Pictured above: 1950’s posters for boy scouts and girl scouts by Normal Rockwell. Put together here in a collage to show the seriousness portrayed by BSA compared to GSUSA’s more playful attitude.

There is a reason why the Girl Scouts of the United States of America (GSUSA) have had a century-long identity crisis on their hands: they are constantly playing catch up with the boys. By creating gender-segregated spaces, the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) and GSUSA have contributed to a form of cultural sexism that places greater value on traditionally masculine traits and abilities1. Using merit badges as affirmation for achieving gender behaviors valued over a century ago, these organizations have reinforced a problematic snapshot of history, one that depicts women as the inferior gender attempting to reconcile acts of femininity and masculinity.

Comparing Badges

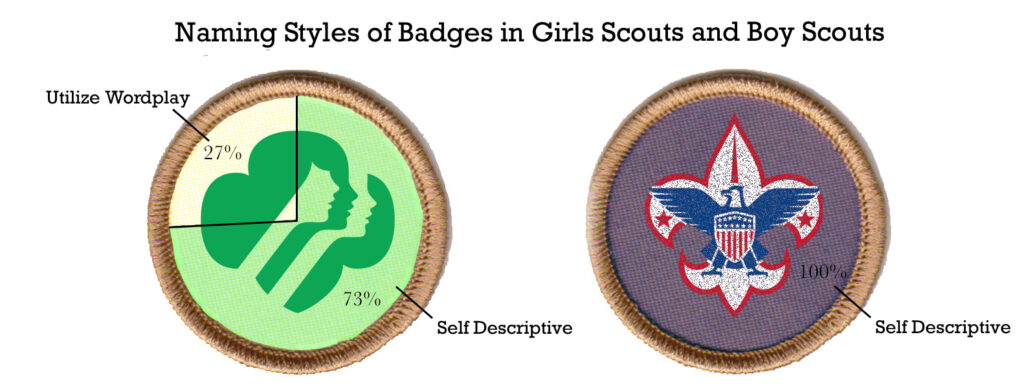

Word choice may seem trivial in the large scope of perpetuating gender inequality, but badge naming styles show a divergence in how practical boys and girls perceive their learned abilities. For example, boys when receiving the “digital technology” badge are made to feel that their achievement can translate to useful scenarios. On the other hand, GSUSA when giving out their “netiquette” badge which rewards similar online abilities, puts girls at a disadvantage by making comparable achievements to boys feel less legitimate or practical.2 With playful badge titles, girls are receiving tailored versions of awards that conform to classical perspectives of femininity.

What These Badges Reward

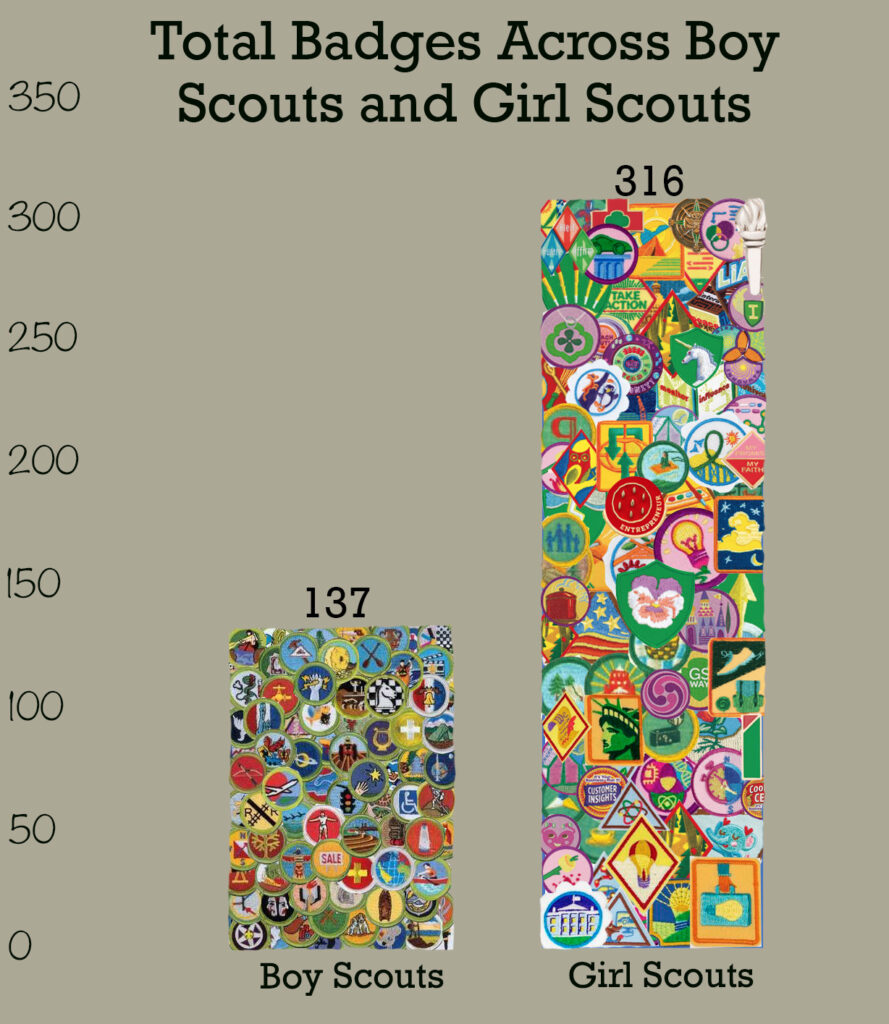

Among BSA’s 137 badges, many reward stereotypical masculine behaviors such as “welding”, “truck transportation”, and “shotgun shooting.” It is worth noting that although not all favor such traditional masculine acts, only a handful of badges in BSA’s catalog, such as “gardening” or “cooking”, reward acts that can be considered remotely effeminate. This is where looking at GSUSA to see how gender is approached through badges gets really interesting. Instead of shifting the focus of merit badges away from classic symbols of femininity, GSUSA has opted to dilute its history by rebranding old achievements and amassing a staggering 316 badges covering a wide variety of topics.3 While members may choose to pursue achievements for being a “savvy shopper” or “dinner party planner,” they can also learn about more normative masculine interests such as “automotive design” or “woodworking.”

It Takes Two

The relationship between these organizations and their accompanying discrepancies has educated children for over a century on how to adhere to traditional masculine and feminine classical gender roles. BSA’s more narrow focus on badges reaffirms some young men’s belief that their masculinity is favorably received not only by acting in traditionally masculine ways, but also by refraining from expressing stereotypical femininity.4 This narrow scope of badges exemplifies the more confined boundaries of masculinity.

Meanwhile, GSUSA through its eclectic catalog represents a wider perspective of gender conformity that exists for girls.5 This broader view on gender is shown through the organization’s larger quantity of badges and acceptance of traditionally masculine acts. The girl scout’s acceptance of these acts in comparison to boy scout’s avoidance of femininity can be seen as a manifestation of cultural sexism. Through these badges, BSA and GSUSA can continue to instill a historical perspective of gender onto their members, educating young boys and girls to the degree they can acceptably operate within their birth-assigned gender norms.

Sources: Featured images are edited versions of art by Norman Rockwell.

Girl Scout portrait: https://www.nrm.org/2012/09/norman-rockwell-museum-to-present-girl-scout-festival-a-centennial-celebration/good_scouts_web/

Boy Scout portrait: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/04/arts/design/04rockwell.html

All images of badges are taken directly from the Boy Scouts of America and Girl Scouts of United States of America websites.

Footnotes: 1-Connell, Raewyn. Gender, Health and Theory: Conceptualizing the Issue, in Local and World Perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 2011, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953611003509.

Badge naming breakdown data, 2, and 5- Denny, Kathleen E. “Gender in Context, Content, and Approach.” Gender & Society, vol. 25, no. 1, 2011, pp. 27–47., doi:10.1177/0891243210390517.

3- Anderson, Erin K., and Autumn Behringer. “Girlhood in the Girl Scouts.” Girlhood Studies, vol. 3, no. 2, 2010, doi:10.3167/ghs.2010.030206.

4-Lynn, Carol, and Diane Ruble. “Patterns of Gender Development.” National Center for Biotechnology Information, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3747736/?report=classic.