

Mertens, A., Brand, S., Ness, K., Li, Z., Mitby, P., Riley, A., Patenaude, A. and Zeltzer, L., 2013. Health and Well-Being in Adolescent Survivors of Early Childhood Cancer: a Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. 23(3): 266–275.

Morales, Alba. 2021. “A Social Approach to the Effects of Childhood Cancer: a Review of Relevant Social Contexts.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention. 10(2): 39-46.

Schultz, Charles M. 1990. Why, Charlie Brown, Why?: A Story About What Happens When a Friend Is Very Ill. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.