As a woman of color, I was constantly told by my mother when I was just a little kid that being White is what would make me beautiful. I remember days when she would tell me to marry a White guy when I was older so that our children could have long, silky beautiful hair. What I thought was a simple mother-daughter inside joke turned out to unleash many insecurities about my appearance. I was taught by her to hate my coarse, coily hair because it’s “high maintenance.” As she would comb through my hair— all I can remember is her words saying “I wish you would have been born with straight hair.” Those few little words did nothing but fuel an internal hatred for my external appearance.

Sadly, instances like my own are far from an aberration. Today, the White capitalist society continues to show that it is willing to profit from internalized White supremacy even though it may be harmful. They do this by bombarding women of color with cosmetic advertisements, famous influencers, and the idea that we will be an outcast if we don’t conform to such standards.

Skin Lightening

The desire for lighter skin is not a new phenomenon. It has been prevalent for centuries in Asia, the Caribbean, and South America. Yet, Black consumers are using skin bleaching products and pigment removal creams now more than ever before. Today, around 77% of Nigerians, 35% of South African, and 70% of Jordanian women say they practice skin bleaching. In 2020, the skin lightening industry was valued at 8.6 billion US dollars and is expected to increase to 12.3 billion by 2027 (Hall, 2021).

Where exactly did this idea of being lighter is “better” come from?

Skin lightening has long been associated with deeply rooted racism plus beauty standards suggesting that appearing ‘White’ is what makes you beautiful. White colonists used to associate blackness with harmful meanings of “primitiveness, lack of civilization, unrestrained sexuality, pollution, and dirt” (Glenn, 2008).

These negative connotations towards blackness have lingered over time. A 1930 French advertisement for Dirtoff depicts a dark-skinned man washing his hands with soap to become more White, which presumably is what their audience wants. Even images showing Black people “dramatically losing their pigmentation as a result of the cleansing process” were common in a lot of historical soap advertisements, according to French art historian Jean Messing (2012). This in turn would influence and pressure a lot of people of color to do everything in their power to appear less dark because it is “bad,” and you will be looked down upon.

However, this notion still affects many women of color today. A professor at the University of West Indies, Christopher Charles, concluded in his 2012 research that those who did bleach their skin did not bleach it out of self-hate, but because they were pursuing conceptions of fashion and beauty defined by European standards. Charles argued that those who bleached their skin were simply miseducated to internalize a concept of beauty based on European ideals.

The issue is that White society pushes whiteness as attractive and superior. This ideology is making women of color start to hate themselves and feel like they have to comply with these European standards so that they are not being outcast in society. This idea is explained through the “White supremacy ideology,” where the institution of slavery was justified by a belief system that marked whiteness as superior to all (Hill, 2002). Because ‘whiteness’ is emphasized as being a superior skin tone, this ideology could encourage dangerous standards. This notion can cause people to believe that if they are not White, then they are inferior to those who are White.

Brazilian Butt Lift

Brazilian Butt Lifts (BBL) are also starting to target women of color as well. This is partly due to White stereotypes of what women of color are supposed to look like. While famous influencers such as Nicki Minaj, Cardi B, and Kim Kardashian flaunt their expensive BBL to their young fans for fame, they don’t don’t mention to those same fans that BBLs may not be as desirable as what is portrayed. The dark deep truth behind the BBL is that it not only degrades women of color, but has long served as part of white mens’ fantasies about women of color (Gaines, 2017).

The fetishization of a Black woman’s bottom extends back to the case of Saartjie Baartman, a South African woman who was brought back to London in 1810 by a British doctor. She was used as an exhibition where crowds would pay to examine her body, and her buttocks in particular (Gaines, 2017).

So as women of color, why do we subject ourselves to the fantasies and fetishizations by the White man?

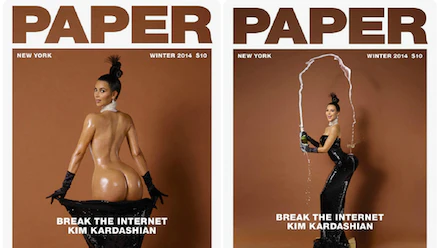

Similar cases are even prevalent today. Kim Kardashian, for example, posed for Paper magazine in 2014 with a champagne glass balanced on her bottom, which can be compared to the pictures that Baartman used to advertise her exhibits. This occurrence stems from colonial culture and how it has become more fascinated with derrières. People focus on sculpting the butt in a bubble-like curvature because of the symbolic value that it holds of fertility. When aesthetic surgery is performed on the buttocks it is to enhance their sexual attraction, and increase a man’s desire to reproduce with a woman (Barrera, 2002). The idea that Black women are encouraged to complete deadly procedures to have a big and curvy butt to be considered attractive encourages unhealthy beauty standards. A 2017 study published in the Aesthetic Surgery Journal found that two out of 6,000 BBLs resulted in death making it the deadliest cosmetic procedure in the world. The way how the colonial White society objectifies a Black woman’s body and encourages her to risk her life just to cater to the White man’s gaze says a lot about how far they are willing to go to target and profit off of women of color.

Hair Straightening

Black women began their straightening of coarse textured hair in response to colonial beauty standards characterizing Black hair as “unruly.” Since the 1890s, many women have put relaxing chemicals in their hair, weaves, or damaging levels of heat in order to achieve a straight, silky look. The reason why women go for straight hair is explained through the deeply rooted hatred for coarse, coily hair. During slavery, White men depicted their actual hair as hair, but judged Africans’ hair as “wool”. As a result of this mentality, slaves were required to wear rags on their head to cover up their “undone” hair or iron their hair to appear acceptable and avoid offending White people (Hagro, 2011). Throughout the enslavement of Africans, light-skinned, straight-haired slaves were priced higher than dark-skinned, curly-haired ones (Thompson, 2009).

The differential treatment based on hair texture has led Black women to internalize that their kinky hair is unattractive or unprofessional compared to straight hair. Moreover, in the workplace, employers continue to enact microaggressions towards textured hair. For example, in 2010, Chastity Jones received a job offer as a customer service representative for a catastrophe management center. As a caveat for the offer, she was also requested to cut off her locs because they “tend to get messy.” When she had refused to do so, she lost the job offer (Griffin, 2019). Many women of color report similar accounts of discrimination due to their hair. A C.R.O.W.N research study conducted a study to understand how societal norms affect Black women in the workplace. The survey concluded that Black women were 1.5 times more likely to have reported having been sent home or know of a Black woman sent home from the workplace because of her hair (CROWN, 2019).

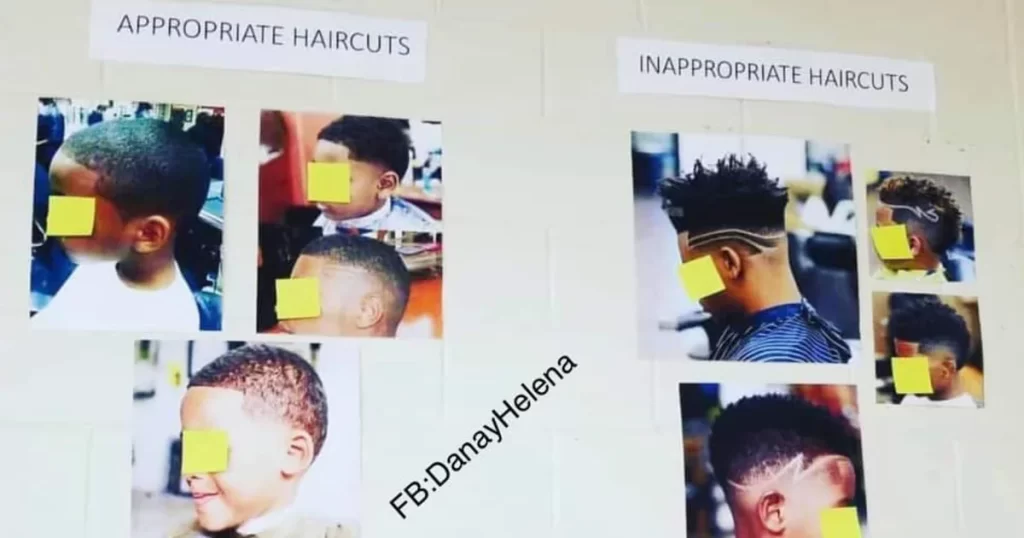

Furthermore, Black kids’ hair is similarly regulated by White school administrations. In August 2019, a Georgia elementary school posted a display of appropriate and inappropriate hairstyles for the students. Using Black children in the slides, the only hairstyles deemed appropriate were short, low cut styles for boys. There were no appropriate styles for girls. However, on the list of inappropriate hairstyles were high-tops, box braids, locs, and twists which are often hair styles that women of color use (Vigdor, 2019).

White societies reputation of textured hair continues colonial racism demeaning Black women. Why is it that locs are considered to be “messy,” but a person who comes to work in a messy bun isn’t? What is it about textured hair that is messy, and why do we equate texture with our professionalism? Just because my hair is in locs does not mean that I am any less of an employee, or just because my hair is in braids does not mean that I am a terrible student. We have to stop attributing appearance to our character traits because if we don’t, it will only continue to enforce racism within the beauty industry.

I hope we learn to one day find beauty in ourselves and be proud of our blackness. We are powerful and so is our beauty. However, it first starts with accepting that, and making it known that no matter our complexion, body shape, or hair texture, we are still confident and proud of who we are as Black queens. That morale is something that we should never lose sight of.

“I’m an Exquisite Black Queen! I like, love, and celebrate myself. I don’t fit society’s beauty standards, but I’m beautiful to me. I know my worth and I respect who I am as a woman. I’ve got beauty on the inside and that makes me empowered and powerful. I’m fearless and comfortable in my own skin. I’ve got flaws, but I’m still confident! This Queen right here is flawed yet phenomenal, valuable and unique!”

–Stephanie Lahart

Acknowledgment:

I would like to thank Kahleel Bernard ‘23, a current senior at Hamilton College, for her assistance on this project.

References:

Brown-Glaude, W. (2013). Don’t Hate Me ’Cause I’m Pretty: Race, Gender and The Bleached Body in Jamaica. Social and Economic Studies, 62(1/2), 53–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24384496

Crown Coalition. (2019, May 1). New Dove Study Confirms Workplace Bias Against Hairstyles Impacts Black Women’s Ability To Celebrate Their Natural Beauty. PR Newswire. Retrieved April 16, 2023, from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-dove-study-confirms-workplace-bias-against-hairstyles-impacts-black-womens-ability-to-celebrate-their-natural-beauty-300842006.html

Gaines, A. (2017). Black for a Day: White Fantasies of Race and Empathy. University of North Carolina Press.

GLENN, E. N. (2008). YEARNING FOR LIGHTNESS: Transnational Circuits in the Marketing and Consumption of Skin Lighteners. Gender and Society, 22(3), 281–302.

Hall, R. (2021, February 19). Women of color spend more than $8 billion on bleaching creams worldwide every year. The Conversation. Retrieved April 11, 2023, from https://theconversation.com/women-of-color-spend-more-than-8-billion-on-bleaching-creams-worldwide-every-year-153178

Hargro, B. (2011). Hair Matters: African American women and the natural hair aesthetic. (Master’s thesis) Georgia State University. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses

Hill, M.E. (2002). Skin color and the perceptions of attractiveness among African Americans: Does gender make a difference?” Social Psychology Quarterly, 65(1):77-91. http://www.jstor.org/stable /pdfplus/3090169.pdf?&acceptTC=true&jpdConfirm=true

Magdalena Barrera, “Hottentot 2000,” in Sexualities on History, eds. Kim M. Philips and Barry Reay (New York: Routledge, 2002), 407–16.

Rice, D., & Galbraith, M. (2008, November 16). How Natural Black Hair At Work Became A Civil Rights Issue. Retrieved April 11, 2023, from https://daily.jstor.org/how-natural-black-hair-at-work-became-a-civil-rights-issue/

Silva, D. F. (2022, August 1). Perspective | The hidden anti-Black history of Brazilian butt lifts. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 16, 2023, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/made-by-history/2022/08/01/hidden-anti-black-history-brazilian-butt-lifts/

Young, J. (1997). The Re-Objectification and Re-Commodification of Saartjie Baartman in Suzan-Lori Parks’s Venus. African American Review, 31(4), 699–708.