When the medical profession systematically denies that existence of black women’s pain, under diagnoses our pain, refuses to alleviate or treat our pain, healthcare marks us as incompetent bureaucratic subjects. Then, serves us accordingly.

Dr. Tressie Cottom

Today, according to the CDC, Black women are 3 times more likely to die during childbirth compared to their white counterparts, while their babies are 4 times more likely to die than their white counterpart’s babies (2021). Likewise, the experiences that Dr. Cottom expressed are fairly common within the population of black pregnant women. These are real people, with real life threatening experiences of discrimination within the health care system. Through a larger lens, is how we can see the effects that race has on the quality of care given to pregnant Black women.

Systematic Racism in Maternal Health Throughout History

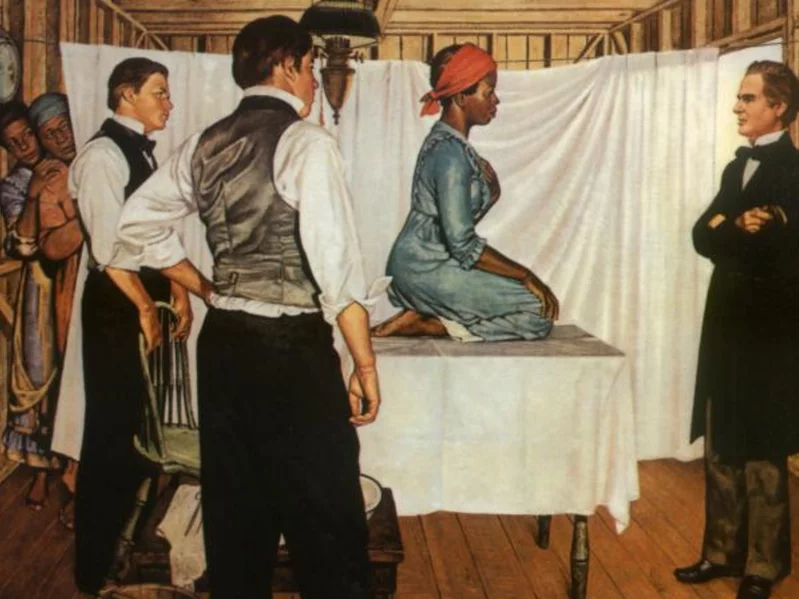

Throughout history, Black women have endured discrimination and abuse by the medical profession. During slavery in the United States, slave owners sought to increase their wealth by controlling their slaves’ reproduction. Under slavery, they sought the help of physicians to manage the Black woman’s fertility, forcing Black women to undergo injurious and painful experimental surgeries to study obstetrics and gynecology (Washington 2006).

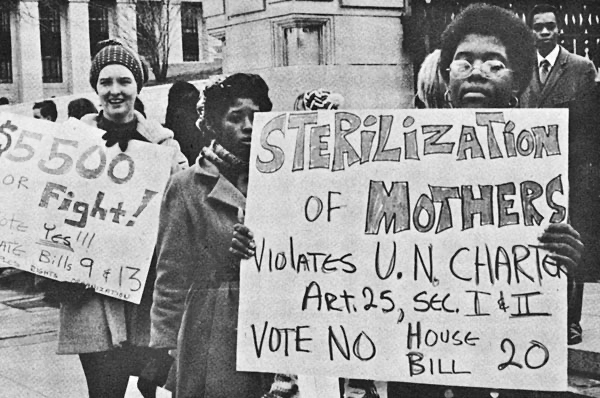

As the nineteenth century approached, eugenic control and sterilization was enacted on Black women, aimed to attack populations thought to be expendable or threatening to American society. These practices labeled Black women as bad mothers who would give rise to defective offspring (Taylor 2020). For instance, Darlene Johnson, a low-income black woman who had previously been addicted to crack cocaine, was told by a judge that she would be sent to jail if she did not use the Norplant implant (Roberts 1999). Physicians, social workers, and members of state eugenics boards worked together in the sterilization of low-income Black women with the intention of reducing the number of Black women eligible for public assistance (Marable 2004).

Today, the discrimination Black women face in medical settings has only transformed into new a form. From the long history of slavery and unethical experiments done on Black people, there is even a belief that Black people don’t feel pain. There is a false belief of us having thicker skin and less sensitive nerves, which arose from a collection of biases within medical education (Hoffman 2016). Recently, one study showed that 40% of first and second-year medical students today believe this false belief (Sabin 2020). These biases contribute to the rising mortality rates in Black maternal health. But sadly, no, we, Black women are not superhumans. Instead, because of a new form of racism, implicit bias, we are in a crisis in terms of maternal health and as a result, many, along with our babies, are dying.

The Problem is Real.

Black women are instantly dismissed when their concerns regarding their pregnancy experiences and bodies are voiced. They are often told that they are being dramatic, that they need to listen and be quiet, or that it is their fault, in which their socioeconomic status or lifestyle choices —which are usually assumed and stereotyped upon them—are the reason for these complications. These assumptions are placed on the image of our skin color because of society’s constructed perceptions of the Black woman. At the sight of a darker skin tone, we, Black women are judged, not seen, not heard, nor valued (Cottom 2019).

One step of alleviating this crisis among Black maternal health is by spreading awareness. This is a real life-threatening problem with stories that need to be heard.

Works Cited

Anon. 2022. “Working Together to Reduce Black Maternal Mortality.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 12, 2022 (https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/features/maternal-mortality/index.html).

Cottom, Tressie McMillan. 2019 , and Thick: And Other Essays. “Pregnant Black Women Are Treated as If They’re Incompetent.” Time, Time, 8 Jan. 2019, https://time.com/5494404/tressie-mcmillan-cottom-thick-pregnancy-competent/?src=longreads. Accessed April 12, 2022.

Dorothy, Roberts. 1999. The Dark Side of Birth Control. New York: Vintage Books. Accessed April 12, 2022.

Hoffman, Kelly M., Sophie Trawalter, Jordan R. Axt, and M. Norman Oliver. 2016. “Racial Bias in Pain Assessment and Treatment Recommendations, and False Beliefs about Biological Differences between Blacks and Whites.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(16):4296–4301.

Holland, Brynn. 2017. “The ‘Father of Modern Gynecology’ Performed Shocking Experiments on Enslaved Women.” History.com. Retrieved April 12, 2022 (https://www.history.com/news/the-father-of-modern-gynecology-performed-shocking-experiments-on-slaves).

Marable, Manning. 2000. “Anatomy of Black Politics.” The Review of Black Political Economy 8(4):368–83.

Sabin, Janice A. 2020. “How We Fail Black Patients in Pain.” AAMC. Retrieved April 12, 2022 (https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-we-fail-black-patients-pain).

Taylor, Jamila K. 2020. “Structural Racism and Maternal Health among Black Women.” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 48(3):506–17. Turda, M. 2007. “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present.” Social History of Medicine 20(3):620–21.

Turda, M. 2007. “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present.” Social History of Medicine 20(3):620–21.