Filter restaurants by “Italian” on Google Maps, and seventeen results pop up between Clinton and Utica. While offering many of the same staple dishes, these establishments range vastly, from homestyle joints like the Spaghetti Kettle to sleek, modern spots like Nostro. While a few locations on the list are chains, the majority are independently owned and locally operated.

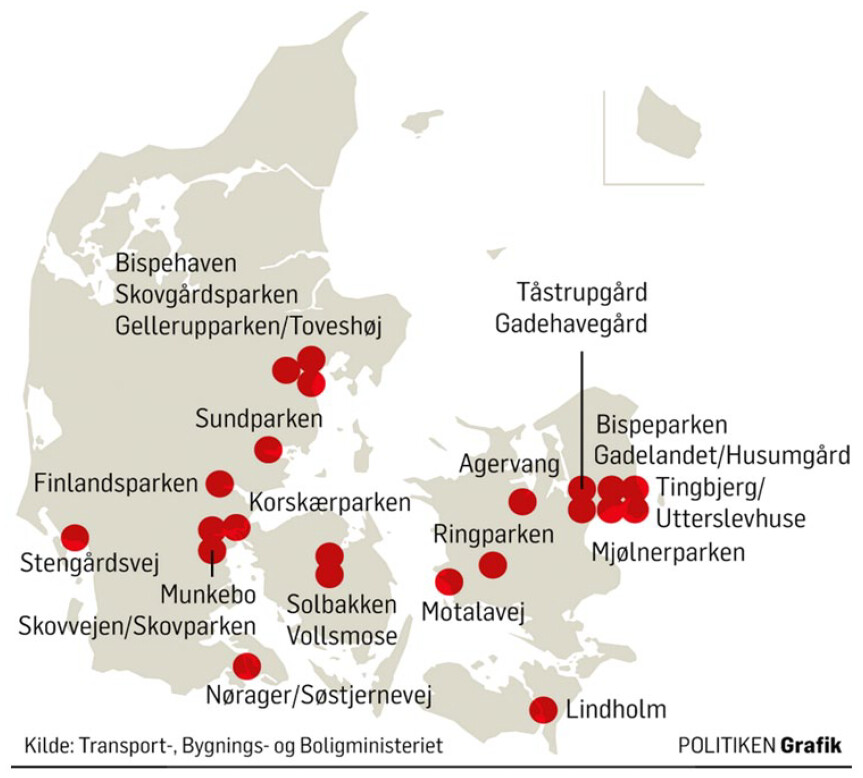

To call these restaurants “Italian,” however, would be a misnomer. Most of the restaurants eschew this simplified descriptor, identifying instead as “Italian-American,” a veritable cuisine in its own right. Utica’s iconic dishes, Utica greens and chicken riggies, are prime examples of this hybridized but well-established cuisine, with roots tracing back to the wave of Italian immigration in the late nineteenth century. The prevalence of Italian-American cuisine in the Central New York area is as much a story about adaptation and acceptance as it is about ‘old-world’ ingredients or expertise, providing valuable insight into both the history and trajectory of Utica-area immigration.

Chicken riggies from Chesterfield’s Tavolo, the Utica restaurant laying claim to the famous area dish (Chesterfield’s Tavolo).

Around the turn of the century, Italians made up a higher percentage of the Utica population than in New York City, Chicago, or Philadelphia, powering factories and construction in the rapidly industrializing city. Like Italian immigrants across the country, Utica-area transplants adapted many of their food habits to their new living contexts, growing produce in small backyard gardens and fermenting wine in basement cellars. The U.S. Food Administration’s attempts at forced culinary assimilation, often centered around arguments regarding nutrition and hygiene, largely went unheeded. As one public health reformer wrote, “people of this nationality… cling to their native dietary habits with extraordinary persistence.” With Italian immigrant communities resisting Americanization, the FA’s campaigns mainly served to entrench xenophobia among native-born populations.

As with the initial ostracization of Italian cuisine, its eventual acceptance by American society has decidedly political roots. When Italy joined the U.S. as an ally in World War One, Italian food was suddenly celebrated as a patriotic addition to the American diet. “Ravioli, favorite dish of our Italian ally, should be served on every American table,” read one 1918 Good Housekeeping article. Beyond serving as a symbol of wartime solidarity, Italian food culture was embraced for its thrift and reliance on vegetables, crucial culinary characteristics in times of rationing. As the 1918 Good Housekeeping article explained, “meatless days have no terror for our Italian friends.” American acceptance of Italian cooking surged again during the Great Depression, when stretching meat and preventing waste again became a necessity.

While America warmed up to legume soups, ravioli with tomato sauce, and the people who made them, stateside Italian cuisine was undergoing its own transformation. Most Italians who came to the U.S. during the main wave of immigration came from the southern regions where families reserved pasta, dairy, and meat for special occasions. In the prosperity of post-war America, recent Italian immigrants celebrated their new societal and economic status by creating hybrid dishes with these “high-status” ingredients. National favorites like spaghetti and meatballs and Utica classics like Utica greens and chicken riggies permeated the American culinary lexicon as a cuisine entirely distinct from that found back on the peninsula. Despite the challenges, Italian-American cuisine became a mainstay and point of pride in American food culture from household dinner tables to restaurants, including those in Utica and its environs.

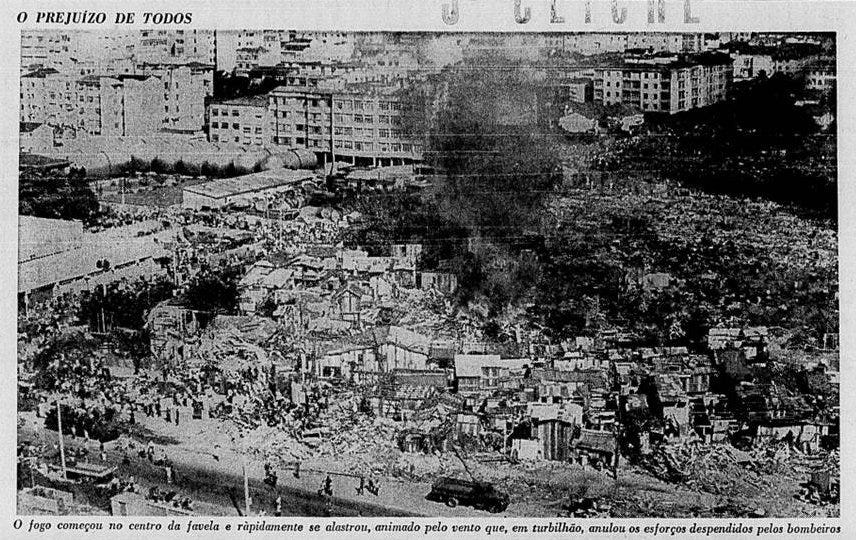

Southern Italian traditions live on through Saint Mary of Mount Carmel Church and Santa Rosalia’s Feast, first celebrated in 1915 (Daily Sentinel).

Over one hundred years after mass Italian settlement, immigration remains an integral part of Utica’s story. As Central New York industry collapsed and Utica’s population precipitously declined through the end of the twenty-first century, Bosnian refugees strengthened the city. In 2005, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees focused an issue of its magazine on Utica, calling it, “The Town That Loves Refugees.” In 2017, twenty-five percent of Utica’s population was estimated to be made up of refugees and their children. Later immigration from Vietnam and Russia, and more recently from Burma and Somalia, has continued to shape Utica’s revitalization—and culinary landscape.

Mersiha Omeragic opened Yummilicious after coming to Utica in 1994 as a Bosnian refugee. Bosnian bean soup sits adjacent to chicken riggies on the diverse and popular cafe menu (Utica-Observer Dispatch).

The immigrant experience in Utica vividly illustrates the ongoing process of leaving one home and establishing another, with food playing a pivotal role in this journey. The prevalence of Italian-American restaurants in Utica stands as a testament to a long history of resistance, adaptation, and eventual integration. Hybrid cuisines capture extended narratives of cultural negotiation, where food symbolizes cultural preservation, adaptation, and acceptance. This process of place-making in Utica continues with the arrival of new immigrant communities. Take the example of Yummilicious, a Bosnian-owned restaurant offering a range from waffles to meza, which is carving out a place in Utica’s culinary scene alongside established favorites like Delmonico’s and Chesterfield. The growing popularity of these more recently arrived immigrant cuisines suggests a more inclusive reception for new arrivals. This hopeful trajectory suggests that Utica’s culinary landscape will increasingly reflect the rich tapestry of its diverse community, continuously evolving as new flavors and traditions become recognized as integral to the city’s identity.

Guttman, Naomi, and Roberta l. Krueger. “Utica Greens: Central New York’s Italian-American Specialty.” Gastronomica 9, no. 3 (August, 2009): 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2009.9.3.63.

Hartman, Susan. “How Utica Became a City Where Refugees Came to Rebuild.” Literary Hub, July 9, 2022. https://lithub.com/how-utica-became-a-city-where-refugees-came-to-rebuild/.

Haverford College. “Exploring the ‘Urban Colonies’ of Utica,” September 16, 2010. https://www.haverford.edu/college-communications/news/exploring-urban-colonies-utica.

Levenstein, Harvey. “The American Response to Italian Food, 1880–1930.” Food and Foodways 1, no. 1–2 (January 1, 1985): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.1985.9961875.

Sullivan Borrelli, Katie, and Tracy Schuhmacher. “Utica’s Refugees Bring Transformation to Upstate NY.” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, January 10, 2022. https://www.democratandchronicle.com/in-depth/news/2022/01/10/uticas-refugees-upstate-ny-transformation/8765746002/.

Utica: The Last Refuge. “Utica History.” Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.lastrefugedocumentary.com/learn-more/history.

Utica University. “Ethnic Heritage Studies Center.” Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.utica.edu/directory/ethnic-heritage-studies-center.