“Girls are expected to work under a man”

In South Korea, my grandpa’s job in a restaurant was seen as more important in the eyes of the public than my grandma working in a beauty supply store. In keeping with Korean patriarchal culture, my grandparents encouraged me to choose a job where I can still support my family. Growing up, my Korean relatives reminded me that a girl like me should work under a man because that is what is expected. Meanwhile, they would tell my brother to get a top job in a business. This is because, in Korean culture, men are seen as assertive and dominant, whereas women are supposed to be nurturing and emotional–characteristics not associated with leadership.

Men can have it all, while women face oppression in the workplace

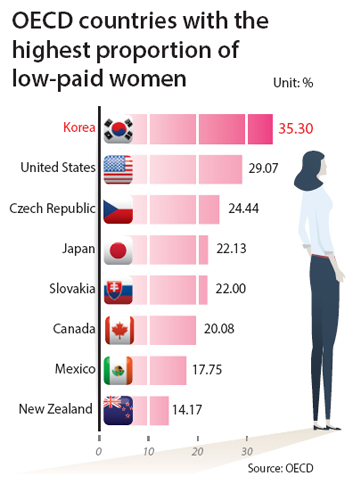

The idea that women should work under men stems from Korea’s patriarchal history. Korean culture values loyalty and the importance of gender differences (Kee 2008). Men are seen as the breadwinners, while women are responsible for housework. However, these ideal gender norms set unrealistic standards for working women since they demand that they work long hours while still taking care of their children (Cho et al. 2017). When women fail to meet these expectations, the work environment becomes hostile: they are treated as less important than men and not taken seriously. A discriminatory gender wage gap persists that invalidates women’s work (Cho et al. 2017). Furthermore, corporate businesses remain hesitant to hire married women, assuming they will most likely take leave to be a mother (Kee 2008).

These assumptions about married women mean that although women and men are both highly educated in South Korea, somehow men get all the top jobs (Kim 2009). Women have the lowest number of senior, board, and executive positions throughout Asia (Cho et al. 2017). Oftentimes, big companies are passed down to the family member’s eldest son. For example, Samsung Group, Lucky Goldstar, Ssangyong Group, and Hyundai Group are managed by the sons of the founders (Kee 2008).

Ms. Kim, a 35 year old woman, quit her job at Samsung in 2014 because she felt unappreciated within their bureaucracy and couldn’t get a top position. Through all the discrimination she faced, she was pushed out of the corporate business and decided to start her own company. She successfully created a lingerie business. As she developed her business, she faced many challenges of people rejecting her, having to assert herself when networking with men, and experiencing disrespect from her male employees (Schuman 2019).

Gender Reforms in Korea

To fix some of these issues, The Women’s Development Act was passed in 1995 to ensure gender equality in all aspects of life, and the Women’s Policy Coordination Committee was founded in 2002 to address women’s issues in the legislative branch (Republic of Korea 2000). The government adopted policies to create a greater representation of women in the labor market by enhancing the protection of their human rights through promoting women’s involvement in social activities, like volunteer work for women’s organizations (Korean Overseas Information Service 2022).

South Korea is now shifting focus to improve discrimination against women despite President Yoon and his administration fueling anti-feminist sentiment. Many feminists are putting on protests to advance women’s rights with the help of Civic labor and social groups, like Korea’s Women’s Associations United (Ahn 2022). With the protests, there is hope for the future because women feel less alone.

References

Ahn, Ashley. 2022. “Feminists are protesting against the wave of anti-feminism that’s swept South Korea”. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2022/12/03/1135162927/women-feminism-south-korea-sexism-protest-haeil-yoon.

Cho, Yonjoo, Jiwon Park, Soo J. Han, Boreum Ju, Jieun You, Ahreum Ju, Chan K. Park and Hye Y. Park. 2017. “How do South Korean Female Executives’ Definitions of Career Success Differ from those of Male Executives?”. European Journal of Training and Development 41(6):490-507. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/how-do-south-korean-female-executives-definitions/docview/1940282265/se-2.

Kee, Tan Soo. 2008. “Influences of Confucianism on Korean Corporate Culture”. Asian Profile 36(1):9-20. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Soo-Tan 4/publication/341788245_Influences_of_Confucianism_on_Korean_Corporate_Culture/links/5ed4c8f5299bf1c67d322522/Influences-of-Confucianism-on-Korean-Corporate-Culture.pdf.

Kim, Hee-Kang. 2009. “ANALYZING THE GENDER DIVISION OF LABOR: THE CASES OF THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH KOREA”. The Johns Hopkins University Press 33(2):181-299. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42704677.

Korean Overseas Information Service. 2022. “Women’s Role in Contemporary Korea”. https://asiasociety.org/education/womens-role-contemporary-korea.

Republic of Korea. 2000. “Republic of Korea”. 1-16. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/Review/responses/REPUBLICofKOREA-English.pdf.

Schuman, Michael. 2019. “Blocked in Business, South Korea Women Start Their Own.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/29/business/south-korea-women-startups-entrepreneurs.html.