Television distorts, mocks and marginalizes fat people. Fat characters are reduced to caricatures whose stories and identities aren’t developed and don’t matter. TV audiences look down on fat characters because they are made fun of on the shows they are shown in (Himes 2007:713).

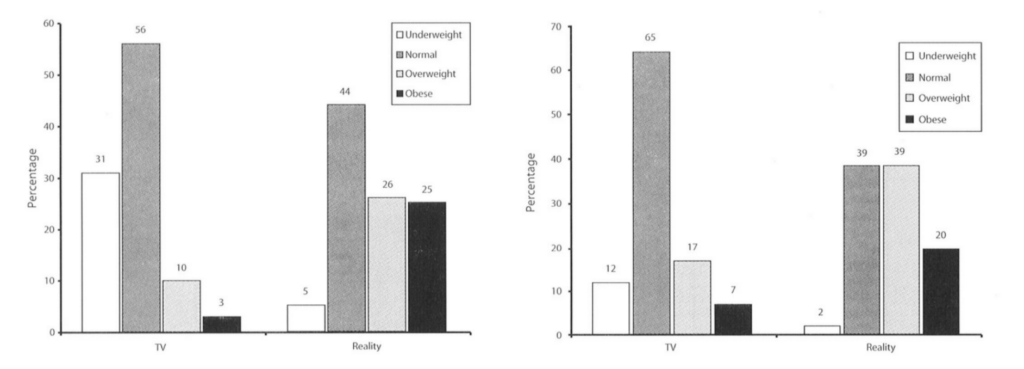

Not only is the representation of fat people overwhelmingly negative, but fat bodies are underrepresented on TV shows.

Figure 2: Comparison of male body types: television vs reality 1999-2000 (right)

(Brownell et al. 2003)

Fat people on TV are not complimented. In one study, all 36 compliments about appearance given to women were for thin women. Not one positive message was included for a woman of an average or overweight body type. For men, the same pattern was found: only one overweight character received a positive message (Tzoutzou et al. 2021:82).

These TV shows tell the audience that external beauty only resides in thinness and excludes anyone who deviates from this definition of beauty. Viewers can internalize this thin ideal, which in turn can make it difficult for the audience to feel good about themselves, especially if their body doesn’t fit this body standard (Himes 2007:716). Seeing how fat people are spoken about and treated on TV shows can affect how viewers think about their own bodies. This is especially true if their body type doesn’t fit the thin ideal emphasized on TV shows (Fouts et al. 1999:474).

Bigger Bodies, Smaller Roles

This pattern of dehumanizing fat people continues when they don’t get the chance to develop their characters. They are often represented as a villain or comedy sidekick. We don’t laugh with fat women, but at them (Bednarz 2020:7). Overweight women are about twice as likely to be the reason for a joke than thinner women (Brownell et al. 2003:1345). They also have smaller roles, less romantic relationships, and are in “fewer positive interactions than thin characters” (Himes 2007:713). Fat characters become less human than other characters who have full stories built around them.

Negative stereotypes often represent fat characters as villains. One study “found that obesity was equated with negative traits (evil, unattractive, unfriendly, cruel) in 64% of the most popular children’s videos” (Himes 2007:713). Examples of this can be seen in famous children’s movies with characters such as Ursula from The Little Mermaid or The Queen of Hearts from Alice In Wonderland. These villains help to draw the connecting line between fat and negative qualities. Not only are these characters characterized as ugly and contrasted with the ideal body type, but their personality is represented as ugly too. Makers of TV don’t just ignore fatness, they demonize it.

How These Representations Affect the Audience

The negative portrayal of fat people in TV shows can lead audiences to internalize negative portrayals of being overweight. This internalization can happen quickly: only 30 minutes of watching TV can affect how a young woman views her body which can result in various external struggles (Fouts et al. 1999:474).

In one study, girls agreed that the media influenced their desire to be thin and fit the beauty standard. This can cause frequent dieting (Tzoutzou et al. 2021:84) because many eating problems are due to unrealistic body standards, an image that mass media often transmits (Himes 2007:716).

Not only can these misrepresentations of fat people lead to low self esteem, but it can lead viewers to believe that they will be treated in the sexist ways that they see on TV if they don’t fit the body norm to avoid this. (Fouts et al. 2000:929-930).

“If one fails to match the ‘thin ideal,’ one may be subjected to sarcasm, derision, ridicule, and ‘helpful’ suggestions to lose weight or how to dress to hide a ‘weight problem’”

Fouts et al. 2000:929-930

All of these aspects have the potential to make a female viewer feel worse about themselves through their appearance and perceived reactions from other people rooted in fictional and distorted depictions on TV (Fouts et al. 2000:-930).

TV Should be Fun

TV is a space that is meant to be enjoyed. But viewers can’t sit back and relax with TV if they feel like their body is being judged by the shows that they put on. All bodies should feel like they have a space within TV shows. All bodies deserve to be seen by a wide audience.

Works Cited

American Profile. (2007, April 15). Kim Possible’ Voice. American Profile. Retrieved April 26,

2023, from https://americanprofile.com/articles/kim-possible-disney-voice/

Bednarz, Catherine. 2020. ““The Melissa McCarthy Effect”: Feminism, Body Representation and

Women-Centered Comedies.” Order No. 28767282 dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, United States — Pennsylvania (https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/melissa-mccarthy-effect-feminism-body/docview/2568246573/se-2).

Brownell, Kelly D., Matthew Eastin, Bradley S. Greenberg, Linda Hofschire and Ken Lachlan.

2003. “Portrayals of Overweight and Obese Individuals on Commercial Television.” American Journal of Public Health 93(8):1342-1348 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/portrayals-overweight-obese-individuals-on/docview/57062855/se-2).

Disney Castle Backgrounds: Disney Desktop Wallpaper, Disney background, Disney Castle.

Pinterest. (2018, May 7). Retrieved April 26, 2023, from https://www.pinterest.com/pin/691372980270302534/

Elastigirl. The Incredibles Wiki. (n.d.). Retrieved April 26, 2023, from

https://the-incredibles.fandom.com/wiki/Elastigirl

Fouts, Gregory, and Kimberley Burggraf. 1999. “Television Situation Comedies: Female Body

Images and Verbal Reinforcements.” Sex Roles 40(5-6):473-481 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/television-situation-comedies-female-body-images/docview/60077606/se-2).

Fouts, Gregory, and Kimberley Burggraf. 2000. “Television Situation Comedies: Female Weight, Male Negative Comments, and Audience Reactions.” Sex Roles: A Journal of Research

42(9):925-932 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/television-situation-comedies-female-weight-male/docview/57519856/se-2).

Himes, Susan M., and J. K. Thompson. 2007. “Fat Stigmatization in Television shows and

Movies: A Content Analysis.” Obesity 15(3):712-718 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/fat-stigmatization-television-shows-movies/docview/47597729/se-2). doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.635.

Kingdom Hearts Wiki. (2023, April 12). Rapunzel. Kingdom Hearts Wiki. Retrieved April 26,

2023, from https://www.khwiki.com/Rapunzel

McGrotty, A. (2022, April 19). Best barbie animated movies of all Time, ranked. MovieWeb.

Retrieved April 26, 2023, from https://movieweb.com/barbie-animated-movies/#barbie-in-a-mermaid-tale

Pin on Amo. Pinterest. (2019, June 17). Retrieved April 26, 2023, from https://www.pinterest.com/pin/619526492471601120/

Skinner, K. (2023, April 20). The top 10 Disney Princesses . Reel Rundown. Retrieved April 27,

2023, from https://reelrundown.com/animation/The-Top-Ten-Disney-Princess-Movies

Tzoutzou, Milia, Eirini Bathrellou and Antonia-Leda Matalas. 2021. “Cartoon Characters in

Children’s Series: Gender Disparities in Body Weight and Food Consumption.” Sexes 2(1):79 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/cartoon-characters-children-s-series-gender/docview/2656394509/se-2). doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2010007

Vanessa Doofenshmirtz. Heroes Wiki. (n.d.). Retrieved April 26, 2023, from https://hero.fandom.com/wiki/Vanessa_Doofenshmirtz

Wonder woman – justice league – render by moresense on deviantart. by Moresense on

DeviantArt. (n.d.). Retrieved April 26, 2023, from https://www.deviantart.com/moresense/art/Wonder-Woman-Justice-League-Render-899072146