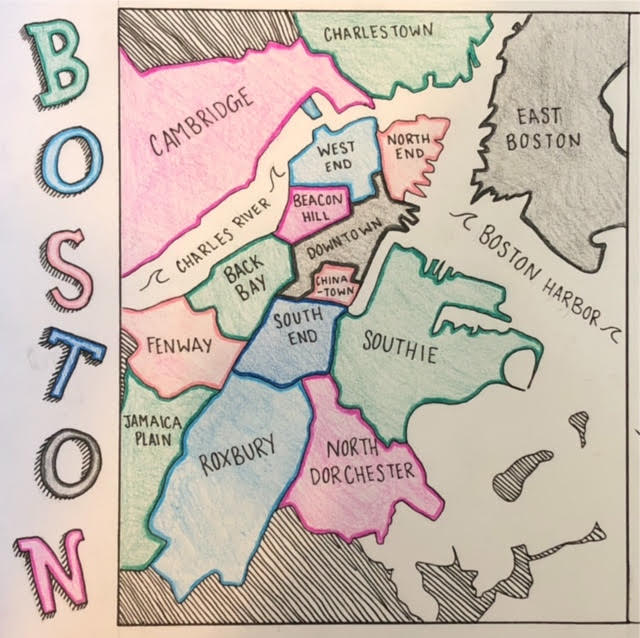

Growing up just outside of Boston and visiting the city frequently, the various ethnic sectors were always apparent to me: Southie had the Irish, the North End housed the Italians, Chinatown was home to the Chinese. These communities provide a sense of belonging to certain ethnicities who say they can embrace their culture. However, they also result from exclusion and disjointedness among the city as a whole.

Did these sections naturally develop as a result of immigration over the years, or do they represent a history of racism that still plagues the city?

Immigration

Since being founded in 1630, Boston has become home to millions of immigrants. As different groups sought refuge in the city, different cultural neighborhoods developed. In the mid 19th century, when German and Irish immigrants flooded into Boston, many of the upper class citizens migrated to Beacon Hill and the Back Bay, where they remain to this day (Puleo, 2007). At first, Irish, German, Italian, Jewish, and Portuguese citizens populated the North End. However, these groups soon migrated and settled in other areas, such as Southie, Charlestown, and Dorchester. Chinese immigrants came to Boston after World War II and settled in the center of Boston, in what is now known as Chinatown (Global Boston, 2021).

So why was housing so ethnically clustered? Was this due to choice or discrimination?

Housing & Discrimination

Many groups that immigrated pre-1930s, such as the Catholic Irish and Italians, relocated due to discrimination when integrating into white Protestant areas of Boston. For some, these developed enclaves created a sense of pride, as they felt they could express their culture (Bryson, 2021). However, this mainly occurred for white enclaves who later were accepted by the Protestants and could then easily relocate.

Segregated housing forced minorities into separate living areas, affording better living opportunities for whites. In the mid 1800s, some places could legally not be sold to minorities, such as one specific barn in Brookline that had stipulations in the deed preventing it from being sold to Irish or Black citizens (Elton, 2020). In the 1930s with redlining, city banks denied loans and services to specific geographical areas deemed “hazardous,” and specifically targeted racial minority groups (Tootell, 1996). Redlining promotes residential segregation, as minorities are denied loans in order to relocate and end up stuck in the same neighborhoods, while whites can move where they choose. Though there is evidence that some redlining occurred among groups such as the Irish, Jewish, and Italians pre-World War II, those groups have since been accepted into the white community. However, minorities such as African Americans, who populate areas such as Roxbury and Egleston Square (which lies by Jamaica Plain and Roxbury, still experience redlining today) (Leydon, 2019).

Though Boston prides itself in being a progressive city, racism and discrimination continue to shape its culturally divided geography. Black and Brown residents continue to experience severe racial discrimination and violence in predominantly white neighborhoods (Bole, 2017). Though these ethnic enclaves may enable feelings of acceptance and safety for minority groups, they prevent integration, some economic opportunities, and racial residential segregation.

So how do these divisions affect the unity in Boston?

Though people may find shelter in their own cultural communities, Boston as a whole will suffer from disjointedness if these divisions continue. In order to be united, and work together as a whole, new efforts must be made to integrate the neighborhoods of Boston and prevent racial and ethnic discrimination.

Sources

Bole, William. “Why Your Neighborhood is Still Segregated, After All These Years.” Boston

College Carroll School of Management, 21 Dec. 2017, https://www.bc.edu/bc-web/schools/carroll-school/news/2017/why-your-neighborhood-is-still-segregated–after-all-these-years.html. Accessed April 17, 2021.

BPDA Research Division. “Historical Trends in Boston Neighborhoods Since 1950.” Boston

Planning & Development Agency, 2017, http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/89e8d5ee-e7a0-43a7-ab86-7f49a943eccb. Accessed February 26, 2021.

Bryson, Emaly A. “Functions of Urban Ethnic Enclaves with a Focus on South Boston’s Ethnic

Irish Enclave in a Historical Perspective.” University of Rhode Island, 2003, https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2742&context=theses. Accessed April 19, 2021.

Elton, Catherine. “How Has Boston Gotten Away with Being Segregated for So Long?” Boston

Magazine, https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2020/12/08/boston-segregation/. Accessed April 19, 2021

Global Boston. “Boston Immigrants: Chinese.” Boston College Department of History,

https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/ethnic-groups/chinese/. Accessed March 25, 2021.

Leydon, Stephanie. “How A Long-Ago Map Created Racial Boundaries That Still Define

Boston.” GBH News, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.wgbh.org/news/local-news/2019/11/12/how-a-long-ago-map-created-racial-boundaries-that-still-define-boston. Accessed March 26, 2021.

Lima, Alvaro, and Mark Melnik. “Boston: Measuring Diversity in a Changing City.” Boston

Redevelopment Authority, Research Division, 2013, http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/32e9b68a-ce1b-41c7-808c-0395cb4f4d19. Accessed February 25, 2021.

Puleo, Stephen. The Boston Italians: A Story of Pride, Perseverance, and Paesani, from the

Years of the Great Immigration to Present Day. Beacon Press, 2007.

Tootell, Geoffrey M. B. “Redlining in Boston: Do Mortgage Lenders Discriminate Against

Neighborhoods?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 111, no. 4, Nov. 1996, pp. 1049-1079. Oxford Academic, doi:10.2307/2946707. Accessed March 25, 2021.