The forthcoming ‘scriptorium workshop’ sparked me this week to reflect upon the creative atmosphere of the miniaturist. A scriptorium, or simply “place for writing”, was situated, as we’ve discussed, in European monasteries. However, in the same way a contemporary artist or author might listen to music to gain inspiration, it is important to consider the miniaturist not in a vacuum but as privy to Gregorian chants carrying through the monastery walls.

As Orhan Pamuk so eloquent puts it: “painting is the silence of thought and the music of sight.” But was such ‘sight music’ influenced by music itself? Indeed, one need only consider both Baroque art and Baroque music or postmodern art and minimalist music to realize that art and music have traditionally evolved together, influencing one another. And perhaps the same can be said for illuminated manuscripts.

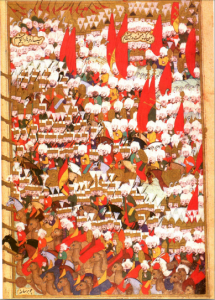

The Gregorian chant, or plainchant, was a monophonic (meaning there was no harmony) vocal performance and most certainly a staple of Western religious tradition, not eastern. Thus, it could be argued that Western monophonic performance prompted the singular representation of peoples rather than the traditionally Eastern lack of representation and multiplicity of peoples which may have occurred if the Gregorian chant was characterized instead by disorientating harmonies, or the representation of single harmonies lost amongst many!

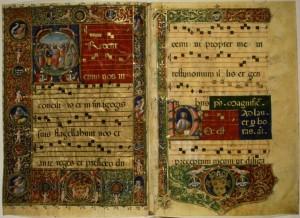

Now what if we were to consider music a language? Interestingly, the sheet music of Gregorian chants is one of the few representations of an ‘art form’, besides literature, that were ‘illuminated’.

And these illuminated pieces of sheet music are so beautiful and there are so many!

I simply wonder why, as a class, we are yet to treat music as a language, however indecipherable, and truly see the cross-modal relationship of art and music?

Why not let the illuminated manuscript sing?