By Ethan Kalishman

Sometimes, it is hard to conjure positive ideas about St. Louis, Missouri – that is, beyond the fact that both I and Budweiser were created there. Jokes aside, St. Louis has a rich, yet complex history that has continually generated reverberations around the world, from the Dredd Scott court decision to Ferguson’s Police Shooting of Michael Brown and 2020 BLM protests. Naturally, the media and nation may perceive the city as a haven for crime, murder, and racial strife. MSNBC, for example, has published an article as recent as a week ago saying that “With an alarming 69.4 percent murder rate, St. Louis holds the unenviable position as the most dangerous city in the United States. Countless residents report urban decay, badly-damaged roads, drug use, and an unhoused population spiraling out of control as to why murder rates are so high. To make matters worse, local officials seemingly have no idea how to fix things.” However, I believe that the challenges that establish St. Louis as a prime case study of policy failure create a deep bond among St. Louisans. After all, the St. Louis Cardinals finished second in highest attendance for the MLB in 2022, drawing 3.32 million fans. Somehow, I am just as proud to be a product of Missouri as I am also weary of our faults. I hope to demonstrate this sense of resiliency by depicting the long story of the Delmar Divide.

In class, we read from Richard Rothstein’s story of St. Louis, which powerfully depicted St. Louis and Ferguson as a prime subject of the area’s color of law and racial discrimination. A lot of his claims rang true with my own life experiences. For example, Rothstein described the suburbs I have grown up in that I see myself as segregated because of redlining, housing covenants, and other localized racial restrictions. However, Rothstein did not capture every story of St. Louis’ difficult and harmful discrimination and I think it is essential to extend his study onto Delmar Boulevard’s disparity to better understand the city’s oppressive urban policy.

The Delmar Divide is a term labeled for Delmar Boulevard’s stark socioeconomic and racial division between either side of the major east-west street in St. Louis. As the BBC reports, to the North of Delmar, the median home value is $73,000, the median household income is $18,000, 10% of the population has a bachelor’s degree, and 98% of the population is Black. These facts are contrasted by the South of Delmar, where the median home value is $335,000, the median household income is $50,000, 70% of the population has a bachelor’s degree, and 73% of the population is white. As a result, schools in the northern neighborhoods receive 30% less funding per student compared to those in the south, leading to disparities in academic performance. This segregation can be further reflected in cancer outcomes, as communities north of Delmar hold higher rates of breast cancer. In fact, Black women north of Delmar are more likely to be diagnosed with later stages of breast cancer with a mortality rate 10% higher than the total population, since these women are more likely to delay diagnosis and treatment due to cost. While there are many other facts of disparity, it thus should be clear that this divide powerfully stands.

Delmar’s gap of equality is historically rooted in redlining practices, which limited access to loans and resources for Black communities. This divide importantly did not happen overnight. As Darian Wigfall, activist, artist, and filmmaker says on a Now This segment “the racial divide here is a hangover from the history we have.” Next City Magazine also describes the Delmar Divide as an intentional phenomenon: “In the early 20th century,” it writes, “as former enslaved persons and their descendants began to escape the Jim Crow south during the Great Migration, the white-controlled St. Louis real estate industry employed a system of racial covenants and steering to drive the city’s growing black population to neighborhoods north of Delmar, while driving white families to the south.” Later, between 1934 and 1962, the FHA insured $120 billion in home mortgages, with 98% going to white borrowers. As a result, nonwhite populations couldn’t make necessary repairs to their homes, and the next generation of buyers were also precluded from taking over from predecessors. While the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, which ended explicit redlining, it was too late for homes north of Delmar. After decades of being denied the capital to keep homes livable, homeowners simply walked away to suburban life. Illustrating it is the fact that St. Louis had a peak population of nearly 860,000 in the 1950s and today it’s just 319,000. It’s a steeper decline than any of the former industrial powerhouses known as “Legacy Cities.” That’s one reason why when I and my peers say I am from St. Louis, we mean that we are from St. Louis County, not St. Louis City. I myself am a product of the city’s redlining, living in a white suburb. And yet, that does not mean the region’s fate is sealed or doomed.

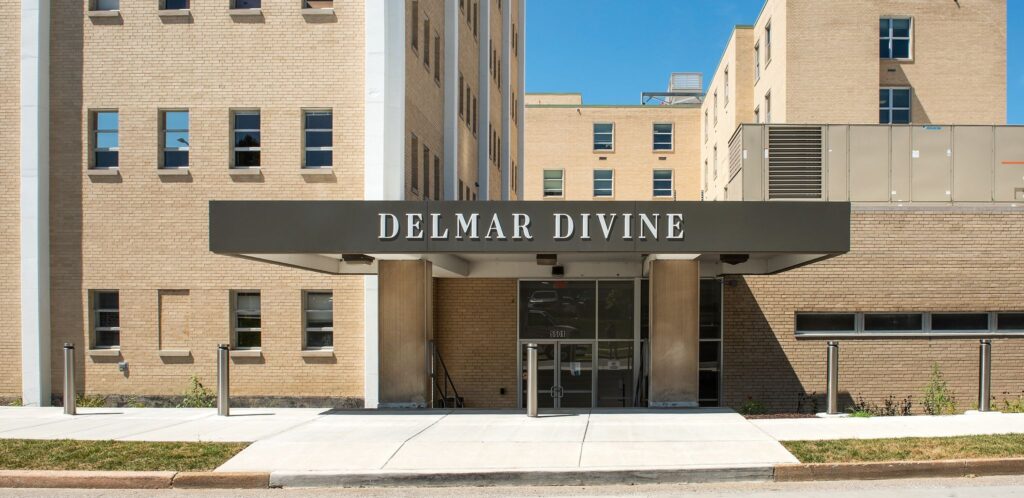

Maxine Clark, affectionately known as the founder of Build-a-Bear Workshop, derived an idea to bridge both sides of Delmar with a $100 million rehabilitation of St. Luke’s Hospital. Calling her project “Delmar DivINE,” she aimed to “redefine the West End neighborhood, beginning to replace decades of neglect with innovation, development and sustainability.” Consisting of a 150-unit, 8-story apartment building, the 2021 mixed-use project includes affordable modern apartments, offices, a café and a nonprofit collaborative aimed to support over 20 local agencies combatting injustice. Delmar DivINE’s funding comes from a public-private partnership that ironically includes FHA insurance on the loan, but also new market and historic tax credits, as well as donations toward the nonprofit collaborative. Of course, the facility is not an end-all-be-all solution to the horrors of the Delmar Divide, but it is a powerful marker of admission of the issue surrounding the Delmar Divide and better yet, a positive force that will resist the power of the current divide. Delmar DivINE shows that as much as harmful policy has shaped horrible inequalities, our cities are not beyond hope. We can at least begin to reverse these situations with collective action.