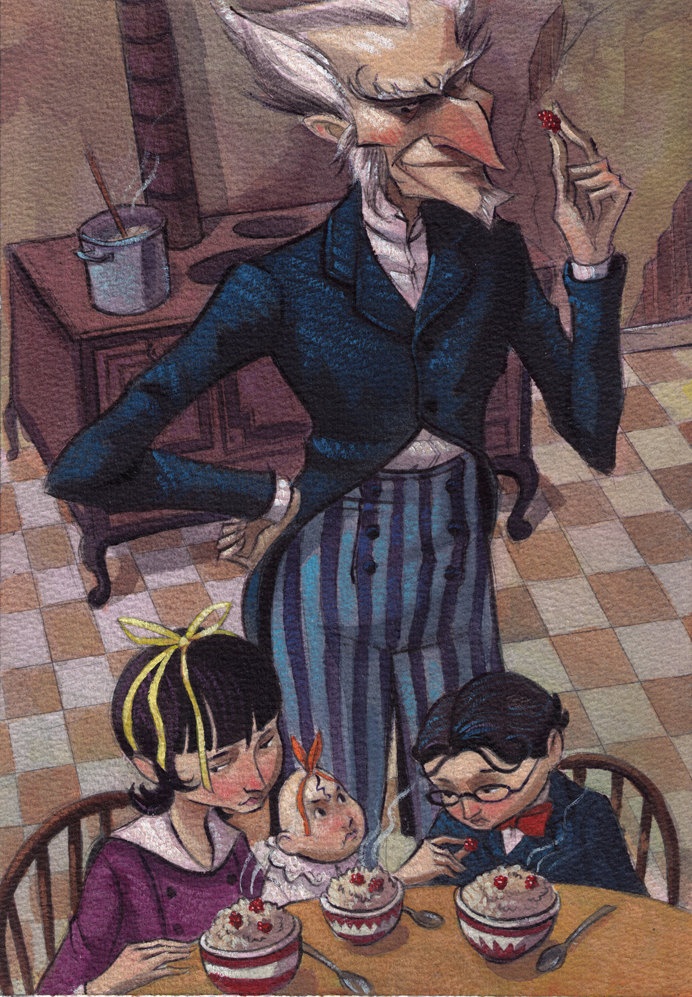

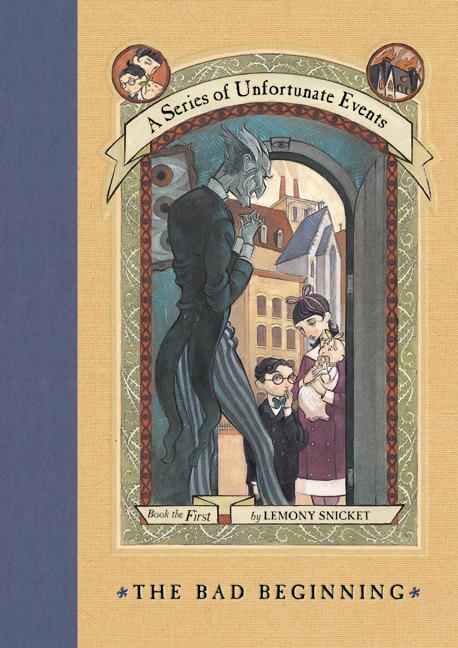

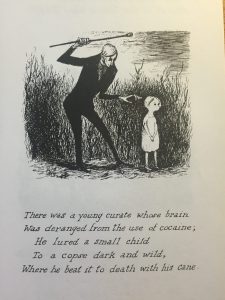

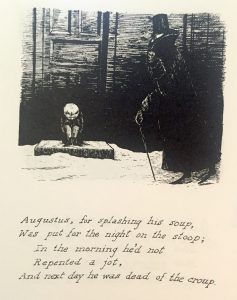

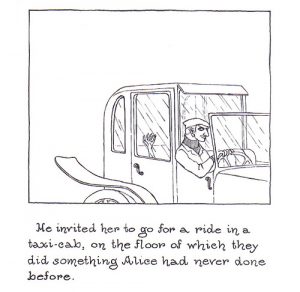

Amphigory, by Edward Gorey, was one of the most confusing and therefore intriguing works we have looked at all year. Due to the friendly and childish nature of the characters within his book, one would assume the stories the images describe to be more appropriate for a younger audience, but of course the stories contain mature content. The juxtaposition between Gorey’s child-friendly artistic style and his stories’ content is quite obvious and got me to wonder, what was Gorey’s view of his own artwork? I remembered a quote mentioned in class about how Gorey did not consider his work to be for children, so I looked the quote up and this is what I found:

“If you’re doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because there’d be no point. I’m trying to think if there’s sunny nonsense. Sunny, funny nonsense for children — oh, how boring, boring, boring. As Schubert said, there is no happy music. And that’s true, there really isn’t. And there’s probably no happy nonsense, either.” Read more at: http://www.azquotes.com/quote/695116

This Gorey quote seems to perfectly summarize the way Gorey categorizes his work, however, I extremely disagree with Gorey in his evaluation. I think Gorey truly believed and wanted to convince people that his work was not for children, and that sad things did happen in his stories. Having said that, why would one read a book full of his stories if not to receive some sort of benefit or satisfaction? The characters are child-friendly, (actually remind me of characters in Roald Dahl books), why not make the characters in the stories more sinister in nature, to match the events that take place in the story? The nature of the cartoon drawings and the nonsensical nature of his stories make them entertaining and I would argue, have the ability to instill happiness in the viewer. While they may not be child-friendly stories, the stories are happy in the sense that they cause the audience to laugh or smile when reading them.