“Are you, like, a terrorist?”

This question came out of the mouth of a pale, 9-year-old boy. I, a marginally less pale 10-year-old girl, had just told him my mother was from the Middle East. And his response had taken me completely by surprise. But it was not the first time I had felt othered by and confused about my identity, and it certainly would not be the last.

My mother immigrated to the U.S. from Turkey with her family, and I was one of the first children born thereafter in the United States. From a young age, I had always thought I was White. I had skin that was pale enough, and both of my parents seemed White to me. As I grew up, I received comments from my White peers that my skin was visibly more tan than theirs, if only slightly, or that my eyebrows were much thicker, and I never thought much of it. It was not until that boy had asked me if I was a terrorist that I had started to understand that I was not like other White children, and my mother was not like their White mothers.

Our experience is not an isolated one. Many people of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) or Arab descent in the United States struggle with finding a label for themselves while understanding that they are distinctly not White in many Americans’ eyes. A recent survey found that 84% of MENA people felt that they were an ethnic minority (Awad, Hashem, and Nguyen 2021:115-230). Another study noted that White people and MENA people both associate MENA traits like religion, names, and ancestry with being distinctly MENA rather than White (Maghbouleh, Schachter, and Flores 2022).

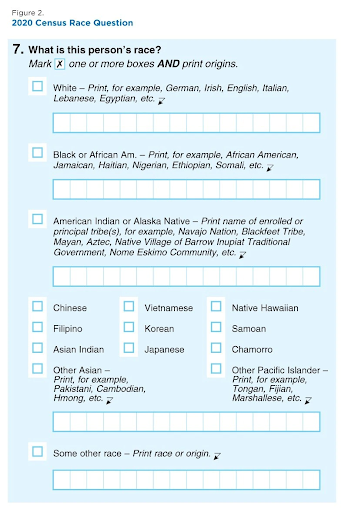

So why, then, are MENA people still counted as White on the U.S. Census? On the most recent U.S. Census, there were six categories for race: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, with an additional category, called Some Other Race for those that did not identify with the options provided (Jensen et al. 2021).

Xenophobic Prejudice, Discrimination, and Inequality

“Although many, but not all, Arabs phenotypically can pass as White, their lives are racially marked, as they are perceived and treated as non-White.”

Abboud, Chebli, and Rabelais 2019

This exclusion of MENA people from the U.S. Census has further implications than MENA people feeling unacknowledged and invalidated by the U.S. public. The U.S. Census Bureau includes race on the Census so that it can collect statistics on people of different backgrounds in order to determine which are disadvantaged and in particular need of aid.

One study published in the 2019 edition of the American Journal of Public Health called upon the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) to declare the MENA/Arab population of the United States as a disparity population. The NIMHD is an organization that sponsors and conducts research on minority health in addition to raising awareness about disparities between populations. Were they to begin spreading awareness about the struggles of MENA people in the United States, the study’s message in question would gain a larger audience and potentially influence the result of the 2020 census. The contributors to the study argue that “Although many, but not all, Arabs phenotypically can pass as White, their lives are racially marked, as they are perceived and treated as non-White,” (Abboud, Chebli, and Rabelais 2019). In essence, being MENA operates like a race but is not included as a racial category because while there has been research on this population, research does not track disparity. Thus the government cannot allocate additional resources to MENA people.

Additionally, another recent study found that the MENA rate of fair or poor health status almost mirrors that of African American and Latino populations in several metropolitan areas around the United States and that many MENA people are at increased risk for food insecurity and financial strain (Patel et al. 2021). However, there is very little data on more specific health disparities within the MENA population because of a lack of census data. Racialization is occurring, as evidenced by the extreme rise in Islamophobia during the Trump regime, due to Trump’s blatant anti-immigration rhetoric and policies targeting MENA populations. However, because of a lack of grouping by race, there is no way to address these inequalities. This leaves MENA people in a difficult–and ultimately invisible–position

Social Discrimination

MENA people are treated differently than White people by the U.S. population. A study from 2019 found that “…around 60% of Arabs in the United States reported workplace discrimination after 9/11, and 40% of Americans admitted to being prejudiced toward Arabs, Muslims, or both” (Abboud 2019). In places that do collect Census data on MENA people, it was found that “MENAs report rates of discrimination higher than Whites, and on par with other groups of color,” (Maghbouleh et al. 2019). However, we do not have current statistics on this in the United States. As a result of the diversity within MENA populations (11 ethnicities and 19 nationalities), it is difficult to measure to what extent these rates of discrimination vary among populations without more specific data, which would be most accessible through the Census.

In recent years, however, anti-MENA sentiment in the United States has been proliferating. Since the terror attacks in New York City on September 11, 2001, there has been a sharp rise in the perception of MENA people–especially those with Islamic beliefs–as terrorists. Additionally, during the Trump administration, several executive orders were passed that created migration restrictions specifically targeting MENA countries. This combination has created a “perfect storm” of anti-MENA sentiment over the past two decades, perpetuated predominantly through Islamophobia and stereotyping. These experiences have pushed many MENA people to begin identifying as non-White, second-generation (children of MENA immigrants) individuals in particular (Maghbouleh et al. 2019). However, without more specific Census data, it is impossible to collect more precise data on the types of discrimination that MENA populations in the United States may face.

Discrimination in Healthcare

A 2021 study on the social risk factors and their connections to health outcomes in MENA populations found that the MENA rate of fair or poor health status almost mirrors that of African American and Latino populations in several metropolitan areas around the United States. Additionally, many MENA people are at increased risk for food insecurity and financial strain (Patel et al. 2021). MENA people do not benefit from White privilege, as even with limited research, their health disparities are disproportionate to those of White populations. However, there is very little data on more specific health disparities within the MENA population because of a lack of census data.

One major consequence of this lack of census data is that MENA people cannot access healthcare services as easily as White people. While there are no government statistics on this, several studies have been done to provide further evidence for the need for MENA inclusion in the census. One such study (Harper 2022) investigated barriers to cancer screening in MENA populations. Several of these included:

- The language barrier

- A lack of information or knowledge on healthcare topics

- Healthcare accessibility

- Health providers being culturally insensitive

- Fears related to immigration or immigration status

As a direct result, MENA women in the U.S. have much lower estimates of cancer screenings and recommended vaccinations, including for the flu and pneumonia. Additionally, they had fewer Papanicolaou tests and breast examinations than US-born White women (Harper 2022). With accurate counting of MENA people on the Census, many of these issues could be officially recognized and somewhat addressed through MENA-specific healthcare programs.

Looking Ahead

In the wake of the recent rise in MENA hatred in the American public, many activists began advocating for MENA inclusion in the 2010 Census. As a result, the Census Bureau began a test in 2015 to investigate how MENA populations might respond to an additional category on the Census. However, several years later, in 2018, under the Trump administration, the Bureau “…rejected the recommendation to add a MENA category on the grounds that ‘more research and testing is needed,’” (Maghbouleh et al. 2019). Many activists were not satisfied with this response. The Bureau had already received data from their investigation in 2015, and protests from MENA populations had been increasing since before 2010, so this rejection seemed like a hollow excuse made by an administration that had already proven hostile to MENA people.

The struggles of MENA people in the U.S. have been unacknowledged for far too long, and if they continue to go ignored then this population will fall further into disparity while remaining unrecognized by the general public. Looking ahead, however, it seems as though efforts to include MENA people on the 2030 Census may be less futile. With the 2020 Census, as a result of social media, there was a large increase in the amount of public awareness on this issue, and a much larger outcry when the Bureau ultimately chose to continue excluding MENA people from the Census. This rallying of support for MENA representation gave many people hope for potential change in the future.

MENA Americans have not been treated as White, and while some may benefit from White privilege because of the lighter color of their skin, they still experience discrimination, hate, and disparity as a result of their race that White populations do not. They deserve to have their struggles recognized and to be counted separately on the Census.

References

Abboud, Sarah, Perla Chebli, and Em Rabelais. 2019. “The Contested Whiteness of Arab Identity in the United States: Implications for Health Disparities Research.” American Journal of Public Health 109(11):1580–83.

Awad, Germine H., Hanan Hashem, and Hien Nguyen. 2021. “Identity and Ethnic/Racial Self-Labeling among Americans of Arab or Middle Eastern and North African Descent.” Identity 21(2):115–30.

Harper, Diane M. et al. 2022. “Comparative Predictors for Cervical Cancer Screening in Southeast Michigan for Middle Eastern-North African (MENA), White and African American/Black Women.” Preventive Medicine 159:107054.

Jensen, Eric. 2022. “Measuring Racial and Ethnic Diversity for the 2020 Census.” The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 11, 2022 (https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2021/08/measuring-racial-ethnic-diversity-2020-census.html).

Maghbouleh, Neda, Ariela Schachter, and René D. Flores. 2022. “Middle Eastern and North African Americans May Not Be Perceived, nor Perceive Themselves, to Be White.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119(7).

Nick, I. M. 2013. “A Question of Faith: An Investigation of Suggested Racial Ethnonyms for Enumerating US American Residents of Muslim, Middle Eastern, and/or Arab Descent on the US Census.” Names 61(1):8–20.

Patel, Minal R. et al. 2021. “A Snapshot of Social Risk Factors and Associations with Health Outcomes in a Community Sample of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) People in the U.S.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 24(2):376–84.