I scroll myself into a deep hole as the clock strikes midnight. My thumb is robotic, swipe, flick, swipe, as I mindlessly scroll through my Tik Tok feed. Once again, I have fallen into the trap of the endless scroll.

While scrolling, I encounter countless influencers who seemingly have the “perfect body.” I feel my self-confidence plummet. I notice the videos and pictures with the most likes are the ones that have girls revealing the most. This trend has become a pervasive influence in the lives of teenage girls, affecting their body image and self-worth. This culture of likes coupled with unattainable beauty standards results in girls feeling pressure to grow up quicker (Lopez, 2021; Van Oosten, 2010; Baumgartner, 2015).

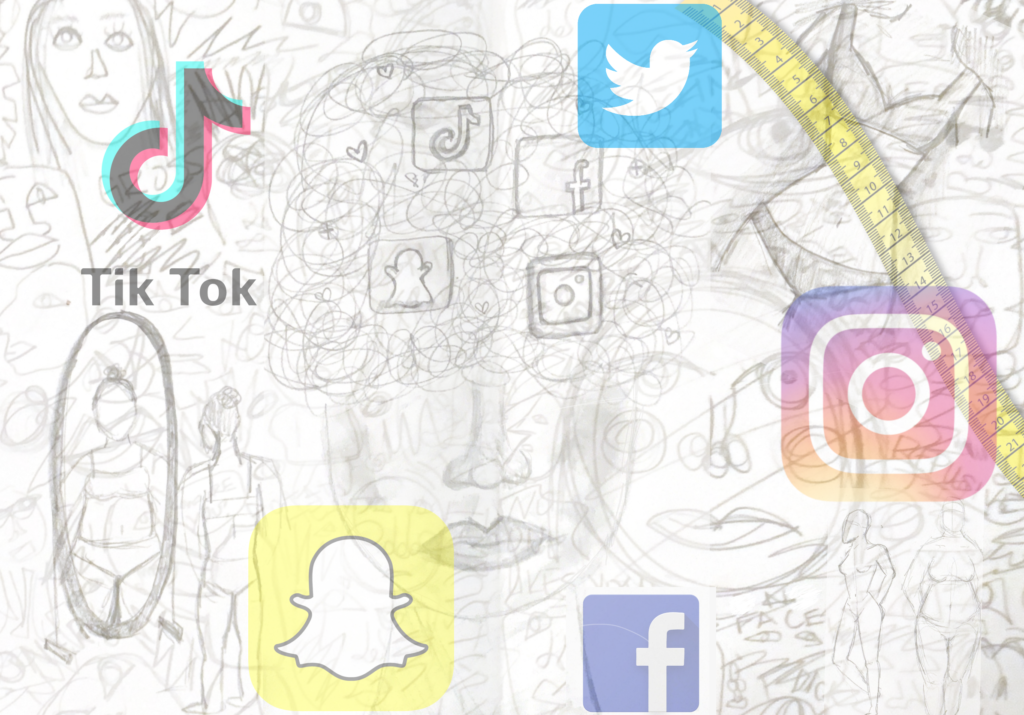

In the past decade, social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, Youtube, Tik Tok, and Facebook have grown in popularity. Approximately one third of teenagers claim they are on one of these platforms constantly (Atske, 2022). While these social media platforms allow people to connect with friends and family, they also are highly unregulated. Oftentimes because these platforms are easily accessible and made for older age groups they can expose young girls to too much too soon (Van Oosten, 2010).

The Kardashian Effect

The Kardashians popularized the idea of social media influencers through their unattainable beauty since they rose to fame in 2007. The Kardashians are just one example of influencers, as the broad scope of influencers has continued to grow. The Kardashians are notably some of the most successful influencers, as they have a combined net worth of over 2 billion (McClain, 2015). They also are some of the most liked and followed influencers. Kylie Jenner, Kim Kardashian, and Khloe Kardasihan all have over 300 million instagram followers making them some of the most followed people on instagram.

The Kardashians have all had plastic surgery and other procedures to enhance their appearance. They have denied having any work done in the past, but most have eventually admitted it. This denial of plastic surgery creates unattainable beauty standards. For example, a trend started in 2015 called the “Kylie Jenner lip challenge” where people would film themselves putting a shot glass or bottle around their lips and then sucking the air out. Causing their lips to get puffy with the goal of doing this being to look like Kyle Jenner. This trend was sometimes harmful causing excessive swelling and bruising. Also if the shot glass is glass, the friction can cause it to break causing further injury (Moyer, 2015). This is one example of how these unattainable beauty standards, such as big lips, can lead young girls to believe they should look like this to be considered beautiful (McClain, 2015).

A Filtered Reality

Unachievable beauty standards can also lead to the increase in social media users utilizing filters. These filters can smooth skin, blur pores, add makeup, and even change face shape completely. Six hundred million Instagram and Facebook users use filters monthly, and 76% of Snapchat users use them daily (Bhatt, 2020). A recent phenomenon related to this is “selfie dysmorphia,” where consumers experience body dysmorphia and negative self-esteem issues after visually enhancing selfies through filters or editing. If you constantly see yourself through filters and editing, it can be hard to recognize yourself without those filters. This can be highly damaging to young and adolescent girls who are still developing. When filters alter self-perception, it can lead them to feel less than or not as attractive without these filters (Javornik et al., 2022).

Culture Created by Social Media

Media and advertisements have oversexualized women for decades. The “ideal body” shown in these advertisements causes lower confidence in the women viewing these ads (Kilbourne, 2010; Ward, 2016). Social media operates similarly to this as it can lower confidence and create body image issues. However, it is even more extensive, as likes and followers add a new layer to this problem. Social media fosters a culture where likes, comments, and how many followers one has influences self-worth. The interactions that take place on social media platforms are based on socially evaluative contexts (Lopez, 2021). These “evaluations” happen anytime someone engages in posting on a social media platform. In these interactions, people make quick judgments about someone’s life while only having a small piece of one’s actual story. The fear of negative evaluations in these interactions leads to girls having anxiety and desiring positive evaluations in order to be liked and accepted (Lopez, 2021).

Effects on Young Girl’s Body Image

Following the concept of socially evaluative situations that happen on social media, girls in high school and younger feel these effects and think they must show more skin to be popular. More prominent online creators set this example; then it trickles down to make a mark on the younger girls looking up to these influencers (Daniels, 2016). These young girls look up to these influencers. Therefore, when these creators post more scantily clad photos of themselves, they often get lots of likes and comments (Daniels, 2016). This creates norms for younger girls that can make them feel inclined to post themselves sexually online to be more popular (Baumgartner, 2015). They may present themselves in sexually suggestive poses or clothing (ex, bathing suits or underwear)(Van Oosten, 2010). Adding onto that, “this overabundance in the exposure of sexualized media fosters the internalization of sexual objectification” (Mull 2020). The more frequently adolescent girls engage in this behavior, the more it is seen as a crucial part of their self-worth.

Solutions

There are many ways to minimize social media’s harmful effects. One way is not to allow young kids on social media. Parents can monitor their children’s accounts or not allow them to be on social media at a young age. Also, Platforms can monitor this by having age limits. Currently most platforms do have age limits, for example having to be 13 in order to be on Snapchat. However, most of these age limits are not heavily monitored and can be easily bypassed by giving a false birthdate. So if they were more strictly enforced, it would help to keep young children from feeling these effects of social media.

While these help on an individual level, it does not tackle the bigger problem of the toxic culture created by social media. If young girls see popular influencers for being funny, creative, or smart it shows that you do not have to show more skin to get more likes, it helps change the narrative. Some examples of strong female role models focused on breaking down the toxic culture created by social media include Selena Gomez, Lizzo, and Simone Biles to name a few. Also, when popular creators use fewer filters and show flaws, it shows that it is ok to be imperfect and that these ideals are unattainable. Society will have to continue adapting to these challenges created by social media as its influence grows.

Bibliography

Bhatt, Stephali. 2020. “The Big Picture in the Entire AR-Filter Craze .” The Economic Times. Retrieved May 1, 2023 (https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/brands-see-the-big-picture-in-augmented-reality-filter-craze/articleshow/78266725.cms).

Baumgartner, Susanne, Sindy R. Sumter, Jochen Peter, Patti M. Valkenburg, 2015. Sexual self-presentation on social network sites: Who does it and how is it perceived? Computers in Human Behavior. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563215002599?via%3Dihub#b0270

Daniels Elizabeth A., Eileen L. Zurbriggen, 2016. “It’s not the right way to do stuff on Facebook:” an investigation of adolescent girls’ and young women’s attitudes toward sexualized photos on social media. Sex Cult; 1–29 Google Scholar

Javornik, Ana et al. 2022. “‘What Lies behind the Filter?’ Uncovering the Motivations for Using Augmented Reality (AR) Face Filters on Social Media and Their Effect on Well-Being.” Computers in Human Behavior 128.

Kilbourne, Jeanne. Media Education Foundation.2010. Killing us softly: Advertising’s image of women. Killing Us Softly. Retrieved November 2022 (https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/216732.)

Klettke, Bianca. Hallford, David J, Mellor David J. 2014. Sexting prevalence and correlates: a systematic literature review. Clin Psychological Review; 34:44–53 Crossref, Google Scholar

Lopez, Richard., & Polletta, Isabel. 2021. Regulating Self-Image on Instagram: Links Between Social Anxiety, Instagram Contingent Self-Worth, and Content Control Behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.711447

Mcclain, Amanda Scheiner. 2015. Keeping up the Kardashian Brand: Celebrity, Materialism, and Sexuality. New York, NY: Lexington Books.

Moyer, Justin. 2015. “Kylie Jenner Lip Challenge: The Dangers of ‘Plumping That Pout’.” The Washington Post. Retrieved May 1, 2023 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/04/21/kylie-jenner-challenge-the-dangers-of-plumping-that-pout/).

Mull, Keira. 2020. Effects of Sexual Objectification of Women in the Media . Illuminate Journal. Retrieved April 17, 2023 (https://www.illuminatenrhc.com/post/effects-of-sexual-objectification-of-women-in-the-media-by-keira-mull)

Ng, Stephanie. 2017. Social Media and the Sexualization of Adolescent Girls. Psychiatry Online. Retrieved February 20, 2023 (https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2016.111206)

Van Oosten Johanna M, Peter Jochen, Inge Boot. 2014. Exploring associations between exposure to sexy online self-presentations and adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10.1007/s10964-014-0194-8

Atske, Sara. 2022. “Teens, Social Media and Technology 2022.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved April 18, 2023 (https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/).

Ward, Monique L. 2016. Media and sexualization: State of empirical research, 1995-2015. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4-5), 560-577. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1142496