As I read the excerpts about Achilles’ shield, I couldn’t help but read it as a sort of textual meta-image. The art described on the shield seemed to have some sense of self-awareness. Though the section of the shield (many of us placed this on the outer edges) describing the sun, moon, earth, stars, and gods did not really seem self-referential, the scenes involving people and the two cities did. While one city celebrates a marriage, the other is in a state of war, defending itself from outside attackers. Though no shield is directly referenced in this battle, it is not at all difficult to imagine the shield on which these images are crafted being used in a battle such as this, perhaps even this exact battle. It seems to subtly acknowledge itself as a shield through the art on its surface. Additionally, it is possible to interpret the images as representations of what the shield was built to protect. Since this shield was given to Achilles, a warrior who was not particularly hell-bent on mindless destruction and war, it is possible that the images suggest that the shield was made to protect humanity and all the other elements that the art encompasses. In that case, the description of the shield would be a textual meta-image because the art on the shield fully acknowledges itself.

Book of Hours: Calendars

Books of Hours typically begin with a series of illustrated calendars that delineate the holy days and celebrations contained within specific months. This information manifests itself as a body of text within a frame that is itself surrounded by elaborate illustration. The accompanying illustrations are all connected by a theme: the pictures show feudal life in its various walks, usually pertaining to the season that the month falls within.

There is a historical consensus that these devotional books belonged solely to those who could afford them: namely, manorial lords and members of the aristocracy. It is no surprise, then, that many of the illustrations besides the calendars depict lords or ladies in luxurious situations. One such illustration contains a lord sitting in a great hall, warming himself in front of a hearth while a meal is laid out behind him by a serving girl of negligible importance. Another shows a well manicured lawn being traversed by a stately-looking couple in noble clothing, while other couples of similar import enjoy music or lounge by the waterfront.

What is peculiar, in light of the knowledge that these books belonged to the wealthy few, is the emphasis that the artwork places on the working men and women of the estate. An inordinate amount of the illustrations depict vassals attending to chores, such as tilling fields, reaping crops, slaughtering animals, sweeping floors, or serving food. I am curious as to whether this seemingly deliberate featuring of serf life is intended as celebratory – a lord taking pride in his vassals’ work – or sadistic. The latter conjures the image of a smug noble reveling in the grueling work of those indentured to him, while the former paints a much nicer picture of the medieval boss-employee relationship.

Illuminated Manuscripts = self-referential?

Is the Bible a metapicture? After studying religious texts during our unit on illuminated manuscripts, I began to question the importance of the Written. The manuscripts we’ve studied and The Book of Kells demonstrate a great reverence for the written, the pictoral, the literary sign; these entities garner more respect in ancient times than I think we attribute to them today. When we consider early Western images, they seem nearly inseparable from the divine. In the case of illuminated manuscripts, I think these religious texts remain sacred because they seem to tangibly demonstrate the power of God and man’s function within God’s plan.

If we believe the Bible and scriptures, humans are God’s greatest work of art. God is the ultimate artist/writer, and supposedly created humans to carry out his teachings and plan. The creation of a book is a similar endeavour, but on a human scale. Humans create the intricate pictures found in sacred manuscripts express the ‘message’ of the passages they accompany, lending support to the words of God in a parallel process of creation. The miniatures adorn pages that narrate the very origin of (holy) design, of intentional artistic rendering, the creative endeavours of the grand immortal artist.

The human, the being most similar to God, aspires to imitate its creator. Following this logic, we (humans) are art (the creation of God), that creates art (illuminated books), that creates the creator (the sacred books/miniatures disperse and make real the presence of God for the laymen), who creates art (back to the creation of man). The illuminated manuscripts, then, are entities that call into question and express the very nature of humankind: are we, in fact, self-referential images of God?

Was the popularity of illuminated manuscripts due to their self-referential properties? Probably not, but it’s something to think about.

Hope these random philosophical musings make sense in some way to other people!

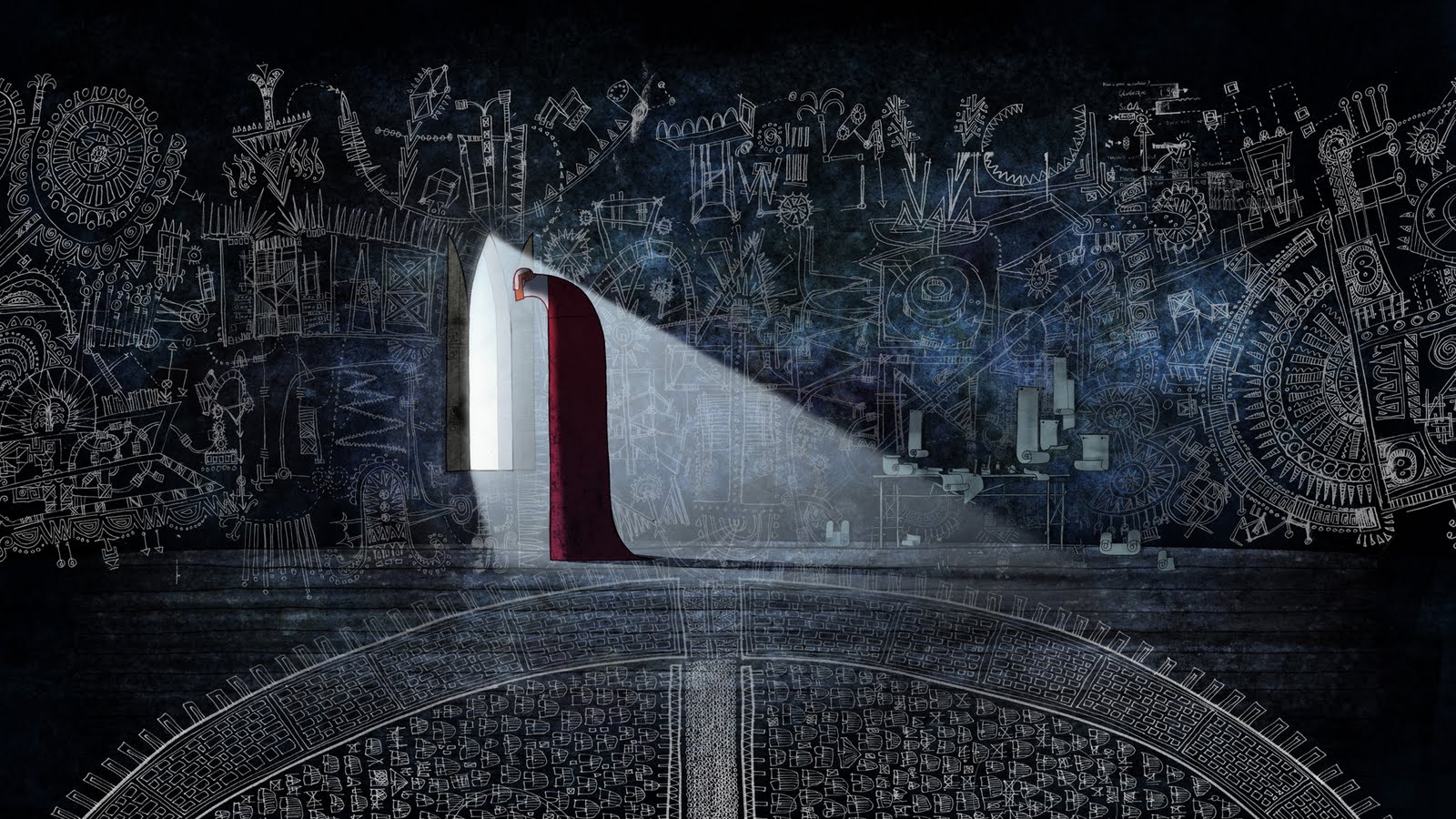

Illumination and the Secret of Kells

In the course of the past few weeks I have been struck by the incredible beauty and intricacy of the illuminated manuscripts. Though they are often directly intended to convey part of the written narrative, it seems clear that they go beyond. After all, most of the patrons (The few that could afford such works) who commissioned illuminated texts could not read. They needed to inspire awe and religious feelings without words. I did not realize before how important such a task was nor the dedication required to execute.

The Secret of Kells helped get across not only the amount of detail but also the intricacy of the designs. They were intricate but always enhanced the story in surprising ways. The scene with three panels of Aedan and Brenden walking and growing older was one of my favorites. The film also helped illustrate the environment these works were often created in as monasteries, especially in England, were preferred targets for viking raids. The message in the film seemed to be that people should not be so consumed by fear that they forget to keep making beautiful things.

The Secret of Kells and Illuminated Manuscripts

While watching The Secret of Kells, I considered the juxtaposition of making a movie about ancient times and manuscripts through modern digital animation. The painstaking process of creating an illuminated manuscript and the creation of a digitally animated movie seem not to have very much in common. Illuminated manuscripts must go through many different steps and many different people with specific skills, like scribes and illuminators, to become a finished product. The process is long and arduous. While many people must collaborate to create an animated film, the actual process of animation itself can be done quickly and easily by pretty much anyone who has access to a computer. Anyone could potentially make their own animation today, though in ancient times it was nearly impossible to make your own illuminated manuscript from start to finish.

Though these two creative processes seem very different, the animated film The Secret of Kells combines them in an interesting and artful way. The animation style is reminiscent of the illuminated miniatures in ancient manuscripts. Just as all boarders and margins in illuminated manuscripts are covered in ornately detailed drawings, so is nearly every scene of the movie. I don’t think there is a single shot where the screen is not completely filled in with unique ornamentation. The characters are two-dimensional, just as the appear on the pages of manuscripts. Similarly, all the characters move within the same plane, which eliminates spatial perspective the same way looking at images on a piece of parchment would.

I found the film The Secret of Kells a very interesting and visually beautiful combination of the old and new styles of illustration and animation.

Illumination and Animation

I thought Secret of the Kells was absolutely beautiful. What I most appreciated was the effort to echo the laborious art of illumination in the animation. The animators clearly took elements from traditional celtic art into account, and the subtle influences made for a bold and clean feature that was a pleasure to watch. The example that comes immediately to mind is the climactic battle between Brendan and the Crom Cruach, wherein the body of Crom Cruach forms a pattern similar to those found on the borders of Irish illuminated manuscripts. To me, it felt reminiscent of Disney’s Hercules, or even Mulan, but with a more direct and explicit intent (and perhaps a little less appropriation).

More than that, however, it also takes the elements of traditional illumination, both stylistically and in spirit. The attention to detail, the juxtaposition of light and dark, and the sense of mystery, history, and dedication inherent in the animation all echo the subject of the film–illumination.

Achilles’ Impossible Shield (Reposted)

Achilles’ shield is an impossible object, which makes the ekphrastic process attached to it all the more crucial. It carries not only the narrative of Greek history but the mythologization of that history as well, as the inclusion of figures such as Ares and Athena demonstrates. Yet the shield itself is embedded in that complex interweaving of myth and history mythology, albeit on a meta-level. It carries the story of which it is part. Readers understand that the position the shield occupies makes it an impossible object moreso than the complex physicality. Thus what is left to the reader is a description of depiction, a series of words, a chunk of text that serves as the ‘voice’ of an object that has no physical being beyond its mythical role. As it carries the history of Greece, the shield is meant to be understood as a physical object, but at the same time, as a figure with a role within the meta-myth, the shield is obviously composed of words on a page and not of carved metal.

Ekphrasically, then, the section of text devoted to Achilles’ shield is both descriptive and depictive, and it is difficult to say whether one or the other takes dominance. In a sense, there is nothing to depict; the shield is fictional, a construct. Supposedly a physical object is being described, but in the absence of that object, the words must be equal to the weight of the shield. This would be a typical ekphrastic approach. However, the object cannot truly be said to be absent from the description because the description comprised the object in the first place. What we are left with is an object that is both physically impossible and physically necessary on different textual levels and thus can perhaps only be a textual object, practically speaking. And yet the scenes attributed to the shield are so complex that we might also require the aid of an illustration to understand what is being described- thus the shield is given a kind of second-order physicality. Achilles’ shield thus traverses the narrative and the illustrative, the textual and the visual, in a way that requires readers to recognize the overlap between these categories.

A metapicture is a tool for looking at other pictures

Mitchel argues that a metapicture is a self-referential picture and I find that compelling because his discussion on how this dimensionality helps us interpret other pictures is quite insightful and significant to the way artists create images and the way critics look at these images. This made me think of criticism theory of pictures, we should probably search for indications of multiplicity through which the image attempts or directs us in the direction of creating a certain discussion about it. Therefore, as argued by Mitchel, the visual depth that an artist provokes matters a lot, but this depth partially stems from intellectual roots, because if the artist is trying to create a representation of an idea and connecting this idea to a certain image then he is also incorporating his personal/cultural associations or views. So when we are looking at pictures we need to bear in mind the possible references to culture and the personal interaction of the artist with that culture. To me, this adds a solid conceptual element to the way I look at paintings and sculptures (forms of art I usually like to understand).

Purpose of Manuscripts

The intriguing aspect about many of these illuminated manuscripts is their lack of utility. They were paid for by people who couldn’t read, written by monks who could read, and handed to patrons who relied on pictures to understand the print. Interestingly, one could only understand the picture if at one point, orally, they received the information necessary to decipher the imagery. Hence, despite being a visual culture of some sort, the majority of users of the manuscripts still required the older practice or oral communication.

In fact, when reading about the evolution of illuminated script in the Renaissance, I could only think of the art theories of John Berger. In his Ways of Seeing he discusses that the way we look at the art shouldn’t be just on its formal or thematic level. The picture of St. Augustine provided in the PDF demonstrates the early development of depth and volume (although rather cluttered and rationally incorrect) is fascinating on the formal level to see illuminated manuscripts develop as painting technics developed as well. Berger claims that the physical art and paint are simply a representation of societal peacocking by social standards. To look at the art for what the physical manifestation means – often the declaration of wealth and taste – is most likely the correct way to go about understanding the importance of illuminations. If it is useless in utilitarian way, it must have been a visual status symbol. The more gold, jewels, and detail the books held, despite what information they held, the more powerful the patron would appear. Thus reading the illuminated manuscript as tactile symbol of power decipherable by all those who lived within and could read the social structure and its cues.

The Secret of Kells

The Secret of Kells is probably one of my favorite films. The way that the story, the colors and the designs all reflect the book that is the subject matter. The art is gorgeous. Learning that it was indeed based on an actual illuminated manuscript was not surprising and added another wonderful layer onto the film. The direct subject matter of the film was about obtaining a magnifying glass in order to be able to complete the book. I have seen illuminated manuscripts in person before, but I never realized how small some of the most common ones are- and I never quite understood the importance of the oculus in the film. After looking at the Book of Hours in class and slides of the real Book of Kells, I understand how laborious, time-consuming, and carpal-tunnel-inducing illuminating actually is.