By Maeve Sebold

COVID-19 has had and continues to have drastic impacts on individuals, communities, and industries across the globe. One of these effects is population change. Two of the main population changes resulting from the pandemic are migration out of dense cities into outlying suburbs and reduced immigration. Although many people have left cities, a significant percentage of these individuals were bound to move out anyway; thus, cities need to turn their attention to attracting new residents and immigrants and not focus on those who left.

There are several factors influencing the “flight from density” (Brookings). First, the pandemic led to an increase of remote work. More and more employers realized they could shift to work from home with ease by utilizing platforms such as Zoom. Suburbs are generally also more affordable and provide more space, both indoors and outdoors. There was also an increased desire for guesthouses and separate “in-law suites,” as many families took elderly relatives out of nursing homes and more immediate family members, like adult children, returned home.

This “flight from density,” however, is notably more possible for those of higher socioeconomic status. Ben Popken of NBC News stated that “it’s a K-shaped recovery. Wealthy people are doing well, and affluent people are more able to work remotely.” The socioeconomic component to suburban life is central. “While people across incomes continued to move around as they had before the pandemic, it was higher-income zip codes that saw a sharp change in movement at the height of the pandemic” (Bloomberg). Remote work serves as an “additional release valve” for pricey housing markets. However, this release valve is not available to those who need it the most. Most of the American work force, including essential workers and low-wage workers, are unable to work remotely. Their jobs are also often located in dense, urban centers, so suburban life is not a viable choice for many lower socioeconomic classes.

There have been some questions regarding if these migrations out of the city were a result of the pandemic or if they rather aligned with historical patterns. A study done by the Cleveland Federal Reserve discovered that the “mass exodus” out of cities was not actually out of step with historical precedent and was in fact due more to a loss of in-migration than departures.

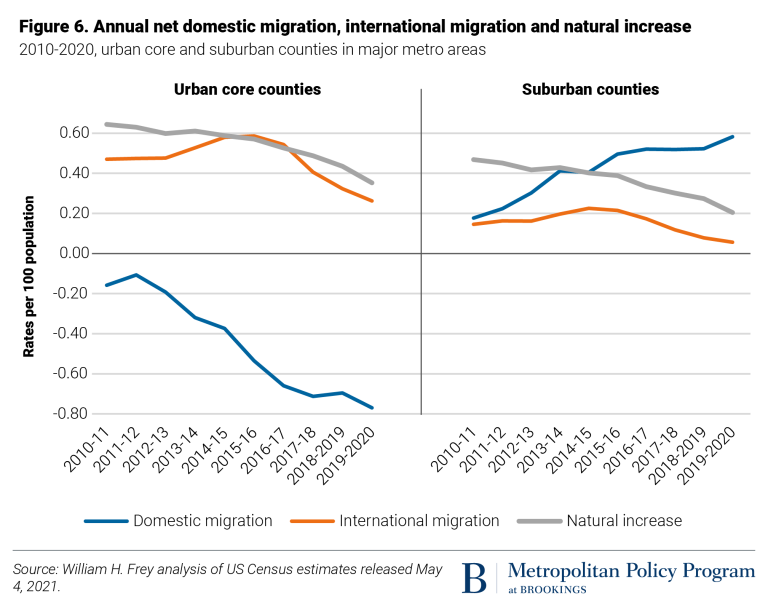

Throughout modern U.S. history, “departures have always exceeded arrivals in large cities” (Slate). Historically, immigrants and “natural increase,” or new births have counterbalanced this. During the pandemic, however, immigration significantly dropped. “Monthly green cards issued to immigrants abroad fell from 40,000 a month in 2019 to fewer than 5,000 in April, May, June, and July of 2020” (Slate). There is also a backlog on visa and immigration processing, which can potentially negatively impact dense cities.

Although there were changes in immigration policies during the Trump administration, namely a focus on restricting immigration, the numbers were largely in step with previous decades. “With the exception of refugee admissions, there has not been a dramatic, across-the-board “Trump effect” attributable either to the administration’s policies or rhetoric on immigration levels” (MPI). Immigration did, however, see a drastic reduction during the pandemic. “And while Trump acted to limit mobility in response to the coronavirus outbreak, trends suggest that immigration was dropping in advance of his proclamations” (MPI).

Susan Wachter, a professor at Wharton School UPenn, told NBC that “the pandemic has fast-tracked long-term demographic shifts.” The pandemic compressed moves that would have happened a few years down the line that were inevitable. However, this only relates to in country, domestic moves and does not account for loss of immigration.

In an article published by Bloomberg, titled “More Americans Are Leaving Cities, But Don’t Call It an Urban Exodus,” the authors state that this phenomenon is less of an “urban exodus” and more of an urban shuffle.” The data shows that most people who moved “stayed close to where they came from… In the country’s 50 most populous cities, 84% of the moves were to somewhere within the perimeter of the central metro area” (Bloomberg).

So, although many are leaving cities during the pandemic, “the key to survival will not be focusing on those who have left – they did always want that yard – but on those who have not yet arrived,” specifically immigrants (Slate). For example, Michael Hendrix, Director of state and local policy at the Manhattan Institute, is concerned about attracting new talent to New York City. Hendrix believes the city needs to consider “whether New York is attractive to new people again and not just for the rest of the country but the rest of the world.”

Migration patterns are important as they can affect “housing prices, tax revenue, job opportunities and cultural vibrancy” (Bloomberg). Thus, urban areas and neighborhoods like New York City, need to focus on what attracts people, namely immigrants, to live there in the first place. Policy makers need to concentrate on what makes dense urban areas attractive, such as increased housing, protective tenant practices, a social safety net, clean public areas, aid for small businesses, and more public spaces (Slate).

Sources:

Bolter , Jessica, and Muzaffar Chishti. “The ‘Trump Effect’ on Legal Immigration Levels: More Perception Than Reality?” Migrationpolicy.org, 8 June 2021, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/trump-effect-immigration-reality.

Frey, William H. “Pandemic Population Change across Metro America: Accelerated Migration, Less Immigration, Fewer Births and More Deaths.” Brookings, Brookings, 20 May 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/research/pandemic-population-change-across-metro-america-accelerated-migration-less-immigration-fewer-births-and-more-deaths/#:~:text=Together%2C%20low%20immigration%2C%20more%20deaths,in%20at%20least%20120%20years.

Grabar, Henry. “The Real Problem Facing American Cities.” Slate Magazine, Slate, 22 Feb. 2021, https://slate.com/business/2021/02/us-cities-shrinking-why-new-york-los-angeles.html.

Patino, Marie, et al. “More Americans Are Leaving Cities, But Don’t Call It an Urban Exodus.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-citylab-how-americans-moved/.

Popken, Ben. “Millions of Americans Moved During the Pandemic – and Most Aren’t Looking Back.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 11 Jan. 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/millions-americans-moved-during-pandemic-most-aren-t-looking-back-n1252633.