Post by Luke Zaelke

To some, mining seems like a distant concept reserved for people and places that exhibit a historical geologic presence. One might think of old mining towns in the western United States, or coal mines in England during the industrial revolution. But some inhabited areas exhibit no mining value until new technologies reveal the hidden treasure, thus creating tension between the place’s current use and the possible founding of a mine. This tension reveals issues of preservation, founding, and environmental justice. The 2017 La Colosa Mine controversy in Colombia manifests these issues and demonstrates the increasingly dangerous mining technologies that are used to explore mineral deposits without regard for who is harmed.

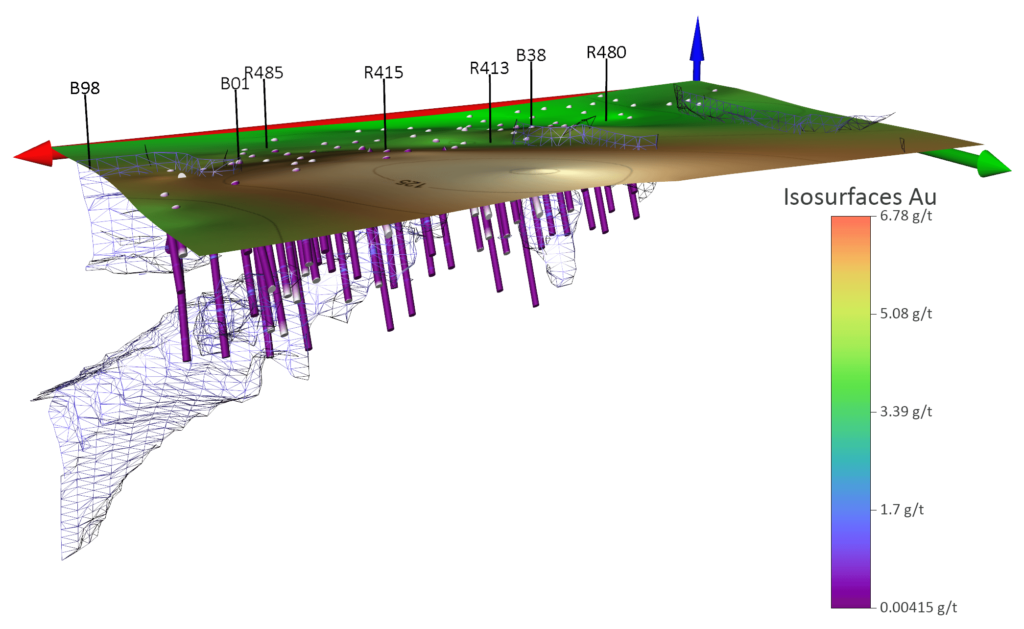

Subsurface resource exploration is an increasingly viable mode of retrieving mass amounts of minerals for the large-scale production of precious metals. In the past, subsurface exploration was hindered by observational geologic maps that could only predict mineralogical patterns in the subsurface by observing an outcrop and then applying the laws of superposition and lateral continuity.

The Law of Superposition: In sedimentary rocks, the oldest rock layer is at the bottom of a rock unit and the younger layers ascend upwards.

The Law of Lateral Continuity: All rocks continue horizontally (laterally) unless disrupted by a geologic process such as faulting or erosion.

This meant that a geologist’s prediction of where to mine was solely dependent on the number of outcrops in the area and the accuracy of the geologic map. Technological advances such as seismic data, chemical analysis, and coring have expanded subsurface exploration to the point where only those with the newest technologies can find profitable mineral deposits in remote areas.

Example of subsurface drilling and mineral visualization

https://www.goldensoftware.com/solutions/use-case/map-subsurface-mineralization

The South African AngloGold Ashanti mining company discovered a gold deposit in the Colombian subsurface in 2006 using drilling technology that led to “extensive exploration drilling in 2007” (NSEnergy). The thorough exploration outlined the oval shape of the deposit and discovered the complex to be largely a diorite porphyry with gold occurring in common sulfide veins and silicates. The exact measurements led AngloGold to predict that the porphyry body contains 28.33 million ounces of gold, the largest deposit in Colombia.

However, the residents of Cajamarca, a nearby agricultural municipality, raised environmental justice objections to the sale of land for mining. Mine tailings, acidic water, and loss of their forest reserve were just a few of the reasons locals protested the mining operation. These issues were especially problematic because of the remote agricultural economy that could be destroyed by waste mining products. Even still, the Colombian government was eager to make a deal with AngloGold.

In response, the residents of Cajamarca used a recent Colombian law that allows local municipalities to hold a binding referendum where citizens can vote whether to continue resource extraction or to halt a project all together. Against government persuasion, 98% of Cajamarca’s residents voted to halt AngloGold’s mining, hence ending all gold mining operations in the municipality for the time being. The focus of the Colombian Federal government on protecting foreign interests compelled the head of the Environmental Committee in Defense of Life from Cajamarca, Renzo Alexandria Garcia, to state:

“It is unacceptable to expect to mutilate Colombian democracy under the pretext of protecting the foreign interests of mining companies.”

https://earthworks.org/blog/98-vote-colombias-la-colosa-mine/

Cajamarca residents protesting the AngloGold mine

Luckily, the Colombian voting laws led to a happy ending and mine closure for Cajamarca in 2017. But, the story illustrates how technological advances in all resource extraction puts poor remote communities at risk of exploitation all over the world. Since these technologies indiscriminately search for geologic deposits in remote areas, small communities and less populated areas are targeted by major corporations. Mining technologies search specifically for the most valuable area to extract without considering fewer valuable areas with minimal impacts.

These concepts not only apply to mining but can be seen in other extraction such as oil drilling, where the most profitable drill site might be in fundamentally risky areas such as the ocean or protected wildlife localities. No matter the area or technique, extraction equipment is erected to maximize resource collection, not to minimize harm.

Contrary to neoliberal values, places are more than just a resource. The people of Cajamarca and of other remote areas have deep emotional and cultural ties to their community and to the places they are trying to preserve. By viewing areas simply as resources, companies ignore these invaluable attributes and hence devalue the land to only what they can physically extract from it. New mining and extraction technologies completely ignore the intangible characteristics of a place, worsening the issue of devaluation which allows mining companies to unjustly take the land.

In conclusion, the mining and resource extraction industries should examine the dangers of exploring and exploiting the most valuable resource areas when they conflict with local communities. International law must regulate these corporations and force them to take a more holistic approach to mining, especially in remote areas.

Sources:

https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/mining-metals/about-mining/operating-mines