This chapter is so meta (that’s so meta = new sitcom about psychic liberal arts students struggling with the everyday pitfalls of aesthetic discernment?), especially considering today’s modern printmaking industry. In fact, all of the chapters in this book narrated from the perspective of drawings have incredibly meta undertones.

Consider this: A drawing of a tree speaks to us from its position on a piece of parchment.

First level: A drawing bluntly postulates, criticizes, and yearns with human intensity. This drawing has, in other words, become its own autonomous entity, an organism with emotions and perspective.

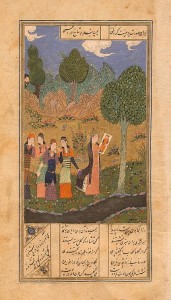

However, this tree “thanks Allah” (51) that he has not been drawn in the Frankish style, a style that allows viewers to “correctly select” one particular tree out of many. He is relieved to have been depicted in a uniform way, and is sad to have been ripped from the pages of a book–an action that calls attention to his individuality on display–but “secretly takes pride” (47) in the thought that men will prostrate themselves before his uniqueness.

Despite his embarrassment for wanting individuality, he has certainly achieved it. The tree is its own being, come to life through artistic expression. Our ability to listen to this internal struggle proves his autonomous, individual thought.

This could possibly be a comment the individual nature of all drawings. Despite the fact that several master illuminators worked to paint the Tree in a disjunct, interrupted manner (the way illuminators divide work in their professional workshops), and from memory, the Tree has achieved an individual flair. The divided composition of this drawing, meant to dissuade prideful illuminators from adding personal flair to their creations, has nevertheless produced an individual being. Does this comment on the impossibility of removing individuality from artistic expression? We know from Master Osman, for example, that even the best illuminators make mistakes, and that these mistakes become signatures (253).

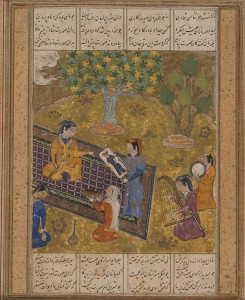

Second level: In many of my literature classes at Hamilton, we’ve discussed the voyeuristic qualities of book reading. The readers watch delightedly as a series of events unfold, completely invisible to the actors and judge the episodes of the plot privately. Observers enjoy this same voyeuristic perspective when viewing images, be it in art galleries, or at home on the sofa.

But this Tree, with all of its individuality, speculates about his own creation, observes his several different owners, and even speaks to the reader/viewer. He converses with us:

“My request is that you look at me and ask: “Were you perhaps meant to provide shade for Mejnun disguised as a shepherd as he visited Leyla in her tent?”” – p. 49

The tree watches us. Who is the reader, and who is the read? The tree also watches itself:

“I am a tree and I am quite lonely. I weep in the rain. […] At this moment, there are no other slender trees beside me, no seven-leaf steppe plants, no dark billowing rock formations which at times resemble Satan or a man and no coiling Chinese clouds. Just the ground, the sky, myself and the horizon.” – p. 47

Is the tree reading itself to produce this ekphrasis? When we describe ourselves, are we not describing the image of the self, and also performing ekphrasis? Are we the readers of our own books?

This level reinforces the individuality of the tree and calls into question our own role as readers.

Third level: The tree’s existence comments on the relationship between words and pictures.

The tree is a drawing, but expresses itself with words. We associate it with a picture (it is an image) His existence encompasses thought (words) and the pictoral realm. If this tree is an individual with human thoughts, does this quandry extend to our own existence? Are we all both drawing and text?

Fourth level: Although I’m uncertain, I assume that the parchments of the Ottoman empire (including the one on which the Tree is drawn) were made from animal skin. However, Orhan Pamuk most certainly did not expect My Name is Red to be printed on animal skin. That adds another interesting layer.

…technically this whole book is a tree. The drawing is a Tree, but what we hold in our hands is material from a living, breathing thing. No one tree is just like the other. Trees are unique, but also imperfect; “looking at a drawing of a tree is more pleasant than looking at a tree” the Tree notes on page 49. Therefore, each printed book will be slightly different from another copy of the same edition.

This has probably been the most frustrating level for me to ponder, and the following quote the most intriguing:

“I don’t want to be a real tree, I want to be its meaning.” (51)

What do you think it means? (inside or outside of the context of this post)