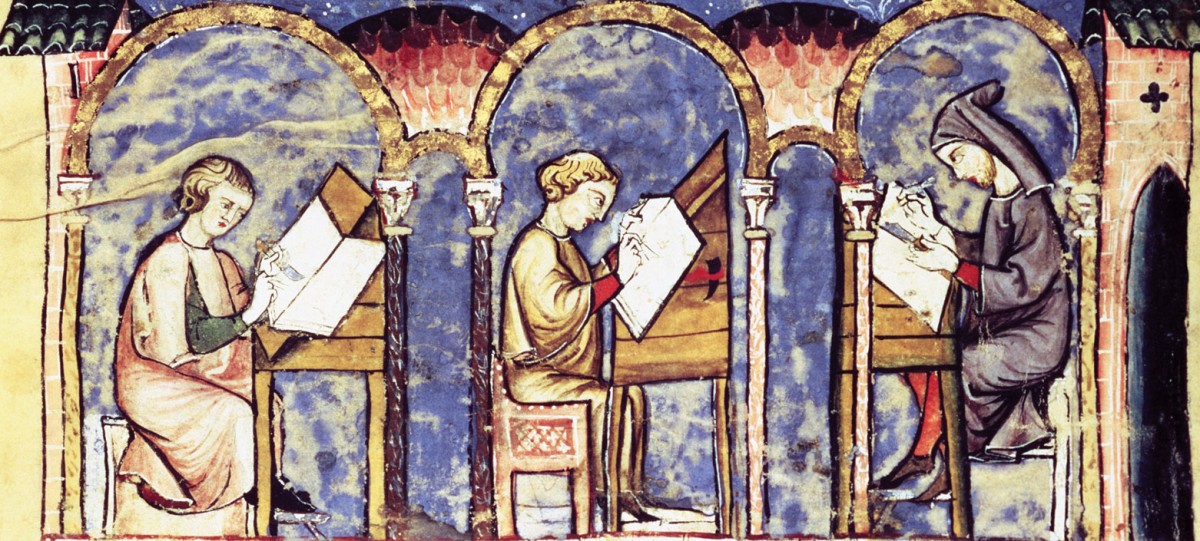

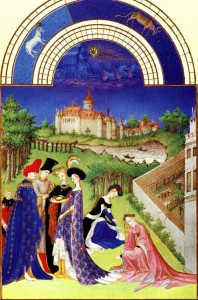

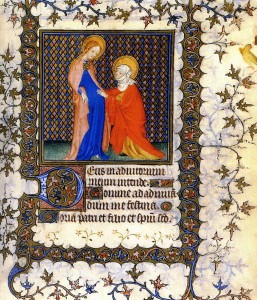

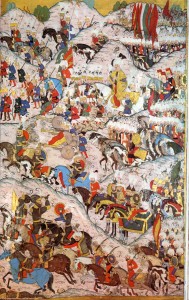

The Venetian manuscripts of the 16th century privileged individual style over the imitation of past artistic forms. It was an innovative philosophy that would trouble the Ottoman Empire, a culture whose miniaturists conformed to Islamic practices that foregrounded non-representational techniques, portraying, through ornamentation, not “a tree” but “its meaning”. To look upon a Persian manuscript was to look down from a beautiful minaret, to look through Allah’s eyes, to see earth from a great distance and, as such, only see whispers of it. Consequently, an artist who broke from such artistic traditions, allowing themselves to be influenced by renaissance aesthetics, was deemed sacrilegious.

Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red carves a murder mystery from a climate of such Islamic reluctance to Western, artistic influence. Miniaturists, who are secretly producing a book in the style of western manuscripts, are met with murderous contempt from their devout Islamic counterparts. And it is this disdain for prospective, individual style that prophesizes, through accidental allegory, contemporary art culture’s future.

With the advent of technology, contemporary culture has feasibly reverted to a reverence for conformity once more. Contemplate the ‘remix culture’, a recent art movement that encourages derivative works, works that support adherence to form. It could be argued that this has occurred from an over proliferation of Renaissance art’s desire for, aforementioned, individual style, meaning we have run out of new styles and ideas.

Everything has perhaps already been done.

This undoubtedly creates a ‘reverence’, ironically, for past masters in secular arts whose work we now create pastiches of. Even My Name is Red is a historical drama, a ‘remix of the past’, a pastiche of a culture that once was.

Considering, then, the reaction of devout Muslims to ‘heretical’ miniatures in the 16th century, I wonder how contemporary society, one that is largely secular, might react to future art movements that revolt against remix culture’s ‘pseudo-religious’ worshipping of preexisting aesthetics?

How will we react to artists’ desire for personal identity in their work?