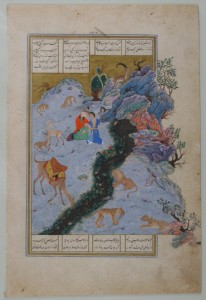

My Name is Red is a highly intertextual book, to the degree that some of Pamuk’s critics have accused him of plagiarism because of the extent to which his influences are traceable to other texts. Yet the idea of works of text being in relationship, perhaps even conversation, with one another is so central to the concept of My Name is Red that claims of plagiarism seem to ring hollow. The book is first of all conscious of itself as a book, a manipulable text-object. Furthermore, it is conscious of the fact that all the other books or manuscripts within the story are part of a historical continuation. Stories are encapsulated by stories, and because the old myths and histories are held in such high regard, all stories seem to lead into one another. The plagiarism issue also draws back to the question of style: one recognizes plagiarism by familiarity with the ‘original’ source and presumably part of that familiarity has to do with the style, the uniqueness, the memorability of that source. After all, the miniaturists in My Name is Red are all consciously trying to emulate, or more bluntly, copy the old masters, devoid of their own stylistic influences. But the old masters had to have been unique artistically in some regard; there was something that it was to be an old master, and that is what the mark of perfection has become. Of critical importance is the fact that emulation of the old traditions, whether in stories, texts, or miniatures, is an act of creating over what has already gone before.

A palimpsest is a manuscript page that has been cleared and written over, re-used as part of another document. In many ways, My Name is Red has the quality of a palimpsest. The murder of Elegant Effendi is covered up, yet the act of covering becomes part of the murderer’s new identity, new way of seeing. By ‘erasing’ one life, the murderer begins a new one and covers his transgression. To go further, the crux of the conflict in the text is the tension between old and new, a dialectic of ‘originality.’ The miniaturists struggle with the idea that breaking away from the old mode of depiction is sacrilegious and there is a constant veneration for the old methods and old masters. However, the act of copying or emulating is also a generative process and we see parts of the old being overwritten by what is new in the appropriated guise of the old. Enishte Effendi’s entire venture of creating a manuscript illuminated in the style of the Venetian painters is the most extreme example: his creation is something new because of the style but it doesn’t replace the old form of the illuminated manuscript, it re-uses and re-designs it. Pamuk’s intertextuality is another example of a palimpsest that functions on the meta-level. He too is grappling with the dialogue between old and new in the writing of My Name is Red. The constant reference to a kind of historical knowledge- old stories of lovers, old techniques of making dyes, perhaps even passages from old texts- is emulative and appropriative, the old histories serving as the raw material for new stories as the old manuscript pages did, the writing underneath just barely visible but still forever interlocked in conversation with what was written over it.