“If you want to be successful here [in America], you gotta master English. It’s a must… Language is the key… I want my children to know Korean because that’s our heritage, but we are living in America and the language of America is English… I want them to do well in school and go to a prestigious college.”

(Choi 2015)

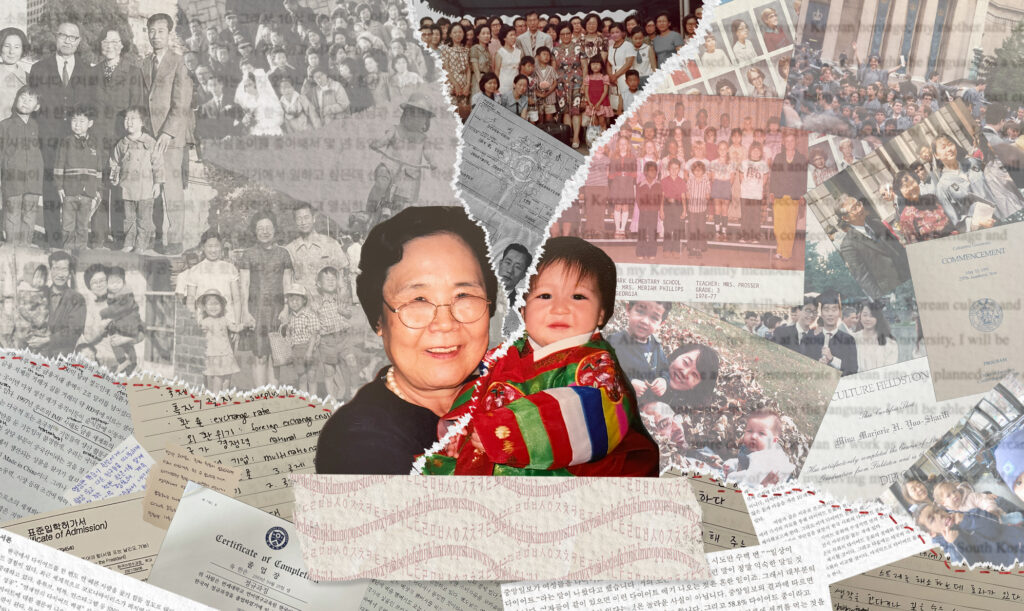

Immigrant parents often believe teaching their children English is a requirement for their success. However, in the process of learning English and assimilating to American culture, it is not uncommon for heritage languages to be lost across generations (Alba et al. 2002). From the moment children enter English-speaking schools, both their usage and proficiency in their heritage language tend to decrease. As they enter society and spend less time with their families, maintaining their heritage language becomes increasingly difficult (Kaveh and Sandoval 2020).

Heritage language loss is particularly severe in Asian Americans as compared to Hispanic groups. The physical distance of their countries of origin makes visits home difficult and maintaining the language even more so. Maintaining a heritage language only gets harder moving down the generations. By the third generation, English almost always takes over; for 90-95% of Asian immigrants, only English is spoken in the home (Alba et al. 2002).

Family Relationships

“I want to be able to communicate with my parents more. I usually speak to my parents with simple terms such as ‘I’m hungry’, ‘what is for dinner’, etc. I feel that I’ll have a better relationship with my parents if I at least converse with them.”

(Cho, Cho, and Tse 1997)

The loss of language does not come without a price. It often results in worsened family relationships as family members lose the ability to communicate. Even if simple control of the language is maintained, deeper connections are harder to form when family members cannot fully express themselves to each other.

Shared language erosion refers to the phenomenon when immigrant children quickly pick up English and lose heritage language proficiency, while parents maintain the heritage language and learn English at a much slower pace. This leaves the family without a shared proficient language. Conflict resolution is difficult and conversations are filled with misunderstandings. Additionally, parents struggle to pass on advice and guide their children through difficult situations (Cox et al. 2021). It is no surprise that a positive correlation is found between adolescents’ language proficiency and their relationship with their parents (Oh and Fuligni 2009).

Personal Identity

“When one of the most fundamental elements of a culture is language, what does it mean to not have that language?”

(Hsieh, Kim, and Protzal 2020)

Maintaining a sense of cultural and ethnic identity after immigration is difficult, and without one’s heritage language, it becomes even more so. A form of imposter syndrome can develop; one may feel like they do not deserve to identify with their culture because they lack the proper “qualifications” (Cho, Cho, and Tse 1997).

There are also many benefits to speaking one’s heritage language. Strong heritage language proficiency is correlated with self-confidence, stronger and more positive ethnic identity, and stronger connections with others in the community (Oh and Fuligni 2009, Brown 2009, Cho 2000).

Shame and Rejection

“Whenever I encountered Koreans, many of them looked down on me because I couldn’t speak Korean. Some are bold enough to scold me. Some blame me or my parents because I didn’t learn…Shame, embarrassment and anger.”

(Cho 2000)

While language is often a source of pride, the loss of it can result in feelings of shame or failure (Cho 2000). Beyond self-originating judgment, individuals who cannot speak their heritage language frequently face rejection or criticism from others in their communities because of this inability (Cho, Cho, and Tse 1997). Whether through light-hearted teasing or sharp criticism, these comments are frequent and can add to the individual’s sense of shame.

Language loss may also make it difficult to return to one’s family’s country of origin, where one may face rejection due to their inability to speak the language (Cho 2000). While one’s family’s country of origin often holds strong emotional ties, if the heritage language is lost, it can be difficult for second or third-generation immigrants to feel that connection. This disconnect from one’s cultural heritage only adds to feelings of isolation and shame.

Barriers

With so many consequences resulting from heritage language loss, why don’t more second or third-generation immigrants choose to study their heritage language? The answer is that it is often not as simple as enrolling in a course or downloading an app. First, if one’s heritage language is not commonly spoken, resources can be scarce. With just under half of the world’s languages facing extinction, many individuals are left without adequate resources to study their heritage language (Roche 2020).

Additionally, second and third-generation immigrants face unrealistic expectations of proficiency from both themselves and others, adding extra pressure to the learning process (Shimkus 2022). People feel more language anxiety towards languages they think they should know well (Dewaele, Petrides, and Furnham 2008). This makes it easy to lose confidence and, in turn, lose motivation to learn their heritage language (Cho, Cho, and Tse 1997).

So what can be done to combat this? A starting point is to change the way we think about language. American society still prioritizes perfect English skills, with those who lack them facing many barriers (Choi 2015). By accepting those with lower proficiency or accented English, we can decrease the pressure on immigrants to prioritize English at the cost of their heritage language. Another effort is to decrease the shame surrounding heritage language loss. The shame and stigma attached to language loss only make it harder for heritage language learners through the added stress and pressure. By acknowledging the complexities that immigrants face, we can lessen the judgment surrounding language loss. Further, placing value on multilingualism and intercultural competence will create a society that fosters language and cultural maintenance.

Sources

Alba, Richard, John Logan, Amy Lutz and Brian Stults. 2002. “Only English by the third generation? Loss and preservation of the mother tongue among the grandchildren of contemporary immigrants.” Demography 39(3):467-484.

Brown, Clara Lee. 2009. “Heritage Language and Ethnic Identity: A Case Study of Korean-American College Students.” International Journal of Multicultural Education 11(1). https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v11i1.157

Cho, Grace, Kyung-Sook Cho, and Lucy Tse. 1997. “Why ethnic minorities want to develop their heritage language: The case of Korean‐Americans.” Language Culture and Curriculum 10(2): 106-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908319709525244

Cho, Grace. 2000. “The Role of Heritage Language in Social Interactions and Relationships: Reflections from a Language Minority Group.” Bilingual Research Journal. 24(4):369-384.

Choi, Jinny K. 2015. “Identity and language: Korean speaking Korean, Korean-American speaking Korean and English?” Language and Intercultural Communication 15(2): 240-266,

Cox, Ronald B.,Jr., Darcey K. deSouza, Juan Bao, Hua Lin, Sumeyra Sahbaz, Kimberly A. Greder, Robert E. Larzelere, Isaac J. Washburn, Maritza Leon-Cartagena and Alma Arredondo-Lopez. 2021. “Shared Language Erosion: Rethinking Immigrant Family Communication and Impacts on Youth Development.” Children 2021 8:256. https:// doi.org/10.3390/children8040256

Dewale, Jean-Marc, K.V. Petrides, and Adrian Furnham. 2008. “Effects of Trait Emotional Intelligence and Sociobiographical Variables on Communicative Anxiety and Foreign Language Anxiety Among Adult Multilinguals: A Review and Empirical Investigation.” Language Learning 58(4): 911-960.

Hsieh, B., Kim, J., & Protzel, N. 2020. “Feeling Not Asian Enough: Issues of Heritage-Language Loss, Development, and Identity.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 63(5):573– 576. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1030

Kaveh Yalda M. and Jorge Sandoval. 2020. “ ‘No! I’m going to school, I need to speak English!’: Who makes family language policies?” Bilingual Research Journal 43(4):362-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2020.1825541

Lee, Hakyoon. 2021. ““No more Korean at Home.” Family language policies, language practices, and challenges in Korean immigrant families: Intragroup diversities and intergenerational impacts.” Linguistics and Education 63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2021.100929

Oh, J.S. and Fuligni, A.J. 2010. “The Role of Heritage Language Development in the Ethnic Identity and Family Relationships of Adolescents from Immigrant Backgrounds.” Social Development 19:202-220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00530.x

Roche, Gerald. 2020. “Abandoning endangered languages: Ethical loneliness, language oppression, and social justice.” American Anthropologist 122(1):164-169. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13372Shimkus, Anna. 2022. “Language Learning, language loss” The Whitman College Pioneer: Whitman College. advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:66R0-79D1-JBSN-351K-00000-00&context=1516831.