Recently, The New York Times has been running a series of articles on white people calling the police on black people for innocuous activities. A summary article published on October 22nd highlighted thirty-nine recent incidents from this past year, many of which have taken place in suburban areas across the United States. In just October, white people have called the police on black people buying drinks at a gas station, at a father yelling at a son at a soccer game and when a black man was babysitting two children. These incidents took place in suburban locales: Ponte Vedra, Florida (suburb of Jacksonville, Florida), North Charleston, South Carolina (suburb of Charleston, South Carolina) and Marietta, Georgia (suburb of Atlanta, Georgia).

While the calls to the police have also occurred in cities, a cursory glance at The New York Times list revealed a majority took place in suburbs and/or small cities. These racist phone calls are motivated by white residents feeling uncomfortable with having black people in their midst. As suburbs are increasingly diverse, white residents used to homogenous communities are responding to an increased influx of black residents and visitors with reactionary racist fear. The legacies of zoning and exclusionary organizations such as Residential Community Associations (RCA) have directly led to this by creating all white homogenous communities.

The basis of these calls have little to due with the activities black people are partaking in (such as a woman using a coupon at a pharmacy, or a women attempting to cash a check at a bank), but with perceptions of place and space. Black people in white spaces are viewed as invasive, and therefore any activity they take part in, no matter how benign, are viewed as invasive. Black people are seen as violating a boundary, and disrupting the “natural flow” of activities in any given area.

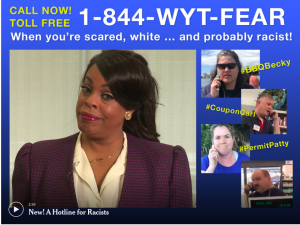

Below I have included the link to The New York Times summary article, as well as a selection of articles on recent incidents in September and October. In collaboration with actress Niecy Nash, The New York Times created a satirical video advertising 1-844-WYT-Fear, a hotline for white residents perturbed by the site of black people going about their lives.

New York Times overview: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/opinion/calling-police- racism-wyt-fear.html

Incidents from September and October:

North Charleston, South Carolina – The Charleston City Paper

Ponte Vedra, Florida – First Coast News

Brooklyn, New York – The New York Times

Marietta, Georgia – CBS46

Boston, Massachusetts – The Charlotte Observer

Dane County, Wisconsin – The New York Times

Amherst, Massachusetts – Associated Press