Anna O’Shea

“The struggle of being caged like an animal 24/7 is enough. But with all the added conditions it’s unbearable. There seems like no escape from this.”

–Jamil Hayes (currently incarcerated, letter circa American Prison Writing Archive, 2021)

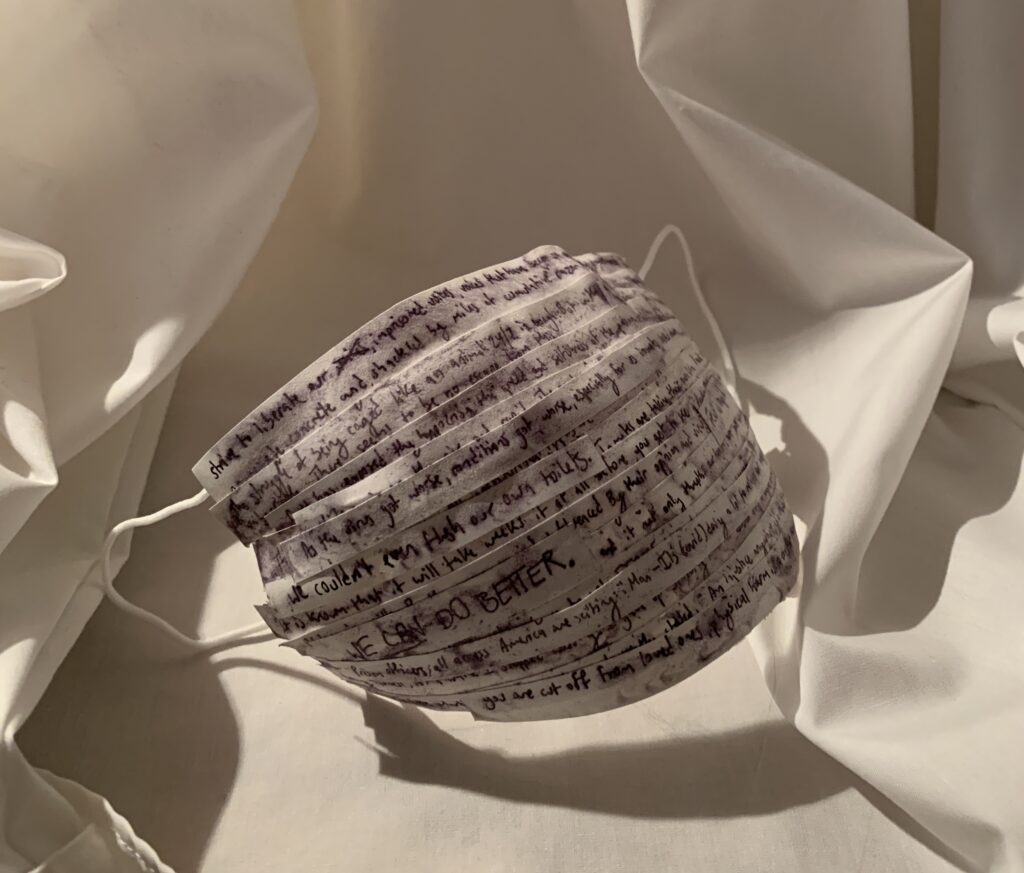

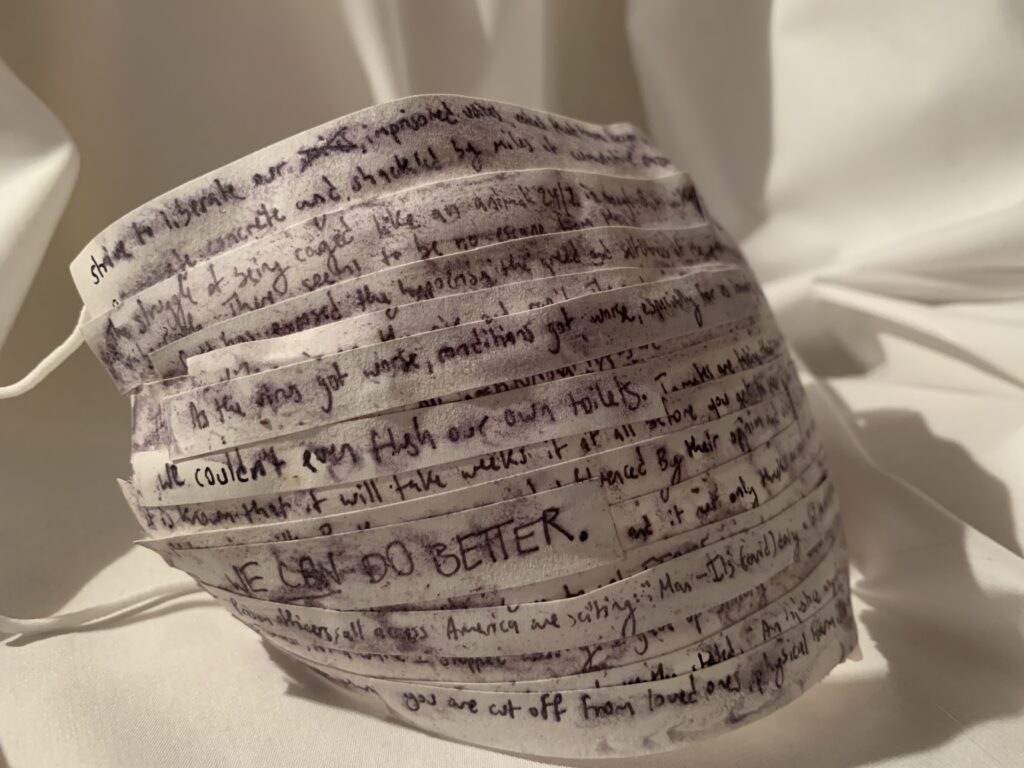

[Pictured above, collaged mask containing quotes from Jamil Hayes and other currently incarcerated people, cited from American Prison Writing Archive]

For inmates like Jamil, COVID has turned his already difficult life upside down. As of March 30th, in the United States, there have been 391,782 reported cases of the COVID-19 virus among prisoners confined by our justice system (Marshall Project 2021).

Those who populate prisons and jails have been one of the highest risk groups because of the nature of their conditions. In particular, people of color and people with underlying health conditions have been affected in large numbers in the United States because of their incarcerated status.

Where Are the Biggest Risk Areas?

Epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves from Yale School of Medicine and School of Public Health states “Incarcerated persons contract the virus at a rate of at least four times the rate of the overall U.S. population and, once infected, are over twice as likely to die,” (Yan 5).

While one of the best ways to avoid the virus spreading is through social distancing, it is logistically impossible in detention spaces. Sites of detention include those in criminal detention (jails and prisons), pretrial detention (non-criminal jail time), custody of ICE, and mandated substance abuse/juvenile detention. Extremely close proximity, confined spaces with poor ventilation, and lack of access to sanitary products make these sites of detention the perfect breeding ground for dangerous and rapid spreading of potentially deadly germs (Garrett & Kovarsky 2021).

So Who’s at Risk?

Certain groups are greatly overrepresented in our incarcerated population and therefore must suffer a greater risk of exposure. For jails and prisons, inhabitants are much more likely to possess underlying and chronic health conditions that are worsened by the conditions and lack of effective medical infrastructure in these facilities. This means they are at a much greater risk of contracting and possibly dying from the virus (Garret & Kovarsky 2021).

Due to the foundation of our justice system on the basis of racial prejudice against Black Americans, they are also largely overrepresented in our incarcerated population (Crossley 2021). As of March 23rd, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, 38.6% of current inmates were Black, even though Black people only make up 13.4% of the population (US Census Bureau). This means that race is another factor that increases disproportionate risk of Black people and other people of color contracting COVID.

Could We Have Avoided This?

Gregg Gonsalves, in his affirmation to the NY Supreme Court, made an argument similar to the World Health Organization recommending decarceration as the most viable option to minimize the risk of COVID cases rising exponentially in the incarcerated population (Yan 2021). However, the United States justice system failed to act on this recommendation. In addition, the Federal Bureau of Prisons denied a large majority of submitted compassionate release pleas (Garrett & Kovarsky 2021).

Jamil and hundreds of thousands of other prisoners have faced unbearable conditions and life-threatening health risks due to their state of incarceration. This global health crisis has revealed large systemic problems that must be addressed in our justice and health care system. Accountability must be taken for the safety of imprisoned people, and the only way to humanize them is by telling their stories and unmasking the truth.

Works Cited

“Federal Bureau of Prisons.” BOP Statistics: Inmate Race, 2021, www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp.

Crossley, Mary. “Prisons, Nursing Homes, and Medicaid: A COVID-19 Case Study in Health Injustice.” Annals of Health Law and Life Sciences, Forthcoming, U. of Pittsburgh Legal Studies Research Paper 2021-04 (2021).

Garrett, Brandon L., and Lee Kovarsky. “Viral Injustice.” California Law Review, Forthcoming (2021).

Hayes, Jamil. “Being Incarcerated during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” American Prison Writing Archive at Hamilton College, 2021, apw.dhinitiative.org/islandora/object/apw%3A12361872.

Magnitic, Roc. “American Prisons and Free-World Staff Not Ready for Second Wave of COVID.” American Prison Writing Archive at Hamilton College, apw.dhinitiative.org/islandora/object/apw%3A12361864?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=d6bc1804afee6b0b4192&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0.

“A State-by-State Look at Coronavirus in Prisons.” The Marshall Project, The Marshall Project, 25 Mar. 2021, www.themarshallproject.org/2020/05/01/a-state-by-state-look-at-coronavirus-in-prisons.

United States Census Bureau , U.S. Department of Commerce, 2019, www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219.

Williams, Dortell. “An Open Letter to Congress: National COVID-19 November Mail-in Voting ‘We Can Do Better.’” American Prison Writing Archive at Hamilton College, 2020, apw.dhinitiative.org/islandora/object/apw%3A12360277?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=acc1bdfa16e5e5893f06&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=1.

Williams, Dortell. “COVID-19 and Prison Overcrowding: Its All in the Framing.” American Prison Writing Archive at Hamilton College, 2020, apw.dhinitiative.org/islandora/object/apw%3A12360179?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=5d53e8a709c95b55dc1d&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=3.

Yan, Holly. “The Risk Posed by Infectious Disease in Jails and Prisons is Significantly Higher than in the Community.”