Olivia Rubano

Ferries are historic to New York City. The city is interwoven in water, and throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, ferries were a logical mechanism of transportation (Glowinski). Over the past century, New York City’s ferries have peaked and then declined due to urban renewal (Glowinski). Ferries have become more popular in New York City in recent years (Mcgeehan). Their resurgence has made apparent their changed relationship with the city due to urban renewal and the rise of subways and has presented issues of accessibility and equity because of the location of their stops and their fare.

A New York City ferry in the 1920’s (Old NYC Photos).

In 1904, 147 ferry boats were in operation, and in 1905, the city took control of the ferry system (Glowinski). The system went through a period of growth from 1918-1925 due to new boats, new boat designs, and devising new ferry routes (Glowinski). When the stock market crashed in 1929, the New York ferry system began to decline (Glowinski). There was suddenly less revenue and, thus, less available money to spend on ferries (Glowinski). However, the available funds went toward automobile infrastructure (Glowinski). Through the 1960s, New York City underwent rapid urban renewal, and ferry routes were replaced by bridges and tunnels (Glowinski). Operating from 1920 to 1936, the ferry route between 92nd Street and Astoria was replaced by the Triborough bridge, an urban renewal project spearheaded by Robert Moses, New York’s “larger-than-life administrator who headed the most important state and city redevelopment agencies in New York City from the 1930s to the 1960s” (Glowinski; Zukin 13; NYPAP). The Class Point to College Point ferry route ran from 1921 to 1939 until the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge was constructed, another project lead by Robert Moses (Glowinski; NYPAP). Beyond these two bridges, many of Moses other projects, like parkways and highways, opened the city up to cars, leading to the decline of ferries.

The Triborough Bridge, built in 1936, which opened the city up to automobiles (Wikipedia).

Ferries serve as an echo of a New York city before increased automobile infrastructure and Robert Moses, and in recent years, there has been a resurgence in New York City ferries due to their low fare of $2.75 and overall charm compared to the “beleaguered subway system” (Mcgeehan). On April 28th, the ferry system reached one million riders in the first thirteen weeks of 2023 (NYCEDC). Thirteen weeks is the earliest that the New York City Economic Development Corporation and NYC Ferry has ever recorded reaching this many riders (NYCEDC). This resurgence has not come without its issues. In 2017, demand for ferries outstripped supply (Goodman and Mcgeehan). Crowds were showing up to board, and there was not enough room to fit all the passengers (NYT). The city had to charter more boats, larger boats, but that takes time (Goodman and Mcgeehan). A spokesman for City Hall, Wiley Norvell, explained that, “Some of this is going to be trial and error. We’re not the subway. We don’t have 70 years of detailed ridership telling us how many trains to run after a Yankee game” (Goodman and Mcgeehan). Despite ferries being historically intertwined with the city, the decline set on by urban renewal has disrupted this relationship, introducing unknowns.

Additionally, because of the rise of subway systems, ferries are not always perceived as convenient; ferries often have 30-minute intervals between departures whereas their rival transportation has mere minutes (Kahn; NYC FERRY “New York NYC Ferry Routes & Schedules”). Ferries serve those who have the luxury of time. Millions of people in New York City take the subway everyday; one million people took the ferries over three months (Mcgeehan). Despite their come back in recent years, ferries are no longer a vital organism of the city, and rivers do not serve as “natural roads” in the same way they did in the 19th and 20th centuries (Glowinski).

A New York City ferry in front of the Empire State Building (Wikipedia).

Moreover, ferries are not equally accessible to everyone, but with new government efforts, there is opportunity for the city to address these issues. In 2019, twelve of NYC’s nineteen stops were in areas where per-capita annual incomes exceeded the city’s average; seven of those stops had per-capita annual incomes that were twice the city’s average (Hicks). The ferry was most accessible to wealthier people. In 2022, the Mayor Eric Adam’s proposed the Ferry Forward plan. The goals of this plan are to make the ferry system more equitable, accessible, and financially sustainable (NYC Ferry “Cruising towards Another Record-Setting Year”). Cortney Worrall, CEO of Waterfront Alliance, which protects New York/New Jersey Harbor, thinks that with this plan, “There is great opportunity to expand services to new locations, to identify transit deserts that would be well-served by ferries” (City of New York; Waterfront Alliance). In order to make ferries equitable, ferry stops need to be located in a variety of communities, not just wealthy ones.

Beyond ferry stops, ferry fares also present issues of equity. The New York City ferry system does not generate enough revenue to cover operation costs, and a significant cost burden falls on tax payers (Meyer and Hicks). Typically, those riding the ferries are wealthier, having median annual incomes of $100,000-150,000 (Meyer and Hicks). These typical riders will be able to supply an increase in fare, and in the Ferry Forward plan, Mayor Eric Adams raised the one way rate from $2.75 to $4.00 (Meyer and Hicks). If only this action was taken, predominantly wealthy ridership would likely be perpetuated because lower income riders may seek cheaper alternatives to ferries like the subway (Meyer and Hicks; MTA “Riding the Subway”). However, Mayor Adam’s Ferry Forward plan does work to address income disparities and equity, offering seniors and ferry riders with lower incomes and disabilities the discounted rider rate of $1.35 (City of New York). The Ferry Forward Plan was released in July of 2022, and ridership has increased in 2023 (NYCEDC). In order to determine if ridership increased because of discounted fares aimed to make ferries more equitable, new data must be collected and should be announced to the public.

A New York City ferry journey near the Brooklyn Bridge (NYCEDC).

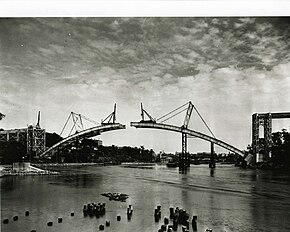

It is essential that people are not further isolated from the waterways that intersect New York City. In 1936, Robert Moses built the Henry Hudson Bridge, destroying residential areas and green spaces along the Harlem River (Carr; Gray; MTA “Henry Hudson Bridge”). More recently, clean up efforts have caused the Hudson River’s banks to be the site of gentrification, pushing out existing communities (Turrin). To truly restore ferries as a mode of transportation within the city, it is critical to consider whether ferries are truly ingrained in New York City as a whole or if they serve as an embellishment for those who are privileged enough to partake.

The construction of the Henry Hudson Bridge (Wikipedia).

Sources

Carr, Ethan. “The Hudson River Waterfront: Recollections and Observations.” SiteLINES: A Journal of Place 3, no. 2 (2008): 8–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24889304.

City of New York. “Mayor Adams Unveils Phase One Of.” The official website of the City of New York, July 14, 2022. https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/505-22/mayor-adams-phase-one-nyc-ferry-forward-vision-more-equitable-accessible-#/0.

Glowinski, Patricia. “The Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of the New York City Municipal Ferry System.” NYC Department of Records & Information Services, October 9, 2019. https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2019/7/29/ferries.

Goodman, J. David, and Patrick Mcgeehan. “NYC Ferry, More Popular than Expected, Scrambles to Meet Demand.” The New York Times, June 15, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/15/nyregion/nyc-ferry-more-popular-than-expected-scrambles-to-meet-demand.html.

Gray, Christopher. “Streetscapes/Henry Hudson Bridge; a Controversial ’36 Span through Dreamy Isolation.” The New York Times, August 10, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/10/realestate/streetscapes-henry-hudson-bridge-controversial-36-span-through-dreamy-isolation.html.

Hicks, Nolan. “City Ferry Mostly Benefits the Wealthiest New Yorkers.” New York Post, April 1, 2019. https://nypost.com/2019/03/31/city-ferry-mostly-benefits-the-wealthiest-new-yorkers/.

Kahn, Sonia. “What Goes up Must Come down: A Brief History of New York City’s Elevated Rail and Subway Lines: Worlds Revealed.” The Library of Congress, May 19, 2022. https://blogs.loc.gov/maps/2022/05/what-goes-up-must-come-down-a-brief-history-of-new-york-citys-elevated-rail-and-subway-lines/.

Mcgeehan, Patrick. “New York City’s Ferry Fleet Is off to a Fast Start.” The New York Times, November 29, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/29/nyregion/new-york-ferry.html.

Meyer, David, and Nolan Hicks. “Adams Seeks NYC Ferry That Can Break Even – or at Least Not Soak Taxpayers.” New York Post, September 8, 2022. https://nypost.com/2022/09/08/nyc-seeks-guaranteed-revenue-from-its-costly-ferry-service/.

MTA. “Henry Hudson Bridge.” MTA, July 10, 2023. https://new.mta.info/bridges-and-tunnels/about/henry-hudson-bridge.

MTA. “Riding the Subway.” MTA, August 20, 2023. https://new.mta.info/guides/riding-the-subway#.

NYCEDC. “NYCEDC and NYC Ferry Announces Record Breaking Ridership Numbers.” NYCEDC, April 28, 2023. https://edc.nyc/press-release/nycedc-and-nyc-ferry-announces-record-breaking-ridership-numbers#:~:text=These new ridership numbers build,of the ridership share respectively.

NYC Ferry. “Cruising towards Another Record-Setting Year.” New York City Ferry Service, March 23, 2023. https://www.ferry.nyc/blog/cruising-towards-another-record-setting-year/#:~:text=New%20York%20City%27s%20NYC%20Ferry,with%20disabilities%2C%20and%20Fair%20Fares.

NYC FERRY. “New York NYC Ferry Routes & Schedules.” New York City Ferry Service. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.ferry.nyc/routes-and-schedules/.

NYPAP. “Robert Moses.” NYPAP. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.nypap.org/preservation-history/robert-moses/#:~:text=He was principally responsible for,Verrazano Narrows Bridge, the Westside.

Turrin, Margie. “Issues of Inequity Explored by the next Generation of Hudson River Educators.” State of the Planet, November 10, 2021. https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/08/29/issues-of-inequity-explored-by-the-next-generation-of-hudson-river-educators/.

Waterfront Alliance. “About Us.” Waterfront Alliance. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://waterfrontalliance.org/who-we-are/about-us/.

Zukin, Sharon. Naked City: The death and life of authentic urban places. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Images

Ferry in front of Empire State Building. Wikipedia. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NYC_Ferry.

Ferry near Brooklyn Bridge. EDC. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://edc.nyc/project/nycferry.

Henry Hudson Bridge construction. Wikipedia. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Hudson_Bridge.

Triborough Bridge. Wikipedia. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_F._Kennedy_Bridge.

1920s Ferry. Old NYC Photos. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://oldnycphotos.com/products/manhattan-municipal-ferry-new-york-n-y-1920.