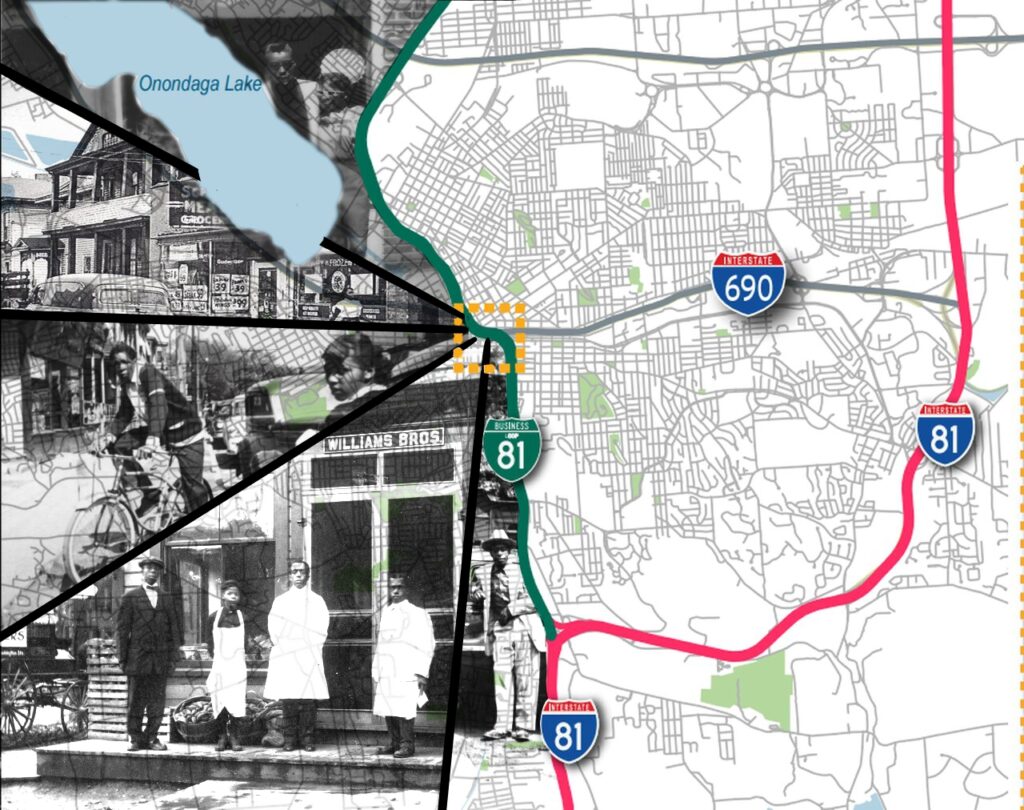

Images from top to bottom: Martin Irons and Clara Brown at a storefront in 1956; Schor’s Market on Harrison Street in 1965; Teenagers outside of Aunt Edith’s Luncheonette in 1950; The owners of the Williams Brothers’ Grocery stand in front of their store in 1920; George Hayden in front of Hayden grocery store in the 15th Ward.

This artistic tribute pays homage to the history of the 15th Ward, the historically Black neighborhood destroyed to make way for the construction of Interstate 81 in Syracuse, NY. The images on the left side of the map give a glimpse into life in the 15th Ward before its decimation. The route in green shows the current path of the Interstate, while the route in red indicates the planned rerouting of traffic after infrastructure reforms, which will create a “community grid” in the area marked by the dotted yellow box. The community grid aims to reduce the de facto segregation of the city resulting from I-81. (Image Sources: Washington Post, The Atlantic, Black Syracuse, Syracuse.com)

When construction began on Interstate 81, the project was part of a larger effort to connect the United States through extensive infrastructure revitalization. The national roadway connects Tennessee to the northern reaches of New York, where it crosses Canada’s border to become Highway 401. The major highway cuts through the city of Syracuse, New York, a centrally located hub of commerce in the state.

Construction on Syracuse’s stretch of I-81 started in 1959, and the project was widely lauded as an exciting opportunity to bolster the local economy; in reality, however, it decimated the 15th Ward, a historically Black neighborhood and initiated a period of “white flight” that would shape the city for generations.[1]

Discrimination and Destruction in the 15th Ward: A Lasting Legacy

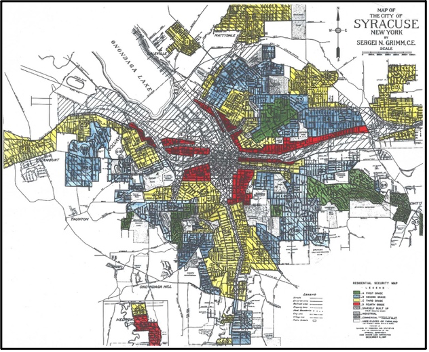

Discriminatory redlining practices in the 1930s which left residents of Syracuse’s 15th Ward with little ability to gain financial backing from banks to revitalize their local area. Further, the city declared that redlined areas were “slums” and refrained from investing urban renewal funds there.[2] As a result, the 15th Ward and other neighborhoods populated predominantly by Black residents were marked for destruction to make space for I-81.

Now, not only are the city’s predominantly Black and brown communities battling centuries of historical oppression through law and social customs, they also face a physical barrier to better health outcomes, educational institutions, and economic opportunities.

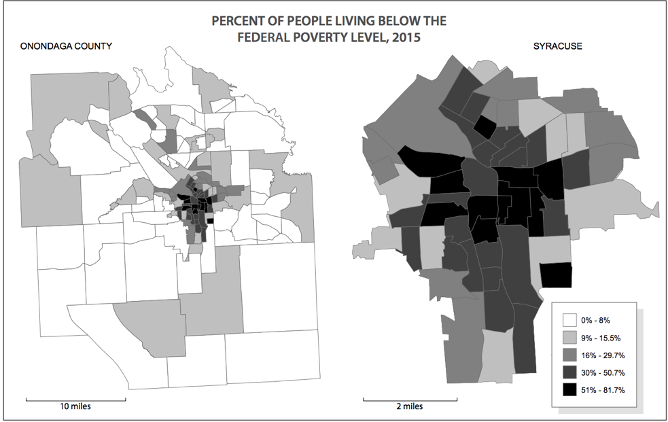

Past discriminatory policies in housing, transportation, and education have resulted in alarming levels of poverty in the Black and Hispanic communities in Syracuse; in fact, a local news outlet reported in 2015 that the city was found to have the highest rate of extreme poverty among Black and Hispanic populations among America’s 100 largest metropolitan areas.[3]

Additionally, predominantly Black communities on the western side of the highway face catastrophic health effects due to their proximity to heavy traffic, such as hospitalizations due to asthma that are twice as high in the downtown areas as they are in the suburbs.[4] A report by the NYCLU states that Black residents have higher rates of both lead exposure and asthma than white people living in Syracuse as a result of the proximity to heavy traffic.[5]

The Future of I-81: Proposals and Plans

The elevated segment of I-81 that was built upon the 15th Ward has been a source of continuing, nuanced debate amongst city, state, and federal stakeholders. Community activists, especially those from the most heavily impacted neighborhoods, have pushed for infrastructure reform and have successfully brought the Interstate’s negative effects to the attention of the public. The Onondaga Citizens League conducted a report of potential effects that could emerge from reform of the highway in 2008, concluding that demolishing the elevated portion of I-81 and replacing it with an urban boulevard would have both economic and environmental benefits for the city of Syracuse.[6]

Eventually, the Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council (SMTC) conducted an audit of the problems presented by I-81 and proposed three main options for reform: a “no-build” option, which would involve only routine maintenance and repairs without altering the main configuration of the roadway; a viaduct option, which would involve demolishing the existing elevated portion of the highway and replacing it with a similarly structured stretch of road; and a community grid option, which would involve the demolition of the existing viaduct and the creation of a surface street complete with bicycle lanes and pedestrian routes whilst enhancing nearby high-traffic roadways such as I-481, which runs around the downtown area of the city.[7]

Most community advocates and public interest advocacy groups favored the community grid alternative, seeing the value in removing the physical barriers that segregate the city and lead to disparate outcomes for certain neighborhoods and demographic populations. In 2019, planners decided to commit to the community grid alternative which will begin construction in the summer of 2022.[8] Despite the potential this infrastructure holds, it is integral to remember the communities which were sacrificed against their will in the name of innovation and economic opportunity, despite being denied those same opportunities for generations. The outlook for the community grid system is positive, but the city, state, and federal officials involved with Syracuse’s development, as well as the city community as a whole, will have to continue the fight in pursuit of racial justice on all fronts.

[1] Semuels, Alana. “How to Decimate a City.” The Atlantic. May 29, 2016. Accessed March 31, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/11/syracuse-slums/416892/.

[2] Samuels, Robert. “How a Crumbling Road in Syracuse Is Sparking a Conversation about Reparations.” The Washington Post. October 20, 2019. Accessed March 31, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/10/20/how-crumbling-bridge-syracuse-is-sparking-conversation-about-reparations/?arc404=true.

[3]Weiner, Mark. “Syracuse Poverty Worst in Nation for Blacks, Hispanics.” Syracuse. September 06, 2015. Accessed March 31, 2021. https://www.syracuse.com/news/2015/09/syracuse_has_nations_highest_poverty_concentrated_among_blacks_hispanics.html#:~:text=SYRACUSE, N.Y., study of poverty in America.

[4] Samuels, Robert. “How a Crumbling Road in Syracuse Is Sparking a Conversation about Reparations.” The Washington Post. October 20, 2019. Accessed March 31, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/10/20/how-crumbling-bridge-syracuse-is-sparking-conversation-about-reparations/?arc404=true.

[5] “Building A Better Future.” New York Civil Liberties Union. January 07, 2021. Accessed March 31, 2021. https://www.nyclu.org/en/publications/building-better-future.

[6] Armstrong, Anthony, and Make Communities. Deconstructing Segregation in Syracuse? The Fate of I-81 and the Future of One of New York State’s Highest Poverty Communities. Report. Poverty & Race Research Action Council. Housing/Schools Field Report. 2018.

[7] Armstrong, Anthony, and Make Communities. Deconstructing Segregation in Syracuse? The Fate of I-81 and the Future of One of New York State’s Highest Poverty Communities. Report. Poverty & Race Research Action Council. Housing/Schools Field Report. 2018.

[8] “Officials Breathe New Life into Syracuse’s I-81 Redesign Project.” Oswego County Business Magazine. Accessed March 31, 2021. http://www.oswegocountybusiness.com/special-features/officials-breathe-new-life-into-syracuses-i-81-redesign-project/.