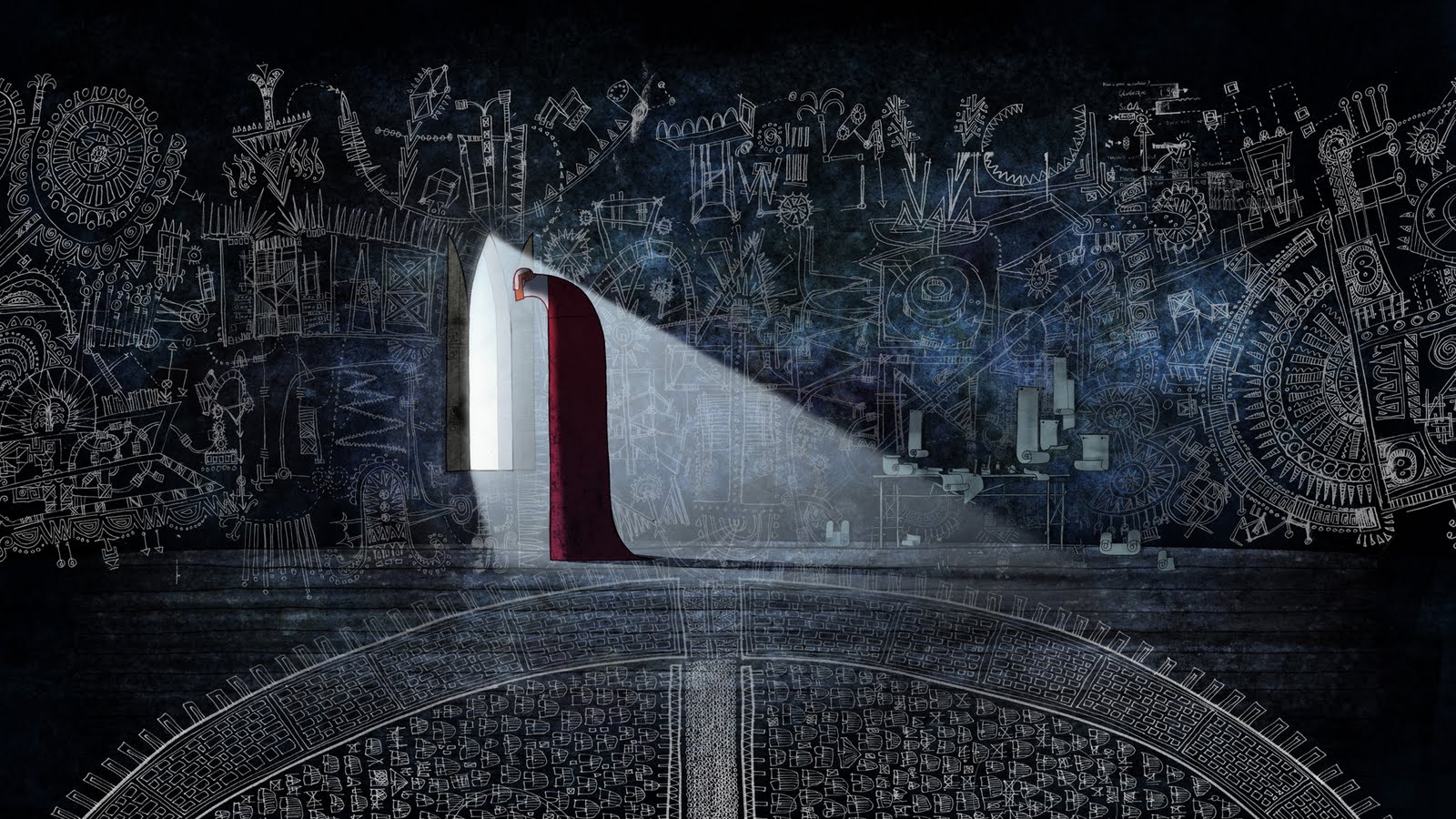

I really like the Selznick blurb on The Awakening interpreting the fantasy elements as culture shock–that as the narrator arrives in a new country, the architecture, writing, and animals are so wildly unfamiliar that they seem fantastical. It captures the loneliness and confusion inherent in any immigration experience, and Shaun Tan’s narrative is compelling and absolutely gorgeous.

Obviously, however, it does slightly romanticize a painful and complicated narrative. Introducing a magical element to explain homesickness and culture shock vaguely hints at colonialism and assimilation in a harmful melting-pot sort of way. But it’s definitely an interesting take on immigration, and it absolutely captures the sheer unfamiliarity of moving to a foreign country.