“Republicans are constantly fighting like a boxer with his hands tied behind his back…You will have an illegitimate president. That’s what you’ll have. And we can’t let that happen. These are the facts that you won’t hear from the fake news media. It’s all part of the suppression effort. They don’t want to talk about it.”

Donald Trump, January 6, 2021 (CNN, 2021)

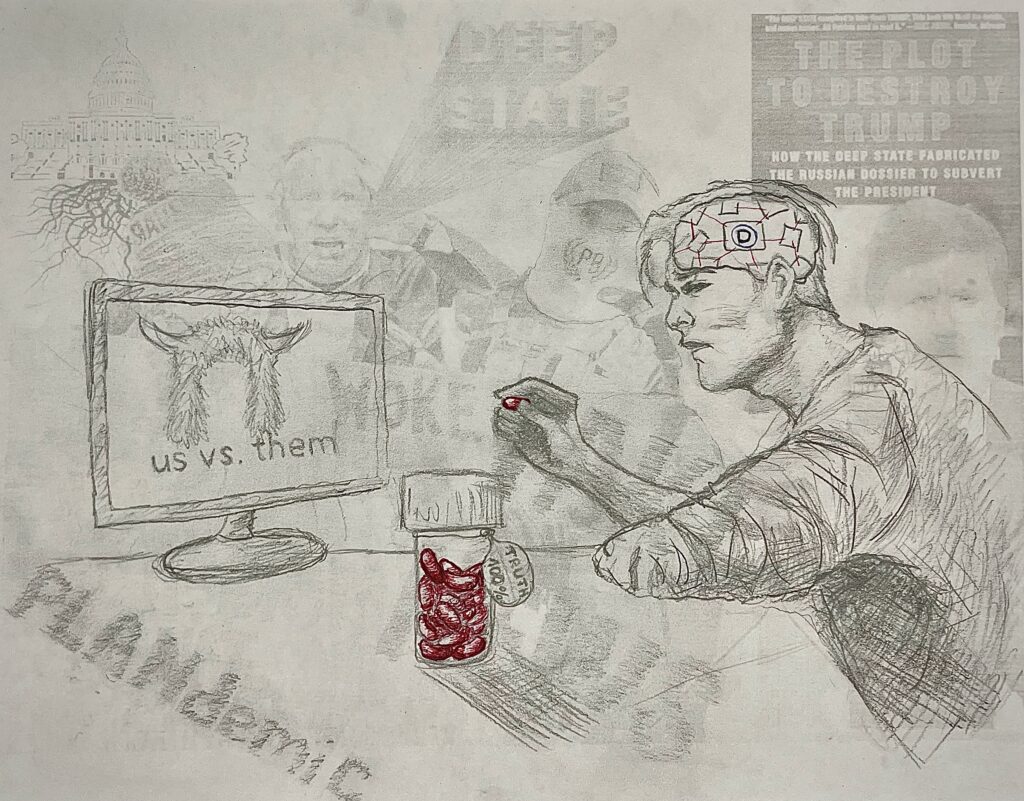

January 6, 2021 highlighted the deep political polarization in the United States, fueled by misinformation from the Right. Former President Trump refused to accept the results of the November 2020 presidential election, claiming without evidence that the vote had been rigged and stolen from him (Barry et al., 2021). Trump convinced hundreds of his supporters to believe in his conspiracy theory and protest as his last attempt to stay in power. Far-right extremists, such as the anti-government militia Oath Keepers, the neo-fascist organization Proud Boys, and radio show host Alex Jones, led the protest to “protect” democracy. How did Trump’s supporters come to believe in conservative conspiracy theories?

A conspiracy theory is an explanation of an event based on the idea of a secret plot by a perceived powerful or influential elite (Uscinski et al., 2016). Three main factors contribute to developing conspirative thinking: partisanship, feelings of crisis, and feelings of being underappreciated in society (Douglas et al., 2019). Members of the conservative elite, such as media figures and politicians, can convince their partisan supporters of those factors by manipulating media algorithms and creating informational echo chambers. The constant exposure to the “us vs. them” ideas often victimize the white male conservative viewers, causing them to seek the “truth” in the promoted conspiracy theories. Republicans who believe in conspiracy theories suggest that Democrats are taking away their government and threatening their conservative values through stolen elections, inclusive education of children, and gun control (Bolla Tripodi, 2022, p. 37, 131).

Partisan Roots

Partisans tend to believe theories that support their party and attack the opposition. It is important to note that such bias can be present on both sides, especially on the extremes. However, conspiracy theories are more prevalent among Republicans than Democrats (Uscinski et al., 2016). The conservative elite encourages doing research on the internet and distrusting rival media. They know how to manipulate search engine algorithms through keywords to guide their supporters into a rabbit hole of conservative media, much of which holds conspirative logic (Bolla Tripodi, 2022).

Conservative Political Media Alliance Promoting Misinformation

Extremist groups, such as QAnon, propose and support conspiracy theories that gain a following when popular outlets promote them. Conservative media like Fox News and personalities like Alex Jones on InfoWars feature and amplify their conspirative ideas. They make them popular enough to reach politicians who would use those conspiracy theories for political gains or to distract from wrongdoings (Bolla Tripodi, 2022; Mason, 2016). Politicians can also collaborate with extremists to create or popularize conspiracy theories, such as how Trump claimed the 2020 presidential election was a fraud because he lost (Barry, 2021).

Once politicians and the media start mentioning conspiracy theories, the stories become popular enough to reach people outside the extremist circle. But that does not mean those people will immediately believe them.

The viewers must be convinced of the threats extremists believe, which happens on the web through what sociologist Bolla Tripodi explains as algorithmic manipulation (2022, p. 19). Conservative elites spread doubt regarding popular mainstream media and instead encourage searching for the truth online. Their supporters are more likely to trust what they find themselves and what confirms their personal beliefs. Keywords such as “red pill” and “woke” can spark curiosity in individuals who will look them up online (Bolla Tripodi, 2022, p. 141). Those phrases guide the web search because they are part of a repeated extremist dialect used in mainstream media. Then, the algorithm recognizes the interest in the ideas expressed by those keywords and starts suggesting more conservative media. One curious web search can be the start of an algorithmic rabbit hole. Yet, exposure alone is not enough to believe in conspiracy theories (Uscinski et al., 2016).

Conservative Values Under Threat → Feelings of Crisis

Online white conservatives tend to think liberals are attacking their conservative values of: “faith, family, firearms, the armed forces, and a free market” (Bolla Tripodi, 2022). These values are the foundation of the conservatives’ political, social, and cultural collective identity online. Some online communities and forums cater specifically to conservatives, where they can discuss their beliefs and share news articles and other information that aligns with their views. When values are threatened, so are the community’s identity, leading to crisis feelings (Mason, 2016). In his speech on January 6, Trump claimed the media and the elections were not “free,” which signaled a direct threat to conservative values and the community (CNN, 2021; Mason, 2016). The threat led to a feeling of crisis, urging Trump supporters to react.

Alienation/Loss of Power in Society → Feelings of Being Underappreciated

Online white conservatives see government support towards minorities as threatening, which makes them feel underappreciated (Bolla Tripodi, 2022; Mason, 2016). White male conservatives do not face oppression like other groups in the US. However, they can still feel alienated or rejected when they feel replaced by minorities (Bolla Tripodi, 2022; Mason, 2016). Conspiracy theories can serve as an alternative narrative, which would victimize them and align more with their conservative values.

Feelings of crisis and being underappreciated fuel the “us vs. them” mentality, causing extremist groups to create these stories and partisans to believe them.

Summary: Process of Conspirative Socialization

Why do individuals come to believe those ideas?

- Informational echo chambers created by the algorithm reaffirm conspirative logic through constant exposure to those ideas, which amplifies feelings of crisis.

- The individuals might relate to those conspiracy theories because they hold the same conservative values.

- Feeling undervalued, alienated, or replaced in society can result in a crisis feeling. Those people seek an explanation for their situation, which results in acquiring a conspiratorial imagination.

In conclusion, January 6 was a stark reminder of the dangers of conspiracy theories in political discourse. Once we understand the different societal, historical, and political factors that can drive people to believe in conspiracy theories, we can find a solution to misinformation.

Work Cited

Andrade, G. (2020). Medical Conspiracy Theories: Cognitive Science and Implications for Ethics. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 23(3), 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-020-09951-6

Barry, D., McIntire, M., & Rosenberg, M. (2021, January 9). ‘Our President Wants Us Here’: The Mob that Stormed the Capitol. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/09/us/capitol-rioters.html

CNN. (2021, February 8). Read: Former President Donald Trump’s January 6 Speech | CNN Politics. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/02/08/politics/trump-january-6-speech-transcript/index.html.

Douglas, K. M., Uscinski, J. E., Sutton, R. M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C. S., & Deravi, F. (2019). Understanding Conspiracy Theories. Political Psychology, 40(S1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568

Mason, L. (2016). A Cross-Cutting Calm: How Social Sorting Drives Affective Polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw001

Tripodi, F. B. (2022). The Propagandists’ Playbook: How Conservative Elites Manipulate Search and Threaten Democracy. Yale University Press.

Tucker: We heard you. It’s hard to trust anything. Here’s what we know. (2020, November 9). In Tucker

Carlson Tonight. Fox News. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R5ki6S-WsKU

Uscinski, J. E., Klofstad, C., & Atkinson, M. D. (2016). What Drives Conspiratorial Beliefs? The Role of Informational Cues and Predispositions. Political Research Quarterly, 69(1), 57–71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44018529

Image References:

Becker1999. (2020). Free Ohio Now. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/becker271/49876163551/.

Holt, Jared. (2018). Alex Jones DC Press Conference 2018. Photo. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alex_Jones_DC_Press_Conference_2018.jpg.

Livingston, Geoff. (2020). Proud Boys Confrontation. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/geoliv/50950060227.

OpenClipart. (2020). Deep State. Sketch. https://freesvg.org/1534704850.

OpenClipart. (2020). Deep State Typography 3. Typography. https://freesvg.org/1534704992.

Skidmore, Gage. (2016). Donald Trump. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/25218642186/.

Steam Pipe Trunk Distribution Venue. (2019). Matt Gaetz on Tucker Carlson on Fox News. Photo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/waffleboy/50230394886.