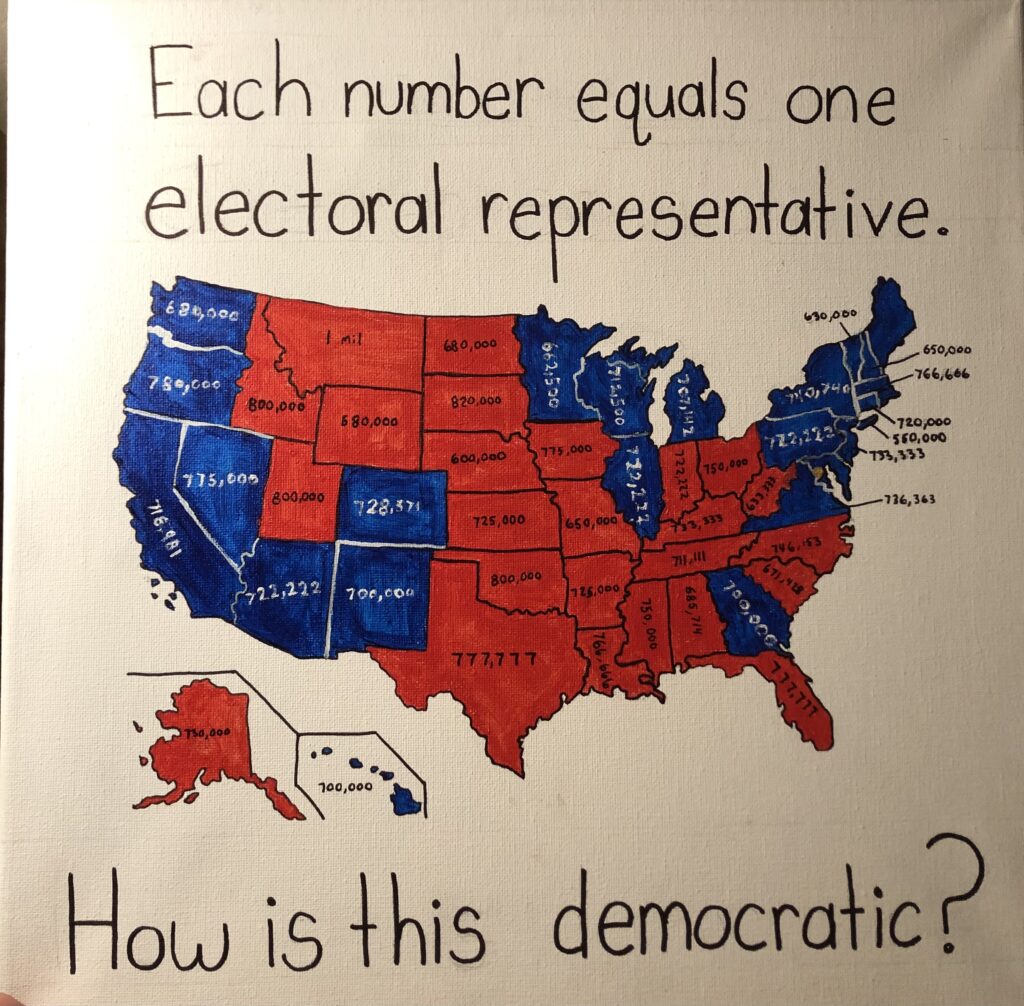

Pictured: US map colored by party association in the 2020 presidential election. Each state contains the number of votes needed to equal one of their electoral representatives.On average, democratic states needed ~261,437.91 votes to win one electoral representative, while Republicans needed ~318,665.91 (~57,527.61 more on average) in the 2 020 election.

The structure of the electoral college perpetuates an unequal system in the American presidential race. If you are 18 or over, you have likely already participated in this ineffective system. The number of representatives is not equally proportionate to the overall state population, meaning some votes are worth more than others. For example, a Californian electoral vote represents ~718,363 people, while a Michigan electoral vote represents ~624,187 people. As a result, the citizens of Michigan have more of a say proportionately in the election than citizens in California. This phenomenon is called malapportionment, and perpetuates inequality all across the nation.

The electoral college contradicts the fundamentals of democracy that America is founded on.

The system “has the potential to undo the people’s will at many points in the long journey from the selection of electors to counting their votes in Congress.”

(Edward 2019, pg. 37)

The electoral college allows a president to be elected regardless of the country’s will, at times producing an election with a contradictory majority and electoral vote. This has happened several times over our country’s history, including Andrew Jackson, Samuel Tilden, Grover Cleveland, Al Gore, and most recently in the 2016 election when Donald Trump won despite losing the majority to his opponent, Hillary Clinton. It is no coincidence that each candidate that has lost despite winning the majority has belonged to the Democratic Party.

The electoral college allows some votes to be valued above others, violating our basic democracy, as Jon Elster argues, “as a matter of first-order political theory that democracy is simple majority rule, based on the principle of ‘one person, one vote.’”

(Edward 2019, pg. 38)

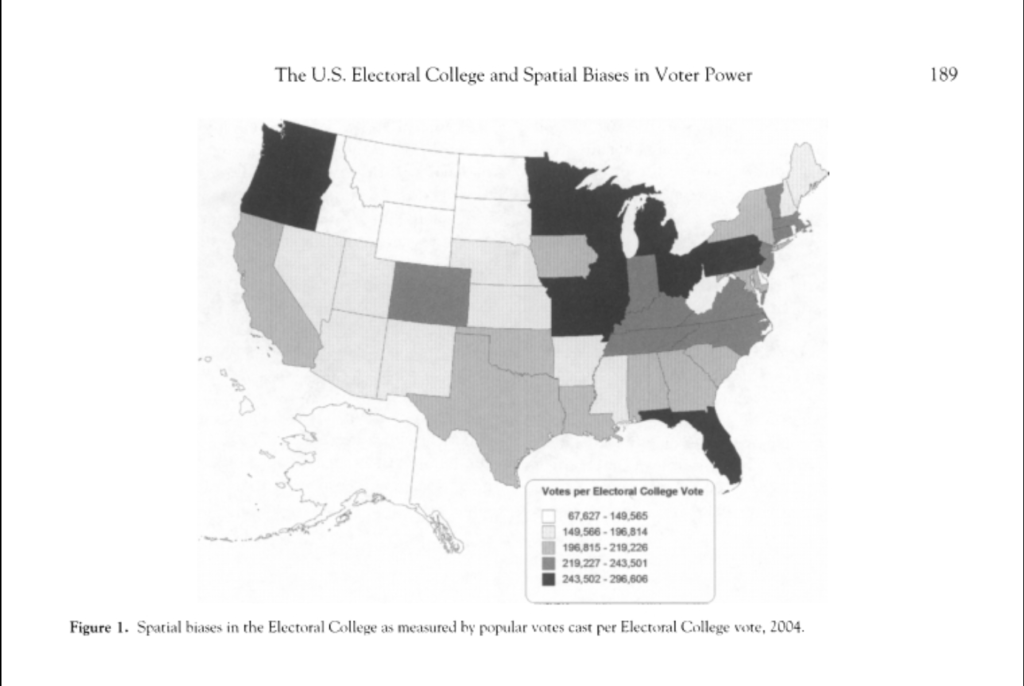

One can see how differently votes are weighed in figure 1 (Warf 2009, pg. 189) below, in which spatial biases clearly violate Elster’s democratic principles.

Perhaps the most obvious example of inequity within the electoral college is the exceptions surrounding the District of Columbia. It serves as a special federal district, not a state, and therefore does not share the same voting rights, despite containing 692,683 citizens. The 1961 23rd constitutional amendment entitles the District to the same number of electoral votes as that of the least populous state in the election of the president and vice president. In 2020, this amendment conflated DC to Wyoming, the least populous state with 580,000 residents. This is gross inequality.

A Gallup Poll stretching back 50 years suggesting that 61% of Americans would choose direct election over the electoral college,

“‘There is little question that the American public would prefer to dismantle the Electoral College system, and go to a direct popular vote for the presidency.”

Jon Elster

Most Americans agree that an amendment to the Constitution is essential in achieving a true democratic electoral process.

The electoral college is also a pillar in maintaining the two party system. Since the electoral college primarily deficits more densely populated, urban states like California and New York, people of color, whose presence is statistically heavier in more densely populated states, are habitually underrepresented. The opposite inequality is reflected in the 2020 election. As it was a democratic victory, with the highest voter turnout in the country’s history, this high turnout in addition to a few key states flipping made the electoral college work in favor of the winning party. On average, Republicans needed ~57,527.61 more votes than Democrats to win one representative.

This inequity of representation is conflated by the two party system. Due to their effectively only being two options for president, the chosen democratic and republican representative, many American voters choose ‘the lesser evil.’ Due to the limited system, voters are confined in their choices, creating extremely heterogeneous parties. This promotes extreme polarization between the parties, and allows far less individualistic views. By replacing the electoral college with direct election, more parties would be able to emerge, creating more homogenous politics,

“As parties became more internally homogeneous, politics would become more ideologically charged, and citizens might be less willing to accept the result when more appeared to be at stake.”

(Edward 2019, pg. 175)

With direct election, citizens may be less willing to settle, allowing more views to be expressed and valued in politics. Direct election in place of the electoral college is vital for true equity in America.

Bibliography:

- Warf, Barney. “The U.S. Electoral College and Spatial Biases in Voter Power.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 99, no. 1, 2009, pp. 184–204. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25515184. Accessed 31 Mar. 2021.

- III, Edwards George C. Why the Electoral College Is Bad for America. Yale University Press, 2019.