by Rafael Coutinho Padua

Growing up in Rio de Janeiro, the Cruzada São Sebastião always intrigued me. It is a yellow and red housing project situated at the intersection of the two most affluent neighborhoods in the city – Leblon and Ipanema. The centrally planned modernist buildings are in a much worse condition than the country clubs and shopping malls adjacent to it. In an attempt to understand the history behind this urban planning wildcard and whether it was a successful project, I will explain and then analyze the history of the community, while also showing how drastic government changes in place result in negative psychological effects in the populace.

The Cruzada São Sebastião is between Leblon (top right), Ipanema (top left). Below the buildings you can see Paissandu Atlético Clube, a traditionally British country club

Our story begins about 10 minutes away from Cruzada, in the extinguished favela of Praia do Pinto. This settlement was home to about 20,000 people, in the upscale neighborhood of Lagoa. Perhaps because of its strategic location in the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, this favela attracted government planners to begin their plan to defavelize the city. As much as the intentions behind the project may have been good, it will become clear that there are downsides. I attribute the negative side of this change to two predominant factors – the nature of drastic and centralized changes in urban planning and the poor governance of the Military Dictatorship in Brazil, which was in its early years when the process of defavelization started.

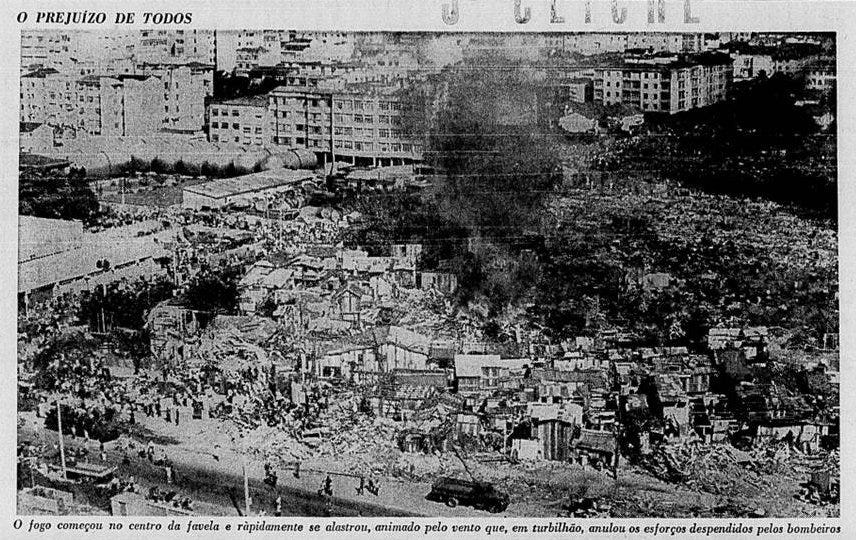

The Military Regime in Brazil, like that of many of its South American neighbors, was a violent one. The Praia do Pinto community was a clear victim of this. It is widely accepted that the favela was set on fire by the government in an effort to accelerate the process of the community’s relocation to Cruzada. Because of the aggressive nature of this change and the lack of checks and balances typical in a Military dictatorship, not everyone was granted housing and those who did still struggled to adapt.

This image shows the fire in Praia do Pinto. The caption says that the wind nullified the Firefighter’s efforts to reduce the fire.

The ‘luckiest’ inhabitants of Praia do Pinto were given an apartment in Cruzada. However, they still had to adapt to their new lives, now with toilets, sinks and a sewage system at their disposal instead of the collective tap and the porta-potty that most inhabitants were used to. In a TV interview, Maria Regina dos Santos, one of the many people who were forced into a new apartment, remembers her family struggles to learn how to use toilets and the sink, highlighting the friction she witnessed when relocating (WikiFavelas). Júlio César, a soccer player who also was forced into the Cruzada, argued that he was negatively affected by his relocation in a different interview (docsluciodecastro). While crying, he claims that moving into Cruzada was one of the many instances where life punched him in the face (docsluciodecastro).

Both of these examples show that humans can struggle with sudden changes caused by central government planning, and this causes negative psychological effects. Both Júlio César and Maria were victims of Root Shock, defined as a traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of one’s emotional ecosystem (Fullilove). If the experiences of people who were forced to move into Cruzada were sufficient in showing the injustices caused by the defavelization plan, the experience of those relocated to distant favelas shifts the concept of environmental injustice up a gear. An example of that is the experience of Tony Barro, a photographer who was forced from Praia do Pinto to Cidade de Deus. Tony explains that he was “almost thrown” from one favela to another, and that Cidade de Deus felt to him like “another world” (TV Brasil) Cidade de Deus, the favela portrayed in the film City of God, was isolated from the rest of the city, scarce in resources, and extremely violent.

Child gets hair cut in the recently built Cidade de Deus.

As we can see, the Cruzada was the product of an unsuccessful and violent government effort to get rid of favelas. While some may argue that the move from Praia do Pinto to the modernist project of Cruzada was an infrastructural ‘upgrade,’ it is hard to deny the negative psychological effects of this change. Tony and Maria likely share their experiences with other victims of defavelization, a process where violent governance met the unpleasant frictions of change and created another outbreak of Root Shock in the Southern Hemisphere.

Works Cited:

docsluciodecastro. “Cruzada São Sebastião – Lúcio de Castro – Parte 2 de 5.” YouTube video, [11:26. December 19, 2011”. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tb2Q_8opCy8&t=575s .

Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, And What We Can Do About It. NYU Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt21pxmmc.

TV Brasil. “Remoção da Favela da Praia do Pinto (1/4) – De Lá Pra Cá – 11/05/2009.” YouTube video, 10:02. June 2, 2009. Accessed October 17, 2023.[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JwWcfPC6isw].

WikiFavelas. “Favela Cruzada São Sebastião.” Accessed October 17, 2023. https://wikifavelas.com.br/index.php/Favela_Cruzada_S%C3%A3o_Sebasti%C3%A3o.

I truly enjoyed your blog post and your unique perspective, especially the comparison you outlined between defavelization and Fullilove’s concept of root shock.

Another comparison that came to mind when reading was the similarities between defavelization and the urban renewal program in the United States. While I would argue that urban renewal was more explicitly racially motivated than defavelization in Brazil, both cases were ambitious urban projects with the aim of transforming impoverished or “blighted” areas. Further, the outcomes of both programs included adverse psychological effects, such as root shock, on the affected communities. Also, while defavelization was spearheaded by a military dictatorship, and although urban renewal was carried out by a democratic government, the groups targeted by both policies lacked any substantial political sway in determining their fate. Further, you mention that the incentives behind the Cruzada São Sebastião project may have been good. With American urban renewal, it appears that economic incentives were the primary motivators. In Brazil, I wonder if defavelization was more prompted because of its perceived economic or social benefits.

I loved learning about how urban planning can have similar impacts to older, low income communities in Rio de Janeiro, which was something I hadn’t known much about before. I think it’s a really interesting case to consider when thinking about right to place and informal (non-legally documented) land ownership–these people had very low resources formally, but if they actually had the rights to the land they occupied they would have had much more social capital. You made a great case against defavelization!!